Hollister riot

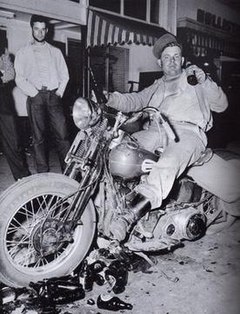

Eddie Davenport of Tulare, California on a motorcycle, with Gus Deserpa standing at left, outside 526 San Benito Street, Hollister, California, on July 4, 1947. Photo by San Francisco Chronicle's Barney Petersen.[1] | |

| Date | July 4, 1947–July 6, 1947 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hollister, California |

| Also known as | 1947 Hollister Gypsy Tour[2][3] |

| Participants | 2,000 to 4,000 attendees, including about 750 motorcyclists. Members of the American Motorcyclist Association, Boozefighters, Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington and other motorcycle clubs[3] |

The Hollister riot, also known as the Hollister Invasion,[4] was an event that occurred at the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA)-sanctioned Gypsy Tour motorcycle rally in Hollister, California, from July 3 to 6, 1947.

More motorcyclists than expected flooded the small town to watch the annual rallies, as well as socialize and drink. A few of the motorcyclists caused a commotion in the town.

The incident, known afterwards as the Hollister riot, was sensationalized by the press with reports of bikers "taking over the town" and "pandemonium" in Hollister.[5] The strongest dramatization of the event was a photo of a drunken man sitting on a motorcycle, possibly staged by the photographer by surrounding the scene with discarded beer bottles. It was published in Life magazine and it brought national attention and negative opinion to the event. The Hollister riot helped to give rise to the outlaw biker image.

Rise of motorcycles after World War II

[edit]After World War II, countless veterans came back to America and had a difficult time readjusting to civilian life. They searched for the adventure and adrenaline rush associated with life at war. Civilian life felt too monotonous for some men who also craved feelings of excitement and danger.[3] Others sought the close bonds and camaraderie found between men in the army.[6] Thus, motorcycling emerged as a substitute for wartime experiences such as adventure, excitement, danger and camaraderie.[3] Men who had been a part of the motorcycling world before the war were now joined by thousands of new members. The popularity of motorcycling grew dramatically after World War II because of the effects of the war on veterans.

Event

[edit]Throughout the 1930s, Hollister, California hosted an annual Fourth of July gypsy tour event. Gypsy tours were American Motorcyclist Association-sanctioned racing events that took place all over America and were considered to be the best place for motorcyclists to converge.[7] The annual event consisted of motorcycle races, social activities, and partying.[8] In Hollister, the event and the motorcyclists were welcome, especially because Hollister was a very small town with only about 4,500 people;[9] the rally became a major event in its yearly life[10] as well as an important part of the town's economy. Due to World War II, the rally was canceled, but the event organized for 1947 was the revival of the Gypsy Tour in Hollister.[9]

On July 3, 1947, festivities in Hollister began. However, the popularity of motorcycles had grown dramatically and this rise in popularity caused massive attendance, a major issue. Around 4,000 motorcyclists[5] flooded Hollister, almost doubling the population of the small town. They came from all over California and the United States, even from as far away as Connecticut and Florida.[5] Motorcycle groups in attendance included the 13 Rebels, Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington, the Boozefighters, the Market Street Commandos, the Top Hatters Motorcycle Club, and the Galloping Goose Motorcycle Club.[3][11] Approximately ten percent of attendees were women.[5] The town was completely unprepared for the number of people that arrived, since not as many people had participated in the pre-war years.

Initially, the motorcyclists were welcomed into the Hollister bars as the influx of people meant a boom in business.[12][13] But soon, drunken motorcyclists were riding their bikes through the small streets of Hollister and consuming large amounts of alcohol.[14] They were fighting,[15][unreliable source?] damaging bars, throwing beer bottles out of windows, racing in the streets, and other drunken actions.[5] There was also a severe housing problem. The bikers had to sleep on sidewalks, in parks,[15][unreliable source?] in haystacks and on people's lawns.[5] By the evening of July 4, "they were virtually out of control".[5]

The small, seven-man police force of Hollister was overwhelmed by the events.[5] The police tried to stop the motorcyclists' activities by threatening to use tear gas[10][clarification needed] and arresting as many drunken men as possible. The bars tried to stop the men from drinking by refusing to sell beer and voluntarily closing two hours ahead of time.[5]

Eyewitnesses were quoted as saying, "It's just one hell of a mess",[5] but that "[the motorcyclists] weren't doing anything bad, just riding up and down whooping and hollering; not really doing any harm at all."[16]

The ruckus continued through July 5 and slowly died out at the end of the weekend as the rallies ended and the motorcyclists left town.

At the end of the Fourth of July weekend and the informal riot, Hollister was littered with thousands of beer bottles and other debris[5] and there was some minor storefront damage.[3] About 50 people were arrested, most with misdemeanors such as public intoxication, reckless driving, and disturbing the peace.[5] There were around 60 reported injuries,[15][unreliable source?] of which three were serious, including a broken leg and skull fracture.[5] Other than having to witness the chaos of the weekend, no Hollister residents suffered any physical harm.[10] A City Council member stated, "Luckily, there appears to be no serious damage. These trick riders did more harm to themselves than the town."[5]

Media coverage

[edit]The riot came to national prominence through media coverage of the event.

Shortly after the Fourth of July weekend, two articles were published in the San Francisco Chronicle. With titles "Havoc in Hollister"[8] and "Hollister's Bad Time",[5] they both described the event as "pandemonium"[5] and "terrorism".[5] The Chronicle article did little to cause panic for citizens in the California area as there was other major news occurring at the same time, including local labor strikes.[3] The initial reporting reached a larger audience a few weeks later, with an article published in the July 21, 1947, issue of Life magazine. The article was published in the photojournalism section of Life, relying heavily on graphic images and explanatory text.[3] This was shown as single-page article, with a nearly full-page photo above a 115-word insert of text with the headline "Cyclist's Holiday: He and Friends Terrorize Town."[3]

The large photo, taken by Barney Peterson of the San Francisco Chronicle, shows a drunken man, sitting atop a large motorcycle, holding a beer bottle in each hand and surrounded by many other empty, broken bottles. The man was later identified as Eddie Davenport, a member of the Tulare Riders motorcycle club.[15][unreliable source?]

The reliability of the striking photo has been debated, with some sources suggesting that the scene was overtly staged.[11][3] While the photograph was taken by Barney Petersen of the San Francisco Chronicle.[1] the Chronicle did not run it, nor any other images, in its initial two articles covering the event. The bearded individual standing in the immediate background of the photograph, Gus Deserpa, has said he is sure that the photograph was staged by Petersen, and gave the following account: "I saw two guys scraping all these bottles together, that had been lying in the street. Then they positioned a motorcycle in the middle of the pile. After a while this drunk guy comes staggering out of the bar, and they got him to sit on the motorcycle, and started to take his picture." Deserpa claims he deliberately tried to sabotage the staging by stepping into the shot, but to no avail.[16]

Barney Peterson's colleague at the Chronicle, photographer Jerry Telfer, said it was implausible that Peterson would have faked the photos. Telfer said, "Barney was not the type to fake a picture. Barney was the kind of fellow who had a very keen sense of ethics, pictorial ethics as well as word ethics."[4]

Consequences

[edit]The news of rogue motorcyclists causing havoc in small towns such as Hollister was not comforting to Americans still recovering from World War II and scared of the impending Cold War. The nation started to fear motorcycle "hoodlums" and potential rampages.[15][unreliable source?]

The Hollister riot had little effect on the town. The nationwide fear of motorcyclists did not result in many changes in Hollister. Bikers were welcomed back[clarification needed][10] and rallies continued to be held in the years after the riot. In fact, the town held a 1997 50th anniversary rally to commemorate the event.[3]

The one percenter iconography employed by outlaw motorcycle clubs stems from an apocryphal comment ostensibly made in 1960 by William Berry, a former president of the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA), that 99% of motorcyclists were law-abiding citizens, implying the last one percent were outlaws.[17][18] The alleged AMA comment, supposedly in reference to the Hollister riot of 1947,[19][20][18] is denied by the AMA, who claim to have no record of such a statement to the press and that the story is a misquote.[17][a]

Adaptations

[edit]A short story, "Cyclists' Raid" by Frank Rooney, is based on the events of the Hollister riot and was originally published in the January 1951 issue of Harper's Magazine.[21]

The Hollister riot inspired the 1953 film The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando.[22] While the film bears little resemblance to the actual events,[23] it brought the incident into public light and introduced the popular image of motorcyclists as misfits and outlaws.[10]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In March 1972 (p.3), Chas Deane, the editor of Motorcycle Mechanics, wrote: Motorcycling is a way of life, almost a religion to some and the next best thing to breathing for others. There is no such thing as a "typical motorcyclist"; on the one hand we're outcasts and "one percenters", while on the other hand we are the "in" people.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Petersen, Barney (July 7, 1947), "A July 7, 1947, picture of Eddie Davenport in Hollister", San Francisco Chronicle, retrieved May 24, 2012

- ^ Kresnak, Bill (2008), Motorcycling for Dummies, For Dummies, ISBN 9780470245873

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k William L. Dulaney, "A Brief History of 'Outlaw' Motorcycle Clubs", International Journal of Motorcycle Studies. November 2005. (accessed May 23, 2012)

- ^ a b Smith, Jerry (July 2, 2010), "The Hollister Invasion: The Shot Seen 'Round The World", Cycle Guide, retrieved August 5, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q C. J. Doughty, Jr. "More On Hollister's Bad Time", San Francisco Chronicle July 6, 1947.

- ^ Mark S. Ciacchi. "Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs and the American Vets." Vet Extra 12 (2003): 10-11. Via Dulaney, 2005.

- ^ "The History of the AMA." American Motorcyclist Association (AMA). May 21, 2005. Via Dulaney, 2005.

- ^ a b C. J. Doughty, Jr. "Havoc In Hollister", San Francisco Chronicle July 5, 1947.

- ^ a b Mike Carroll, 1947 Hollister Invasion. (accessed May 23, 2012)

- ^ a b c d e "The Real 'Wild Ones', the 1947 Hollister Motorcycle Riot." Classic Bike 1998.

- ^ a b Stephen L. Mallory, Understanding Organized Crime. (Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett, 2007) 152.

- ^ "History of the Rally." Hollister Independence Rally Committee. 2005. Via Dulaney, 2005.

- ^ Interview with Catherine Dabo. Classic Bike 1998.

- ^ Hollister Independence Rally Committee. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Iconic Photos, The Wild One Riots. (accessed May 23, 2012)

- ^ a b Interview with Gus Deserpa. Classic Bike.

- ^ a b Dulaney, William L. (November 2005), "A Brief History of "Outlaw" Motorcycle Clubs", International Journal of Motorcycle Studies,

The Life story caused something of a tumult around the country (Yates), and some authors have asserted that the AMA subsequently released a press statement disclaiming involvement in the Hollister event, stating that 99% of motorcyclists are good, decent, law-abiding citizens, and that the AMA's ranks of motorcycle clubs were not involved in the debacle (e.g., Reynolds, Thompson). The American Motorcyclist Association says it has no record of ever releasing such as statement. Tom Lindsay, the AMA's Public Information Director, said 'We [the American Motorcyclist Association] acknowledge that the term 'one-percenter' has long been (and likely will continue to be) attributed to the American Motorcyclist Association, but we've been unable to attribute its original use to an AMA official or published statement—so it's apocryphal.'

- ^ a b Bikers brought years of feuding – and guns – to town Michael Beebe and Dan Herbeck, The Buffalo News (October 2, 1994) Archived April 20, 2021, at archive.today

- ^ Dougherty, C.I. (5 July 1947), "Motorcyclists Take Over Town, Many Injured", Transcribed article of the San Francisco Chronicle, archived from the original on 3 November 2015

- ^ Dougherty, C.I. (6 July 1947), "2000 'Gypsycycles' Chug Out of Town and the Natives Sigh 'Never Again'", Transcribed article of the San Francisco Chronicle, archived from the original on 3 November 2015

- ^ Frank Rooney. "Cyclists' Raid: a Story", Harper's Magazine. January 1951. 34–44.

- ^ "How the outlaw biker gang culture got its start in a small California town". Los Angeles Times. May 19, 2015.

- ^ Internet Movie Database, The Wild One, (accessed May 23, 2012)