Serotonin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 5-HT, 5-Hydroxytryptamine, Enteramine, Thrombocytin, 3-(β-Aminoethyl)-5-hydroxyl solution , Thrombotonin |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | raphe nuclei, enterochromaffin cells |

| Target tissues | system-wide |

| Receptors | 5-HT1, 5-HT2, 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 |

| Agonists | Indirectly: SSRIs, MAOIs |

| Precursor | 5-HTP |

| Biosynthesis | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase |

| Metabolism | MAO |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.054 |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

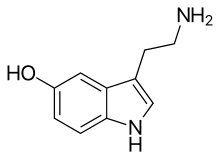

| IUPAC name

5-Hydroxytryptamine

| |

| Preferred IUPAC name

3-(2-Aminoethyl)-1H-indol-5-ol | |

| Other names

5-Hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT, Enteramine; Thrombocytin, 3-(β-Aminoethyl)-5-hydroxyindole, 3-(2-Aminoethyl)indol-5-ol, Thrombotonin

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.054 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Serotonin |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H12N2O | |

| Molar mass | 176.215 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Melting point | 167.7 °C (333.9 °F; 440.8 K) 121–122 °C (ligroin)[3] |

| Boiling point | 416 ± 30 °C (at 760 Torr)[1] |

| slightly soluble | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.16 in water at 23.5 °C[2] |

| 2.98 D | |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

750 mg/kg (subcutaneous, rat),[4] 4500 mg/kg (intraperitoneal, rat),[5] 60 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Serotonin (/ˌsɛrəˈtoʊnɪn, ˌsɪərə-/)[6][7][8] or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex, touching on diverse functions including mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vasoconstriction.[9]

Serotonin is produced in the central nervous system (CNS), specifically in the brainstem's raphe nuclei, the skin's Merkel cells, pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and the tongue's taste receptor cells. Approximately 90% of the serotonin the human body produces is in the gastrointestinal tract's enterochromaffin cells, where it regulates intestinal movements.[10][11][12] Additionally, it is stored in blood platelets and is released during agitation and vasoconstriction, where it then acts as an agonist to other platelets.[13] About 8% is found in platelets and 1–2% in the CNS.[14]

The serotonin is secreted luminally and basolaterally, which leads to increased serotonin uptake by circulating platelets and activation after stimulation, which gives increased stimulation of myenteric neurons and gastrointestinal motility.[15] The remainder is synthesized in serotonergic neurons of the CNS, where it has various functions, including the regulation of mood, appetite, and sleep.[16][unreliable medical source][17][unreliable medical source]

Serotonin secreted from the enterochromaffin cells eventually finds its way out of tissues into the blood. There, it is actively taken up by blood platelets, which store it. When the platelets bind to a clot, they release serotonin, where it can serve as a vasoconstrictor or a vasodilator while regulating hemostasis and blood clotting. In high concentrations, serotonin acts as a vasoconstrictor by contracting endothelial smooth muscle directly or by potentiating the effects of other vasoconstrictors (e.g. angiotensin II and norepinephrine). The vasoconstrictive property is mostly seen in pathologic states affecting the endothelium – such as atherosclerosis or chronic hypertension. In normal physiologic states, vasodilation occurs through the serotonin mediated release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells, and the inhibition of release of norepinephrine from adrenergic nerves.[18] Serotonin is also a growth factor for some types of cells, which may give it a role in wound healing. There are various serotonin receptors.

Biochemically, the indoleamine molecule derives from the amino acid tryptophan. Serotonin is metabolized mainly to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), chiefly by the liver.

Several classes of antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), interfere with the normal reabsorption of serotonin after it is done with the transmission of the signal, therefore augmenting the neurotransmitter levels in the synapses.

Besides mammals, serotonin is found in all bilateral animals including worms and insects,[19] as well as in fungi and in plants.[20] Serotonin's presence in insect venoms and plant spines serves to cause pain, which is a side-effect of serotonin injection.[21][22] Serotonin is produced by pathogenic amoebae, causing diarrhea in the human gut.[23] Its widespread presence in many seeds and fruits may serve to stimulate the digestive tract into expelling the seeds.[24][failed verification]

Molecular structure

[edit]Biochemically, the indoleamine molecule derives from the amino acid tryptophan, via the (rate-limiting) hydroxylation of the 5 position on the ring (forming the intermediate 5-hydroxytryptophan), and then decarboxylation to produce serotonin.[25] Preferable conformations are defined via ethylamine chain, resulting in six different conformations.[26]

Crystal structure

[edit]Serotonin crystallizes in P212121 chiral space group forming different hydrogen-bonding interactions between serotonin molecules via N-H...O and O-H...N intermolecular bonds.[27] Serotonin also forms several salts, including pharmaceutical formulation of serotonin adipate.[28]

Biological role

[edit]Serotonin is involved in numerous physiological processes,[29] including sleep,[30] thermoregulation, learning and memory, pain, (social) behavior,[31] sexual activity, feeding, motor activity, neural development,[32] and biological rhythms.[33] In less complex animals, such as some invertebrates, serotonin regulates feeding and other processes.[34] In plants serotonin synthesis seems to be associated with stress signals.[20][35] Despite its longstanding prominence in pharmaceutical advertising, the claim that low serotonin levels cause depression is not supported by scientific evidence.[36][37][38]

Cellular effects

[edit]Serotonin primarily acts through its receptors and its effects depend on which cells and tissues express these receptors.[33]

Metabolism involves first oxidation by monoamine oxidase to 5-hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde (5-HIAL).[39][40] The rate-limiting step is hydride transfer from serotonin to the flavin cofactor.[41] There follows oxidation by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the indole acetic-acid derivative. The latter is then excreted by the kidneys.

Receptors

[edit]The 5-HT receptors, the receptors for serotonin, are located on the cell membrane of nerve cells and other cell types in animals, and mediate the effects of serotonin as the endogenous ligand and of a broad range of pharmaceutical and psychedelic drugs. Except for the 5-HT3 receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel, all other 5-HT receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors (also called seven-transmembrane, or heptahelical receptors) that activate an intracellular second messenger cascade.[42]

Termination

[edit]Serotonergic action is terminated primarily via uptake of 5-HT from the synapse. This is accomplished through the specific monoamine transporter for 5-HT, SERT, on the presynaptic neuron. Various agents can inhibit 5-HT reuptake, including cocaine, dextromethorphan (an antitussive), tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). A 2006 study found that a significant portion of 5-HT's synaptic clearance is due to the selective activity of the plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT) which actively transports the molecule across the membrane and back into the presynaptic cell.[43]

In contrast to the high affinity of SERT, the PMAT has been identified as a low-affinity transporter, with an apparent Km of 114 micromoles/l for serotonin, which is approximately 230 times higher than that of SERT. However, the PMAT, despite its relatively low serotonergic affinity, has a considerably higher transport "capacity" than SERT, "resulting in roughly comparable uptake efficiencies to SERT ... in heterologous expression systems."[43] The study also suggests that the administration of SSRIs such as fluoxetine and sertraline may be associated with an inhibitory effect on PMAT activity when used at higher than normal dosages (IC50 test values used in trials were 3–4 fold higher than typical prescriptive dosage).

Serotonylation

[edit]Serotonin can also signal through a nonreceptor mechanism called serotonylation, in which serotonin modifies proteins.[44] This process underlies serotonin's effects upon platelet-forming cells (thrombocytes) in which it links to the modification of signaling enzymes called GTPases that then trigger the release of vesicle contents by exocytosis.[45] A similar process underlies the pancreatic release of insulin.[44]

The effects of serotonin upon vascular smooth muscle tone – the biological function after which serotonin was originally named – depend upon the serotonylation of proteins involved in the contractile apparatus of muscle cells.[46]

| Receptor | Ki (nM)[47] | Receptor function[Note 1] |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1 receptor family signals via Gi/o inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. | ||

| 5-HT1A | 3.17 | Memory[vague] (agonists ↓); learning[vague] (agonists ↓); anxiety (agonists ↓); depression (agonists ↓); positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia (partial agonists ↓); analgesia (agonists ↑); aggression (agonists ↓); dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex (agonists ↑); serotonin release and synthesis (agonists ↓) |

| 5-HT1B | 4.32 | Vasoconstriction (agonists ↑); aggression (agonists ↓); bone mass (↓). Serotonin autoreceptor. |

| 5-HT1D | 5.03 | Vasoconstriction (agonists ↑) |

| 5-HT1E | 7.53 | |

| 5-HT1F | 10 | |

| 5-HT2 receptor family signals via Gq activation of phospholipase C. | ||

| 5-HT2A | 11.55 | Psychedelia (agonists ↑); depression (agonists & antagonists ↓); anxiety (antagonists ↓); positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (antagonists ↓); norepinephrine release from the locus coeruleus (antagonists ↑); glutamate release in the prefrontal cortex (agonists ↑); dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (agonists ↑);[48] urinary bladder contractions (agonists ↑)[49] |

| 5-HT2B | 8.71 | Cardiovascular functioning (agonists increase risk of pulmonary hypertension), empathy (via von Economo neurons[50]) |

| 5-HT2C | 5.02 | Dopamine release into the mesocorticolimbic pathway (agonists ↓); acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex (agonists ↑); dopaminergic and noradrenergic activity in the frontal cortex (antagonists ↑);[51] appetite (agonists ↓); antipsychotic effects (agonists ↑); antidepressant effects (agonists & antagonists ↑) |

| Other 5-HT receptors | ||

| 5-HT3 | 593 | Emesis (agonists ↑); anxiolysis (antagonists ↑). |

| 5-HT4 | 125.89 | Movement of food across the GI tract (agonists ↑); memory & learning (agonists ↑); antidepressant effects (agonists ↑). Signalling via Gαs activation of adenylyl cyclase. |

| 5-HT5A | 251.2 | Memory consolidation.[52] Signals via Gi/o inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. |

| 5-HT6 | 98.41 | Cognition (antagonists ↑); antidepressant effects (agonists & antagonists ↑); anxiogenic effects (antagonists ↑[53]). Gs signalling via activating adenylyl cyclase. |

| 5-HT7 | 8.11 | Cognition (antagonists ↑); antidepressant effects (antagonists ↑). Acts by Gs signalling via activating adenylyl cyclase. |

Nervous system

[edit]

The neurons of the raphe nuclei are the principal source of 5-HT release in the brain.[54] There are nine raphe nuclei, designated B1–B9, which contain the majority of serotonin-containing neurons (some scientists chose to group the nuclei raphes lineares into one nucleus), all of which are located along the midline of the brainstem, and centered on the reticular formation.[55][56] Axons from the neurons of the raphe nuclei form a neurotransmitter system reaching almost every part of the central nervous system. Axons of neurons in the lower raphe nuclei terminate in the cerebellum and spinal cord, while the axons of the higher nuclei spread out in the entire brain.

Ultrastructure and function

[edit]The serotonin nuclei may also be divided into two main groups, the rostral and caudal containing three and four nuclei respectively. The rostral group consists of the caudal linear nuclei (B8), the dorsal raphe nuclei (B6 and B7) and the median raphe nuclei (B5, B8 and B9), that project into multiple cortical and subcortical structures. The caudal group consists of the nucleus raphe magnus (B3), raphe obscurus nucleus (B2), raphe pallidus nucleus (B1), and lateral medullary reticular formation, that project into the brainstem.[57]

The serotonergic pathway is involved in sensorimotor function, with pathways projecting both into cortical (Dorsal and Median Raphe Nuclei), subcortical, and spinal areas involved in motor activity. Pharmacological manipulation suggests that serotonergic activity increases with motor activity while firing rates of serotonergic neurons increase with intense visual stimuli. Animal models suggest that kainate signaling negatively regulates serotonin actions in the retina, with possible implications for the control of the visual system.[58] The descending projections form a pathway that inhibits pain called the "descending inhibitory pathway" that may be relevant to a disorder such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and other pain disorders, and the efficacy of antidepressants in them.[59]

Serotonergic projections from the caudal nuclei are involved in regulating mood and emotion, and hypo-[60] or hyper-serotonergic[61] states may be involved in depression and sickness behavior.

Microanatomy

[edit]Serotonin is released into the synapse, or space between neurons, and diffuses over a relatively wide gap (>20 nm) to activate 5-HT receptors located on the dendrites, cell bodies, and presynaptic terminals of adjacent neurons.

When humans smell food, dopamine is released to increase the appetite. But, unlike in worms, serotonin does not increase anticipatory behaviour in humans; instead, the serotonin released while consuming activates 5-HT2C receptors on dopamine-producing cells. This halts their dopamine release, and thereby serotonin decreases appetite. Drugs that block 5-HT2C receptors make the body unable to recognize when it is no longer hungry or otherwise in need of nutrients, and are associated with weight gain,[62] especially in people with a low number of receptors.[63] The expression of 5-HT2C receptors in the hippocampus follows a diurnal rhythm,[64] just as the serotonin release in the ventromedial nucleus, which is characterised by a peak at morning when the motivation to eat is strongest.[65]

In macaques, alpha males have twice the level of serotonin in the brain as subordinate males and females (measured by the concentration of 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)). Dominance status and CSF serotonin levels appear to be positively correlated. When dominant males were removed from such groups, subordinate males begin competing for dominance. Once new dominance hierarchies were established, serotonin levels of the new dominant individuals also increased to double those in subordinate males and females. The reason why serotonin levels are only high in dominant males, but not dominant females has not yet been established.[66]

In humans, levels of 5-HT1A receptor inhibition in the brain show negative correlation with aggression,[67] and a mutation in the gene that codes for the 5-HT2A receptor may double the risk of suicide for those with that genotype.[68] Serotonin in the brain is not usually degraded after use, but is collected by serotonergic neurons by serotonin transporters on their cell surfaces. Studies have revealed nearly 10% of total variance in anxiety-related personality depends on variations in the description of where, when and how many serotonin transporters the neurons should deploy.[69]

Outside the nervous system

[edit]Digestive tract (emetic)

[edit]Serotonin regulates gastrointestinal (GI) function. The gut is surrounded by enterochromaffin cells, which release serotonin in response to food in the lumen. This makes the gut contract around the food. Platelets in the veins draining the gut collect excess serotonin. There are often serotonin abnormalities in gastrointestinal disorders such as constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.[70]

If irritants are present in the food, the enterochromaffin cells release more serotonin to make the gut move faster, i.e., to cause diarrhea, so the gut is emptied of the noxious substance. If serotonin is released in the blood faster than the platelets can absorb it, the level of free serotonin in the blood is increased. This activates 5-HT3 receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone that stimulate vomiting.[71] Thus, drugs and toxins stimulate serotonin release from enterochromaffin cells in the gut wall can induce emesis. The enterochromaffin cells not only react to bad food but are also very sensitive to irradiation and cancer chemotherapy. Drugs that block 5HT3 are very effective in controlling the nausea and vomiting produced by cancer treatment, and are considered the gold standard for this purpose.[72]

Lungs

[edit]The lung,[73] including that of reptiles,[74] contains specialized epithelial cells that occur as solitary cells or as clusters called neuroepithelial bodies or bronchial Kulchitsky cells or alternatively K cells.[75] These are enterochromaffin cells that like those in the gut release serotonin.[75] Their function is probably vasoconstriction during hypoxia.[73]

Skin

[edit]Serotonin is also produced by Merkel cells which are part of the somatosensory system.[76]

Bone metabolism

[edit]In mice and humans, alterations in serotonin levels and signalling have been shown to regulate bone mass.[77][78][79][80] Mice that lack brain serotonin have osteopenia, while mice that lack gut serotonin have high bone density. In humans, increased blood serotonin levels have been shown to be a significant negative predictor of low bone density. Serotonin can also be synthesized, albeit at very low levels, in the bone cells. It mediates its actions on bone cells using three different receptors. Through 5-HT1B receptors, it negatively regulates bone mass, while it does so positively through 5-HT2B receptors and 5-HT2C receptors. There is very delicate balance between physiological role of gut serotonin and its pathology. Increase in the extracellular content of serotonin results in a complex relay of signals in the osteoblasts culminating in FoxO1/ Creb and ATF4 dependent transcriptional events.[81] Following the 2008 findings that gut serotonin regulates bone mass, the mechanistic investigations into what regulates serotonin synthesis from the gut in the regulation of bone mass have started. Piezo1 has been shown to sense RNA in the gut and relay this information through serotonin synthesis to the bone by acting as a sensor of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) governing 5-HT production. Intestinal epithelium-specific deletion of mouse Piezo1 profoundly disturbed gut peristalsis, impeded experimental colitis, and suppressed serum 5-HT levels. Because of systemic 5-HT deficiency, conditional knockout of Piezo1 increased bone formation. Notably, fecal ssRNA was identified as a natural Piezo1 ligand, and ssRNA-stimulated 5-HT synthesis from the gut was evoked in a MyD88/TRIF-independent manner. Colonic infusion of RNase A suppressed gut motility and increased bone mass. These findings suggest gut ssRNA as a master determinant of systemic 5-HT levels, indicating the ssRNA-Piezo1 axis as a potential prophylactic target for treatment of bone and gut disorders. Studies in 2008, 2010 and 2019 have opened the potential for serotonin research to treat bone mass disorders.[82][83]

Organ development

[edit]Since serotonin signals resource availability it is not surprising that it affects organ development. Many human and animal studies have shown that nutrition in early life can influence, in adulthood, such things as body fatness, blood lipids, blood pressure, atherosclerosis, behavior, learning, and longevity.[84][85][86] Rodent experiment shows that neonatal exposure to SSRIs makes persistent changes in the serotonergic transmission of the brain resulting in behavioral changes,[87][88] which are reversed by treatment with antidepressants.[89] By treating normal and knockout mice lacking the serotonin transporter with fluoxetine scientists showed that normal emotional reactions in adulthood, like a short latency to escape foot shocks and inclination to explore new environments were dependent on active serotonin transporters during the neonatal period.[90][91]

Human serotonin can also act as a growth factor directly. Liver damage increases cellular expression of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors, mediating liver compensatory regrowth (see Liver § Regeneration and transplantation)[92] Serotonin present in the blood then stimulates cellular growth to repair liver damage.[93]

5-HT2B receptors also activate osteocytes, which build up bone[94] However, serotonin also inhibits osteoblasts, through 5-HT1B receptors.[95]

Cardiovascular growth factor

[edit]Serotonin, in addition, evokes endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation and stimulates, through a 5-HT1B receptor-mediated mechanism, the phosphorylation of p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in bovine aortic endothelial cell cultures.[clarification needed][96] In blood, serotonin is collected from plasma by platelets, which store it. It is thus active wherever platelets bind in damaged tissue, as a vasoconstrictor to stop bleeding, and also as a fibrocyte mitotic (growth factor), to aid healing.[97]

Pharmacology

[edit]Several classes of drugs target the serotonin system, including some antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, analgesics, antimigraine drugs, antiemetics, appetite suppressants, and anticonvulsants, as well as psychedelics and entactogens.

Mechanism of action

[edit]At rest, serotonin is stored within the vesicles of presynaptic neurons. When stimulated by nerve impulses, serotonin is released as a neurotransmitter into the synapse, reversibly binding to the postsynaptic receptor to induce a nerve impulse on the postsynaptic neuron. Serotonin can also bind to auto-receptors on the presynaptic neuron to regulate the synthesis and release of serotonin. Normally serotonin is taken back into the presynaptic neuron to stop its action, then reused or broken down by monoamine oxidase.[98]

Antidepressants

[edit]Drugs that alter serotonin levels are used in treating depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) prevent the breakdown of monoamine neurotransmitters (including serotonin), and therefore increase concentrations of the neurotransmitter in the brain. MAOI therapy is associated with many adverse drug reactions, and patients are at risk of hypertensive emergency triggered by foods with high tyramine content, and certain drugs. Some drugs inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin, making it stay in the synaptic cleft longer. The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. The newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have fewer side-effects and fewer interactions with other drugs.[99]

Certain SSRI medications have been shown to lower serotonin levels below the baseline after chronic use, despite initial increases.[100] The 5-HTTLPR gene codes for the number of serotonin transporters in the brain, with more serotonin transporters causing decreased duration and magnitude of serotonergic signaling.[101] The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism (l/l) causing more serotonin transporters to be formed is also found to be more resilient against depression and anxiety.[102][103]

Besides their use in treating depression and anxiety, certain serotonergic antidepressants are also approved and used to treat fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain, and chronic fatigue syndrome.[104][105]

Anxiolytics

[edit]Azapirone anxiolytics like buspirone and tandospirone act as serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonists.[106][107]

Antipsychotics

[edit]Many antipsychotics bind to and modulate serotonin receptors, including the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, among others.[108][109] Activation of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and blockade of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors may contribute to the therapeutic antipsychotic effects of these agents, whereas antagonism of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors has been especially implicated in side effects of antipsychotics.[108][109]

Antimigraine agents

[edit]Antimigraine agents such as the triptans like sumatriptan act as agonists of the serotonin 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and/or 5-HT1F receptors.[110][111] Earlier antimigraine agents were the ergoline derivatives and ergot-related drugs such as ergotamine, dihydroergotamine, and methysergide, which act as non-selective serotonin receptor agonists.[111][112][113]

Antiemetics

[edit]Some serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, such as ondansetron, granisetron, and tropisetron, are important antiemetic agents.[114][115] They are particularly important in treating the nausea and vomiting that occur during anticancer chemotherapy using cytotoxic drugs.[115] Another application is in the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting.[114]

Appetite suppressants

[edit]Some serotonin releasing agents, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and/or serotonin 5-HT2C receptor agonists, such as fenfluramine, dexfenfluramine, chlorphentermine, sibutramine, and lorcaserin, have been approved and used as appetite suppressants for purposes of weight loss in the treatment of overweightness or obesity.[116][117][118][119][120] Several of the preceding agents have been withdrawn from the market due to toxicity, such as cardiac fibrosis or pulmonary hypertension.[120]

Anticonvulsants

[edit]Although it was previously withdrawn from the market as an appetite suppressant, fenfluramine was reintroduced as an anticonvulsant for treatment of seizures in certain rare forms of epilepsy like Dravet syndrome and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.[121] Selective serotonin 5-HT2C receptor agonists, like lorcaserin, bexicaserin, and BMB-101, are also being developed for this use.[121][122][123][124]

Psychedelics

[edit]Serotonergic psychedelics, including drugs like psilocybin (found in psilocybin mushrooms), dimethyltryptamine (DMT) (found in ayahuasca), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), mescaline (found in peyote cactus), and 5-MeO-DMT (found in Anadenanthera trees and the Bufo alvarius toad), are non-selective agonists of the serotonin receptors and mediate their hallucinogenic effects specifically by activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[125][126][127] This is evidenced by the fact that serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists and so-called "trip killers" like ketanserin block the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics in humans, among many other findings.[125][126][128] Some serotonergic psychedelics, like psilocin, DMT, and 5-MeO-DMT, are substituted tryptamines and are very similar in chemical structure to serotonin.[127]

Serotonin itself, despite acting as a serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist, is thought to be non-hallucinogenic.[129] The hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics appear to be mediated specifically by activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors expressed in a population of cortical neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[130][129] These serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, unlike most serotonin and related receptors, are expressed intracellularly.[130][129] In addition, the neurons containing them lack expression of the serotonin transporter (SERT), which normally transports serotonin from the extracellular space to the intracellular space within neurons.[130][129] Serotonin itself is too hydrophilic to enter serotonergic neurons without the SERT, and hence these serotonin 5-HT2A receptors are inaccessible to serotonin.[130][129] Conversely, serotonergic psychedelics are more lipophilic than serotonin and readily enter these neurons.[130][129] In addition to explaining why serotonin does not show psychedelic effects, these findings may explain why drugs that increase serotonin levels, like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and various other types of serotonergic agents, do not produce psychedelic effects.[130][129] Artificial expression of the SERT in these medial prefrontal cortex neurons resulted in the serotonin releasing agent para-chloroamphetamine (PCA), which does not normally show psychedelic-like effects, being able to produce psychedelic-like effects in animals.[129]

Although serotonin itself is non-hallucinogenic, administration of very high doses of a serotonin precursor, like tryptophan or 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), or intracerebroventricular injection of high doses of serotonin directly into the brain, can produce psychedelic-like effects in animals.[131][132][133] These psychedelic-like effects can be abolished by indolethylamine N-methyltransferase (INMT) inhibitors, which block conversion of serotonin and other endogenous tryptamines into N-methylated tryptamines, including N-methylserotonin (NMS; norbufotenin), bufotenin (5-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine; 5-HO-DMT), N-methyltryptamine (NMT), and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT).[132][134][133] These N-methyltryptamines are much more lipophilic than serotonin and, in contrast, are able to diffuse into serotonergic neurons and activate intracellular serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[132][133][130][129]

DMT is a naturally occurring endogenous compound in the body.[135][136][137] In relation to the fact that serotonin itself is unable to activate intracellular serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, it is possible that DMT might be the endogenous ligand of these receptors rather than serotonin.[130][129]

Entactogens

[edit]The entactogen MDMA is a serotonin releasing agent and, while it also possesses other actions such as concomitant release of norepinephrine and dopamine and weak direct agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, its serotonin release plays a key role in its unique entactogenic effects.[138] Entactogens like MDMA should be distinguished from other drugs such as stimulants like amphetamine and psychedelics like LSD, although MDMA itself also has some characteristics of both of these types of agents.[138][139] Coadministration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which block the serotonin transporter (SERT) and prevent MDMA from inducing serotonin release, markedly reduce the subjective effects of MDMA, demonstrating the key role of serotonin in the effects of the drug.[140] Serotonin releasing agents like MDMA achieve much greater increases in serotonin levels than SSRIs and have far more robust of subjective effects.[141][142][143][144] Besides MDMA, many other entactogens also exist and are known.[145][146][139]

Serotonin syndrome

[edit]Extremely high levels of serotonin or activation of certain serotonin receptors can cause a condition known as serotonin syndrome, with toxic and potentially fatal effects. In practice, such toxic levels are essentially impossible to reach through an overdose of a single antidepressant drug, but require a combination of serotonergic agents, such as an SSRI with a MAOI, which may occur in therapeutic doses.[147][148] However, serotonin syndrome can occur with overdose of certain serotonin receptor agonists, like the NBOMe series of serotonergic psychedelics.[149][150][151]

The intensity of the symptoms of serotonin syndrome vary over a wide spectrum, and the milder forms are seen even at nontoxic levels.[152] It is estimated that 14% of patients experiencing serotonin syndrome overdose on SSRIs; meanwhile the fatality rate is between 2% and 12%.[147][153][154]

Cardiac fibrosis and other fibroses

[edit]Some serotonergic agonist drugs cause fibrosis anywhere in the body, particularly the syndrome of retroperitoneal fibrosis, as well as cardiac valve fibrosis.[155]

In the past, three groups of serotonergic drugs have been epidemiologically linked with these syndromes. These are the serotonergic vasoconstrictive antimigraine drugs (ergotamine and methysergide),[155] the serotonergic appetite suppressant drugs (fenfluramine, chlorphentermine, and aminorex), and certain anti-Parkinsonian dopaminergic agonists, which also stimulate serotonergic 5-HT2B receptors. These include pergolide and cabergoline, but not the more dopamine-specific lisuride.[156]

As with fenfluramine, some of these drugs have been withdrawn from the market after groups taking them showed a statistical increase of one or more of the side effects described. An example is pergolide. The drug was declining in use since it was reported in 2003 to be associated with cardiac fibrosis.[157]

Two independent studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine in January 2007 implicated pergolide, along with cabergoline, in causing valvular heart disease.[158][159] As a result of this, the FDA removed pergolide from the United States market in March 2007.[160] (Since cabergoline is not approved in the United States for Parkinson's Disease, but for hyperprolactinemia, the drug remains on the market. Treatment for hyperprolactinemia requires lower doses than that for Parkinson's Disease, diminishing the risk of valvular heart disease).[161]

Comparative biology and evolution

[edit]Unicellular organisms

[edit]Serotonin is used by a variety of single-cell organisms for various purposes. SSRIs have been found to be toxic to algae.[162] The gastrointestinal parasite Entamoeba histolytica secretes serotonin, causing a sustained secretory diarrhea in some people.[23][163] Patients infected with E. histolytica have been found to have highly elevated serum serotonin levels, which returned to normal following resolution of the infection.[164] E. histolytica also responds to the presence of serotonin by becoming more virulent.[165] This means serotonin secretion not only serves to increase the spread of entamoebas by giving the host diarrhea but also serves to coordinate their behaviour according to their population density, a phenomenon known as quorum sensing. Outside the gut of a host, there is nothing that the entamoebas provoke to release serotonin, hence the serotonin concentration is very low. Low serotonin signals to the entamoebas they are outside a host and they become less virulent to conserve energy. When they enter a new host, they multiply in the gut, and become more virulent as the enterochromaffine cells get provoked by them and the serotonin concentration increases.

Edible plants and mushrooms

[edit]In drying seeds, serotonin production is a way to get rid of the buildup of poisonous ammonia. The ammonia is collected and placed in the indole part of L-tryptophan, which is then decarboxylated by tryptophan decarboxylase to give tryptamine, which is then hydroxylated by a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, yielding serotonin.[166]

However, since serotonin is a major gastrointestinal tract modulator, it may be produced in the fruits of plants as a way of speeding the passage of seeds through the digestive tract, in the same way as many well-known seed and fruit associated laxatives. Serotonin is found in mushrooms, fruits, and vegetables. The highest values of 25–400 mg/kg have been found in nuts of the walnut (Juglans) and hickory (Carya) genera. Serotonin concentrations of 3–30 mg/kg have been found in plantains, pineapples, banana, kiwifruit, plums, and tomatoes. Moderate levels from 0.1–3 mg/kg have been found in a wide range of tested vegetables.[24][20]

Serotonin is one compound of the poison contained in stinging nettles (Urtica dioica), where it causes pain on injection in the same manner as its presence in insect venoms.[22] It is also naturally found in Paramuricea clavata, or the Red Sea Fan.[167]

Serotonin and tryptophan have been found in chocolate with varying cocoa contents. The highest serotonin content (2.93 μg/g) was found in chocolate with 85% cocoa, and the highest tryptophan content (13.27–13.34 μg/g) was found in 70–85% cocoa. The intermediate in the synthesis from tryptophan to serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptophan, was not found.[168]

Root development in Arabidopsis thaliana is stimulated and modulated by serotonin – in various ways at various concentrations.[169]

Serotonin serves as a plant defense chemical against fungi. When infected with Fusarium crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum), wheat (Triticum aestivum) greatly increases its production of tryptophan to synthesize new serotonin.[170] The function of this is poorly understood[170] but wheat also produces serotonin when infected by Stagonospora nodorum – in that case to retard spore production.[171] The model cereal Brachypodium distachyon – used as a research substitute for wheat and other production cereals – also produces serotonin, coumaroyl-serotonin, and feruloyl-serotonin in response to F. graminearum. This produces a slight antimicrobial effect. B. distachyon produces more serotonin (and conjugates) in response to deoxynivalenol (DON)-producing F. graminearum than non-DON-producing.[172] Solanum lycopersicum produces many AA conjugates – including several of serotonin – in its leaves, stems, and roots in response to Ralstonia solanacearum infection.[173]

Serotonin occurs in several hallucinogenic mushrooms of the genus Panaeolus.[174]

Invertebrates

[edit]Serotonin functions as a neurotransmitter in the nervous systems of most animals.

Nematodes

[edit]For example, in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, which feeds on bacteria, serotonin is released as a signal in response to positive events, such as finding a new source of food or in male animals finding a female with which to mate.[175] When a well-fed worm feels bacteria on its cuticle, dopamine is released, which slows it down; if it is starved, serotonin also is released, which slows the animal down further. This mechanism increases the amount of time animals spend in the presence of food.[176] The released serotonin activates the muscles used for feeding, while octopamine suppresses them.[177][178] Serotonin diffuses to serotonin-sensitive neurons, which control the animal's perception of nutrient availability.

Decapods

[edit]If lobsters are injected with serotonin, they behave like dominant individuals whereas octopamine causes subordinate behavior.[31] A crayfish that is frightened may flip its tail to flee, and the effect of serotonin on this behavior depends largely on the animal's social status. Serotonin inhibits the fleeing reaction in subordinates, but enhances it in socially dominant or isolated individuals. The reason for this is social experience alters the proportion between serotonin receptors (5-HT receptors) that have opposing effects on the fight-or-flight response.[clarification needed] The effect of 5-HT1 receptors predominates in subordinate animals, while 5-HT2 receptors predominates in dominants.[179]

In venoms

[edit]Serotonin is a common component of invertebrate venoms, salivary glands, nervous tissues, and various other tissues, across molluscs, insects, crustaceans, scorpions, various kinds of worms, and jellyfish.[22] Adult Rhodnius prolixus – hematophagous on vertebrates – secrete lipocalins into the wound during feeding. In 2003 these lipocalins were demonstrated to sequester serotonin to prevent vasoconstriction (and possibly coagulation) in the host.[180]

Insects

[edit]Serotonin is evolutionarily conserved and appears across the animal kingdom. It is seen in insect processes in roles similar to in the human central nervous system, such as memory, appetite, sleep, and behavior.[181][19] Some circuits in mushroom bodies are serotonergic.[182] (See specific Drosophila example below, §Dipterans.)

Acrididae

[edit]Locust swarming is initiated but not maintained by serotonin,[183] with release being triggered by tactile contact between individuals.[184] This transforms social preference from aversion to a gregarious state that enables coherent groups.[185][184][183] Learning in flies and honeybees is affected by the presence of serotonin.[186][187]

Role in insecticides

[edit]Insect 5-HT receptors have similar sequences to the vertebrate versions, but pharmacological differences have been seen. Invertebrate drug response has been far less characterized than mammalian pharmacology and the potential for species selective insecticides has been discussed.[188]

Hymenopterans

[edit]Wasps and hornets have serotonin in their venom,[189] which causes pain and inflammation[21][22] as do scorpions.[190][22] Pheidole dentata takes on more and more tasks in the colony as it gets older, which requires it to respond to more and more olfactory cues in the course of performing them. This olfactory response broadening was demonstrated to go along with increased serotonin and dopamine, but not octopamine in 2006.[191]

Dipterans

[edit]If flies are fed serotonin, they are more aggressive; flies depleted of serotonin still exhibit aggression, but they do so much less frequently.[192] In their crops it plays a vital role in digestive motility produced by contraction. Serotonin that acts on the crop is exogenous to the crop itself and 2012 research suggested that it probably originated in the serotonin neural plexus in the thoracic-abdominal synganglion.[193] In 2011 a Drosophila serotonergic mushroom body was found to work in concert with Amnesiac to form memories.[182] In 2007 serotonin was found to promote aggression in Diptera, which was counteracted by neuropeptide F – a surprising find given that they both promote courtship, which is usually similar to aggression in most respects.[182]

Vertebrates

[edit]Serotonin, also referred to as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a neurotransmitter most known for its involvement in mood disorders in humans. It is also a widely present neuromodulator among vertebrates and invertebrates.[194] Serotonin has been found having associations with many physiological systems such as cardiovascular, thermoregulation, and behavioral functions, including: circadian rhythm, appetite, aggressive and sexual behavior, sensorimotor reactivity and learning, and pain sensitivity.[195] Serotonin's function in neurological systems along with specific behaviors among vertebrates found to be strongly associated with serotonin will be further discussed. Two relevant case studies are also mentioned regarding serotonin development involving teleost fish and mice.

In mammals, 5-HT is highly concentrated in the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area and raphe nuclei. Lesser concentrated areas include other brain regions and the spinal cord.[194] 5-HT neurons are also shown to be highly branched, indicating that they are structurally prominent for influencing multiple areas of the CNS at the same time, although this trend is exclusive solely to mammals.[195]

5-HT system in vertebrates

[edit]Vertebrates are multicellular organisms in the phylum Chordata that possess a backbone and a nervous system. This includes mammals, fish, reptiles, birds, etc. In humans, the nervous system is composed of the central and peripheral nervous system, with little known about the specific mechanisms of neurotransmitters in most other vertebrates. However, it is known that while serotonin is involved in stress and behavioral responses, it is also important in cognitive functions.[194] Brain organization in most vertebrates includes 5-HT cells in the hindbrain.[194] In addition to this, 5-HT is often found in other sections of the brain in non-placental vertebrates, including the basal forebrain and pretectum.[196] Since location of serotonin receptors contribute to behavioral responses, this suggests serotonin is part of specific pathways in non-placental vertebrates that are not present in amniotic organisms.[197] Teleost fish and mice are organisms most often used to study the connection between serotonin and vertebrate behavior. Both organisms show similarities in the effect of serotonin on behavior, but differ in the mechanism in which the responses occur.

Dogs / canine species

[edit]There are few studies of serotonin in dogs. One study reported serotonin values were higher at dawn than at dusk.[198] In another study, serum 5-HT levels did not seem to be associated with dogs' behavioural response to a stressful situation.[199] Urinary serotonin/creatinine ratio in bitches tended to be higher 4 weeks after surgery. In addition, serotonin was positively correlated with both cortisol and progesterone but not with testosterone after ovariohysterectomy.[200]

Teleost fish

[edit]Like non-placental vertebrates, teleost fish also possess 5-HT cells in other sections of the brain, including the basal forebrain.[196] Danio rerio (zebra fish) are a species of teleost fish often used for studying serotonin within the brain. Despite much being unknown about serotonergic systems in vertebrates, the importance in moderating stress and social interaction is known.[201] It is hypothesized that AVT and CRF cooperate with serotonin in the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis.[196] These neuropeptides influence the plasticity of the teleost, affecting its ability to change and respond to its environment. Subordinate fish in social settings show a drastic increase in 5-HT concentrations.[201] High levels of 5-HT long term influence the inhibition of aggression in subordinate fish.[201]

Mice

[edit]Researchers at the Department of Pharmacology and Medical Chemistry used serotonergic drugs on male mice to study the effects of selected drugs on their behavior.[202] Mice in isolation exhibit increased levels of agonistic behavior towards one another. Results found that serotonergic drugs reduce aggression in isolated mice while simultaneously increasing social interaction.[202] Each of the treatments use a different mechanism for targeting aggression, but ultimately all have the same outcome. While the study shows that serotonergic drugs successfully target serotonin receptors, it does not show specifics of the mechanisms that affect behavior, as all types of drugs tended to reduce aggression in isolated male mice.[202] Aggressive mice kept out of isolation may respond differently to changes in serotonin reuptake.

Behavior

[edit]Like in humans, serotonin is extremely involved in regulating behavior in most other vertebrates. This includes not only response and social behaviors, but also influencing mood. Defects in serotonin pathways can lead to intense variations in mood, as well as symptoms of mood disorders, which can be present in more than just humans.

Social interaction

[edit]One of the most researched aspects of social interaction in which serotonin is involved is aggression. Aggression is regulated by the 5-HT system, as serotonin levels can both induce or inhibit aggressive behaviors, as seen in mice (see section on Mice) and crabs.[202] While this is widely accepted, it is unknown if serotonin interacts directly or indirectly with parts of the brain influencing aggression and other behaviors.[194] Studies of serotonin levels show that they drastically increase and decrease during social interactions, and they generally correlate with inhibiting or inciting aggressive behavior.[203] The exact mechanism of serotonin influencing social behaviors is unknown, as pathways in the 5-HT system in various vertebrates can differ greatly.[194]

Response to stimuli

[edit]Serotonin is important in environmental response pathways, along with other neurotransmitters.[204] Specifically, it has been found to be involved in auditory processing in social settings, as primary sensory systems are connected to social interactions.[205] Serotonin is found in the IC structure of the midbrain, which processes specie specific and non-specific social interactions and vocalizations.[205] It also receives acoustic projections that convey signals to auditory processing regions.[205] Research has proposed that serotonin shapes the auditory information being received by the IC and therefore is influential in the responses to auditory stimuli.[205] This can influence how an organism responds to the sounds of predatory or other impactful species in their environment, as serotonin uptake can influence aggression or social interaction.

Mood

[edit]We can describe mood not as specific to an emotional status, but as associated with a relatively long-lasting emotional state. Serotonin's association with mood is most known for various forms of depression and bipolar disorders in humans.[195] Disorders caused by serotonergic activity potentially contribute to the many symptoms of major depression, such as overall mood, activity, suicidal thoughts and sexual and cognitive dysfunction. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's) are a class of drugs demonstrated to be an effective treatment in major depressive disorder and are the most prescribed class of antidepressants. SSRI's function is to block the reuptake of serotonin, making more serotonin available to absorb by the receiving neuron. Animals have been studied for decades in order to understand depressive behavior among species. One of the most familiar studies, the forced swimming test (FST), was performed to measure potential antidepressant activity.[195] Rats were placed in an inescapable container of water, at which point time spent immobile and number of active behaviors (such as splashing or climbing) were compared before and after a panel of anti-depressant drugs were administered. Antidepressants that selectively inhibit NE reuptake were shown to reduce immobility and selectively increase climbing without affecting swimming. However, results of the SSRI's also show reduced immobility but increased swimming without affecting climbing. This study demonstrated the importance of behavioral tests for antidepressants, as they can detect drugs with an effect on core behavior along with behavioral components of species.[195]

Growth and reproduction

[edit]In the nematode C. elegans, artificial depletion of serotonin or the increase of octopamine cues behavior typical of a low-food environment: C. elegans becomes more active, and mating and egg-laying are suppressed, while the opposite occurs if serotonin is increased or octopamine is decreased in this animal.[34] Serotonin is necessary for normal nematode male mating behavior,[206] and the inclination to leave food to search for a mate.[207] The serotonergic signaling used to adapt the worm's behaviour to fast changes in the environment affects insulin-like signaling and the TGF beta signaling pathway,[208] which control long-term adaption.

In the fruit fly insulin both regulates blood sugar as well as acting as a growth factor. Thus, in the fruit fly, serotonergic neurons regulate the adult body size by affecting insulin secretion.[209][210] Serotonin has also been identified as the trigger for swarm behavior in locusts.[185] In humans, though insulin regulates blood sugar and IGF regulates growth, serotonin controls the release of both hormones, modulating insulin release from the beta cells in the pancreas through serotonylation of GTPase signaling proteins.[44] Exposure to SSRIs during pregnancy reduces fetal growth.[211]

Genetically altered C. elegans worms that lack serotonin have an increased reproductive lifespan, may become obese, and sometimes present with arrested development at a dormant larval state.[212][213]

Aging and age-related phenotypes

[edit]Serotonin is known to regulate aging, learning, and memory. The first evidence comes from the study of longevity in C. elegans.[208] During early phase of aging[vague], the level of serotonin increases, which alters locomotory behaviors and associative memory.[214] The effect is restored by mutations and drugs (including mianserin and methiothepin) that inhibit serotonin receptors. The observation does not contradict with the notion that the serotonin level goes down in mammals and humans, which is typically seen in late but not early[vague] phase of aging.

Biochemical mechanisms

[edit]Biosynthesis

[edit]

In animals and humans, serotonin is synthesized from the amino acid L-tryptophan by a short metabolic pathway consisting of two enzymes, tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (DDC), and the coenzyme pyridoxal phosphate. The TPH-mediated reaction is the rate-limiting step in the pathway.

TPH has been shown to exist in two forms: TPH1, found in several tissues, and TPH2, which is a neuron-specific isoform.[215]

Serotonin can be synthesized from tryptophan in the lab using Aspergillus niger and Psilocybe coprophila as catalysts. The first phase to 5-hydroxytryptophan would require letting tryptophan sit in ethanol and water for 7 days, then mixing in enough HCl (or other acid) to bring the pH to 3, and then adding NaOH to make a pH of 13 for 1 hour. Aspergillus niger would be the catalyst for this first phase. The second phase to synthesizing tryptophan itself from the 5-hydroxytryptophan intermediate would require adding ethanol and water, and letting sit for 30 days this time. The next two steps would be the same as the first phase: adding HCl to make the pH = 3, and then adding NaOH to make the pH very basic at 13 for 1 hour. This phase uses the Psilocybe coprophila as the catalyst for the reaction.[216]

Serotonin taken orally does not pass into the serotonergic pathways of the central nervous system, because it does not cross the blood–brain barrier.[9] However, tryptophan and its metabolite 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), from which serotonin is synthesized, do cross the blood–brain barrier. These agents are available as dietary supplements and in various foods, and may be effective serotonergic agents.

One product of serotonin breakdown is 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), which is excreted in the urine. Serotonin and 5-HIAA are sometimes produced in excess amounts by certain tumors or cancers, and levels of these substances may be measured in the urine to test for these tumors.

Analytical chemistry

[edit]Indium tin oxide is recommended for the electrode material in electrochemical investigation of concentrations produced, detected, or consumed by microbes.[217] A mass spectrometry technique was developed in 1994 to measure the molecular weight of both natural and synthetic serotonins.[218]

History and etymology

[edit]It had been known to physiologists for over a century that a vasoconstrictor material appears in serum when blood was allowed to clot.[219] In 1935, Italian Vittorio Erspamer, working in Pavia, showed an extract from enterochromaffin cells made intestines contract. Some believed it contained adrenaline, but two years later, Erspamer was able to show it was a previously unknown amine, which he named "enteramine".[220][221] In 1948, Maurice M. Rapport, Arda Green, and Irvine Page of the Cleveland Clinic discovered a vasoconstrictor substance in blood serum, and since it was a serum agent affecting vascular tone, they named it serotonin.[222]

In 1952, enteramine was shown to be the same substance as serotonin, and as the broad range of physiological roles was elucidated, the abbreviation 5-HT of the proper chemical name 5-hydroxytryptamine became the preferred name in the pharmacological field.[223] Synonyms of serotonin include: 5-hydroxytriptamine, enteramine, substance DS, and 3-(β-aminoethyl)-5-hydroxyindole.[224] In 1953, Betty Twarog and Page discovered serotonin in the central nervous system.[225] Page regarded Erspamer's work on Octopus vulgaris, Discoglossus pictus, Hexaplex trunculus, Bolinus brandaris, Sepia, Mytilus, and Ostrea as valid and fundamental to understanding this newly identified substance, but regarded his earlier results in various models – especially those from rat blood – to be too confounded by the presence of other bioactive chemicals, including some other vasoactives.[226]

Notes

[edit]- ^ References for the functions of these receptors are available on the wikipedia pages for the specific receptor in question

References

[edit]- ^ Calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V11.02 (©1994–2011 ACD/Labs)

- ^ Mazák K, Dóczy V, Kökösi J, Noszál B (April 2009). "Proton speciation and microspeciation of serotonin and 5-hydroxytryptophan". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 6 (4): 578–590. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200800087. PMID 19353542. S2CID 20543931.

- ^ Pietra S (1958). "[Indolic derivatives. II. A new way to synthesize serotonin]". Il Farmaco; Edizione Scientifica (in Italian). 13 (1): 75–79. PMID 13524273.

- ^ Erspamer V (1952). "Ricerche preliminari sulle indolalchilamine e sulle fenilalchilamine degli estratti di pelle di Anfibio". Ricerca Scientifica. 22: 694–702.

- ^ Tammisto T (1967). "Increased toxicity of 5-hydroxytryptamine by ethanol in rats and mice". Annales Medicinae Experimentalis et Biologiae Fenniae. 46 (3): 382–384. PMID 5734241.

- ^ Jones D (2003) [1917]. Roach P, Hartmann J, Setter J (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ "Serotonin". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Serotonin". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Young SN (November 2007). "How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 32 (6): 394–399. PMC 2077351. PMID 18043762.

- ^ "Microbes Help Produce Serotonin in Gut". California Institute of Technology. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ King MW. "Serotonin". The Medical Biochemistry Page. Indiana University School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL (2009). "The expanded biology of serotonin". Annual Review of Medicine. 60: 355–366. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. PMC 5864293. PMID 19630576.

- ^ Schlienger RG, Meier CR (2003). "Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet activation: can they prevent acute myocardial infarction?". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 3 (3): 149–162. doi:10.2165/00129784-200303030-00001. PMID 14727927. S2CID 23986530.

- ^ Kling A (2013). 5-HT2A: a serotonin receptor with a possible role in joint diseases (PDF) (Thesis). Umeå Universitet. ISBN 978-91-7459-549-9.

- ^ Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, et al. (April 2015). "Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis". Cell. 161 (2): 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. PMC 4393509. PMID 25860609.

- ^ Sangare A, Dubourget R, Geoffroy H, Gallopin T, Rancillac A (October 2016). "Serotonin differentially modulates excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to putative sleep-promoting neurons of the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus" (PDF). Neuropharmacology. 109: 29–40. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.015. PMID 27238836.

- ^ Rancillac A (November 2016). "Serotonin and sleep-promoting neurons". Oncotarget. 7 (48): 78222–78223. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13419. PMC 5346632. PMID 27861160.

- ^ Vanhoutte PM (February 1987). "Serotonin and the vascular wall". International Journal of Cardiology. 14 (2): 189–203. doi:10.1016/0167-5273(87)90008-8. PMID 3818135.

- ^ a b Huser A, Rohwedder A, Apostolopoulou AA, Widmann A, Pfitzenmaier JE, Maiolo EM, et al. (2012). Zars T (ed.). "The serotonergic central nervous system of the Drosophila larva: anatomy and behavioral function". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e47518. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747518H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047518. PMC 3474743. PMID 23082175.

- ^ a b c Ramakrishna A, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA (June 2011). "Phytoserotonin: a review". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 6 (6): 800–809. Bibcode:2011PlSiB...6..800A. doi:10.4161/psb.6.6.15242. PMC 3218476. PMID 21617371.

- ^ a b Chen J, Lariviere WR (October 2010). "The nociceptive and anti-nociceptive effects of bee venom injection and therapy: a double-edged sword". Progress in Neurobiology. 92 (2): 151–183. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.006. PMC 2946189. PMID 20558236.

- ^ a b c d e Erspamer V (1966). "Occurrence of indolealkylamines in nature". 5-Hydroxytryptamine and Related Indolealkylamines. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 132–181. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-85467-5_4. ISBN 978-3-642-85469-9.

- ^ a b McGowan K, Kane A, Asarkof N, Wicks J, Guerina V, Kellum J, et al. (August 1983). "Entamoeba histolytica causes intestinal secretion: role of serotonin". Science. 221 (4612): 762–764. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..762M. doi:10.1126/science.6308760. PMID 6308760.

- ^ a b Feldman JM, Lee EM (October 1985). "Serotonin content of foods: effect on urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 42 (4): 639–643. doi:10.1093/ajcn/42.4.639. PMID 2413754.

- ^ González-Flores D, Velardo B, Garrido M, et al. (2011). "Ingestion of Japanese plums (Prunus salicina Lindl. cv. Crimson Globe) increases the urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin and total antioxidant capacity levels in young, middle-aged and elderly humans: Nutritional and functional characterization of their content". Journal of Food and Nutrition Research. 50 (4): 229–236.

- ^ Rychkov DA, Hunter S, Kovalskii VY, Lomzov AA, Pulham CR, Boldyreva EV (July 2016). "Towards an understanding of crystallization from solution. DFT studies of multi-component serotonin crystals". Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 1088: 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2016.04.027.

- ^ Naeem M, Chadeayne AR, Golen JA, Manke DR (April 2022). "Crystal structure of serotonin". Acta Crystallographica Section E. 78 (Pt 4): 365–368. Bibcode:2022AcCrE..78..365N. doi:10.1107/S2056989022002559. PMC 8983975. PMID 35492269.

- ^ Rychkov D, Boldyreva EV, Tumanov NA (September 2013). "A new structure of a serotonin salt: comparison and conformational analysis of all known serotonin complexes". Acta Crystallographica Section C. 69 (Pt 9): 1055–1061. Bibcode:2013AcCrC..69.1055R. doi:10.1107/S0108270113019823. PMID 24005521.

- ^ Mohammad-Zadeh LF, Moses L, Gwaltney-Brant SM (June 2008). "Serotonin: a review". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 31 (3): 187–199. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.00944.x. PMID 18471139.

- ^ Vaseghi S, Arjmandi-Rad S, Eskandari M, Ebrahimnejad M, Kholghi G, Zarrindast MR (February 2022). "Modulating role of serotonergic signaling in sleep and memory". Pharmacological Reports. 74 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1007/s43440-021-00339-8. PMID 34743316.

- ^ a b Kravitz EA (September 1988). "Hormonal control of behavior: amines and the biasing of behavioral output in lobsters". Science. 241 (4874): 1775–1781. Bibcode:1988Sci...241.1775K. doi:10.1126/science.2902685. PMID 2902685.

- ^ Sinclair-Wilson A, Lawrence A, Ferezou I, Cartonnet H, Mailhes C, Garel S, et al. (August 2023). "Plasticity of thalamocortical axons is regulated by serotonin levels modulated by preterm birth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 120 (33): e2301644120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12001644S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2301644120. PMC 10438379. PMID 37549297.

- ^ a b Zifa E, Fillion G (September 1992). "5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 44 (3): 401–458. PMID 1359584.

- ^ a b Srinivasan S, Sadegh L, Elle IC, Christensen AG, Faergeman NJ, Ashrafi K (June 2008). "Serotonin regulates C. elegans fat and feeding through independent molecular mechanisms". Cell Metabolism. 7 (6): 533–544. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.012. PMC 2495008. PMID 18522834.

- ^ Ramakrishna A, Ravishankar GA (November 2011). "Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 6 (11). Informa: 1720–1731. Bibcode:2011PlSiB...6.1720A. doi:10.4161/psb.6.11.17613. PMC 3329344. PMID 22041989.

- ^ Whitaker R, Cosgrove L (2015). Psychiatry Under the Influence: Institutional Corruption, Social Injury, and Prescriptions for Reform. Springer. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-137-51602-2.

- ^ Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA (August 2023). "The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence". Molecular Psychiatry. 28 (8). Nature Publishing Group: 3243–3256. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0. PMC 10618090. PMID 35854107. S2CID 250646781.

- ^ Ghaemi N (2022), Has the Serotonin Hypothesis Been Debunked?, retrieved 2 May 2023

- ^ Bortolato M, Chen K, Shih JC (2010). "The Degradation of Serotonin: Role of MAO". Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience. Vol. 21. Elsevier. pp. 203–218. doi:10.1016/s1569-7339(10)70079-5. ISBN 978-0-12-374634-4.

- ^ Matthes S, Mosienko V, Bashammakh S, Alenina N, Bader M (2010). "Tryptophan hydroxylase as novel target for the treatment of depressive disorders". Pharmacology. 85 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1159/000279322. PMID 20130443.

- ^ Prah A, Purg M, Stare J, Vianello R, Mavri J (September 2020). "How Monoamine Oxidase A Decomposes Serotonin: An Empirical Valence Bond Simulation of the Reactive Step". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 124 (38): 8259–8265. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06502. PMC 7520887. PMID 32845149.

- ^ Hannon J, Hoyer D (December 2008). "Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors". Behavioural Brain Research. 195 (1): 198–213. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020. PMID 18571247. S2CID 46043982.

- ^ a b Zhou M, Engel K, Wang J (January 2007). "Evidence for significant contribution of a newly identified monoamine transporter (PMAT) to serotonin uptake in the human brain". Biochemical Pharmacology. 73 (1): 147–154. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.008. PMC 1828907. PMID 17046718.

- ^ a b c Paulmann N, Grohmann M, Voigt JP, Bert B, Vowinckel J, Bader M, et al. (October 2009). O'Rahilly S (ed.). "Intracellular serotonin modulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells by protein serotonylation". PLOS Biology. 7 (10): e1000229. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000229. PMC 2760755. PMID 19859528.

- ^ Walther DJ, Peter JU, Winter S, Höltje M, Paulmann N, Grohmann M, et al. (December 2003). "Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet alpha-granule release". Cell. 115 (7): 851–862. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01014-6. PMID 14697203. S2CID 16847296.

- ^ Watts SW, Priestley JR, Thompson JM (May 2009). "Serotonylation of vascular proteins important to contraction". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5682. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5682W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005682. PMC 2682564. PMID 19479059.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Bortolozzi A, Díaz-Mataix L, Scorza MC, Celada P, Artigas F (December 2005). "The activation of 5-HT receptors in prefrontal cortex enhances dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 95 (6): 1597–1607. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03485.x. hdl:10261/33026. PMID 16277612. S2CID 18350703.

- ^ Moro C, Edwards L, Chess-Williams R (November 2016). "5-HT2A receptor enhancement of contractile activity of the porcine urothelium and lamina propria". International Journal of Urology. 23 (11): 946–951. doi:10.1111/iju.13172. PMID 27531585.

- ^ "Von Economo neuron – NeuronBank". neuronbank.org.[unreliable medical source?]

- ^ Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Dekeyne A, Newman-Tancredi A, Pasteau V, et al. (September 2003). "The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 306 (3): 954–964. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.051797. PMID 12750432. S2CID 18753440.

- ^ Gonzalez R, Chávez-Pascacio K, Meneses A (September 2013). "Role of 5-HT5A receptors in the consolidation of memory". Behavioural Brain Research. 252: 246–251. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.051. PMID 23735322. S2CID 140204585.

- ^ Nautiyal KM, Hen R (2017). "Serotonin receptors in depression: from A to B". F1000Research. 6: 123. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9736.1. PMC 5302148. PMID 28232871.

- ^ Frazer A, Hensler JG (1999). "Understanding the neuroanatomical organization of serotonergic cells in the brain provides insight into the functions of this neurotransmitter". In Siegel GJ, Agranoff, Bernard W, Fisher SK, Albers RW, Uhler MD (eds.). Basic Neurochemistry (Sixth ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-397-51820-3.

In 1964, Dahlstrom and Fuxe (discussed in [2]), using the Falck-Hillarp technique of histofluorescence, observed that the majority of serotonergic soma are found in cell body groups, which previously had been designated as the Raphe nuclei.

- ^ Binder MD, Hirokawa N (2009). encyclopedia of neuroscience. Berlin: Springer. p. 705. ISBN 978-3-540-23735-8.

- ^ The raphe nuclei group of neurons are located along the brain stem from the labels 'Mid Brain' to 'Oblongata', centered on the pons. (See relevant image.)

- ^ Müller CP, Jacobs BL, eds. (2009). Handbook of the behavioral neurobiology of serotonin (1st ed.). London: Academic. pp. 51–59. ISBN 978-0-12-374634-4.

- ^ Passos AD, Herculano AM, Oliveira KR, de Lima SM, Rocha FA, Freitas HR, et al. (October 2019). "Regulation of the Serotonergic System by Kainate in the Avian Retina". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 39 (7): 1039–1049. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00701-8. PMID 31197744. S2CID 189763144.

- ^ Sommer C (2009). "Serotonin in Pain and Pain Control". In Müller CP, Jacobs BL (eds.). Handbook of the behavioral neurobiology of serotonin (1st ed.). London: Academic. pp. 457–460. ISBN 978-0-12-374634-4.

- ^ Hensler JG (2009). "Serotonin in Mode and Emotions". In Müller CP, Jacobs BL (eds.). Handbook of the behavioral neurobiology of serotonin (1st ed.). London: Academic. pp. 367–399. ISBN 978-0-12-374634-4.

- ^ Andrews PW, Bharwani A, Lee KR, Fox M, Thomson JA (April 2015). "Is serotonin an upper or a downer? The evolution of the serotonergic system and its role in depression and the antidepressant response". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 51: 164–188. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.018. PMID 25625874. S2CID 23980182.

- ^ Stahl SM, Mignon L, Meyer JM (March 2009). "Which comes first: atypical antipsychotic treatment or cardiometabolic risk?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 119 (3): 171–179. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01334.x. PMID 19178394. S2CID 24035040.

- ^ Buckland PR, Hoogendoorn B, Guy CA, Smith SK, Coleman SL, O'Donovan MC (March 2005). "Low gene expression conferred by association of an allele of the 5-HT2C receptor gene with antipsychotic-induced weight gain". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (3): 613–615. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.613. PMID 15741483.

- ^ Holmes MC, French KL, Seckl JR (June 1997). "Dysregulation of diurnal rhythms of serotonin 5-HT2C and corticosteroid receptor gene expression in the hippocampus with food restriction and glucocorticoids". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (11): 4056–4065. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04056.1997. PMC 6573558. PMID 9151722.

- ^ Leibowitz SF (1990). "The role of serotonin in eating disorders". Drugs. 39 (Suppl 3): 33–48. doi:10.2165/00003495-199000393-00005. PMID 2197074. S2CID 8612545.

- ^ McGuire, Michael (2013) "Believing, the neuroscience of fantasies, fears, and confictions" (Prometius Books)

- ^ Caspi N, Modai I, Barak P, Waisbourd A, Zbarsky H, Hirschmann S, et al. (March 2001). "Pindolol augmentation in aggressive schizophrenic patients: a double-blind crossover randomized study". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 16 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1097/00004850-200103000-00006. PMID 11236069. S2CID 24822810.

- ^ Ito Z, Aizawa I, Takeuchi M, Tabe M, Nakamura T (December 1975). "[Proceedings: Study of gastrointestinal motility using an extraluminal force transducer. 6. Observation of gastric and duodenal motility using synthetic motilin]". Nihon Heikatsukin Gakkai Zasshi. 11 (4): 244–246. PMID 1232434.

- ^ Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, et al. (November 1996). "Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region". Science. 274 (5292): 1527–1531. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1527L. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. PMID 8929413. S2CID 35503987.

- ^ Beattie DT, Smith JA (May 2008). "Serotonin pharmacology in the gastrointestinal tract: a review". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 377 (3): 181–203. doi:10.1007/s00210-008-0276-9. PMID 18398601. S2CID 32820765.

- ^ Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- ^ de Wit R, Aapro M, Blower PR (September 2005). "Is there a pharmacological basis for differences in 5-HT3-receptor antagonist efficacy in refractory patients?". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 56 (3): 231–238. doi:10.1007/s00280-005-1033-0. PMID 15838653. S2CID 27576150.

- ^ a b Lauweryns JM, Cokelaere J, Theunynck P (April 1973). "Serotonin producing neuroepithelial bodies in rabbit respiratory mucosa". Science. 180 (4084): 410–413. Bibcode:1973Sci...180..410L. doi:10.1126/science.180.4084.410. PMID 4121716. S2CID 2809307.

- ^ Pastor LM, Ballesta J, Perez-Tomas R, Marin JA, Hernandez F, Madrid JF (June 1987). "Immunocytochemical localization of serotonin in the reptilian lung". Cell and Tissue Research. 248 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 713–715. doi:10.1007/bf00216504. PMID 3301000. S2CID 9871728.

- ^ a b Sonstegard KS, Mailman RB, Cheek JM, Tomlin TE, DiAugustine RP (November 1982). "Morphological and cytochemical characterization of neuroepithelial bodies in fetal rabbit lung. I. Studies of isolated neuroepithelial bodies". Experimental Lung Research. 3 (3–4): 349–377. doi:10.3109/01902148209069663. PMID 6132813.

- ^ Chang W, Kanda H, Ikeda R, Ling J, DeBerry JJ, Gu JG (September 2016). "Merkel disc is a serotonergic synapse in the epidermis for transmitting tactile signals in mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (37): E5491–E5500. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E5491C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1610176113. PMC 5027443. PMID 27573850.

- ^ Frost M, Andersen TE, Yadav V, Brixen K, Karsenty G, Kassem M (March 2010). "Patients with high-bone-mass phenotype owing to Lrp5-T253I mutation have low plasma levels of serotonin". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 25 (3): 673–675. doi:10.1002/jbmr.44. PMID 20200960. S2CID 24280062.

- ^ Rosen CJ (February 2009). "Breaking into bone biology: serotonin's secrets". Nature Medicine. 15 (2): 145–146. doi:10.1038/nm0209-145. PMID 19197289. S2CID 5489589.

- ^ Mödder UI, Achenbach SJ, Amin S, Riggs BL, Melton LJ, Khosla S (February 2010). "Relation of serum serotonin levels to bone density and structural parameters in women". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 25 (2): 415–422. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090721. PMC 3153390. PMID 19594297.

- ^ Frost M, Andersen T, Gossiel F, Hansen S, Bollerslev J, van Hul W, et al. (August 2011). "Levels of serotonin, sclerostin, bone turnover markers as well as bone density and microarchitecture in patients with high-bone-mass phenotype due to a mutation in Lrp5". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 26 (8): 1721–1728. doi:10.1002/jbmr.376. PMID 21351148.

- ^ Kode A, Mosialou I, Silva BC, Rached MT, Zhou B, Wang J, et al. (October 2012). "FOXO1 orchestrates the bone-suppressing function of gut-derived serotonin". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 122 (10): 3490–3503. doi:10.1172/JCI64906. PMC 3461930. PMID 22945629.

- ^ Yadav VK, Balaji S, Suresh PS, Liu XS, Lu X, Li Z, et al. (March 2010). "Pharmacological inhibition of gut-derived serotonin synthesis is a potential bone anabolic treatment for osteoporosis". Nature Medicine. 16 (3): 308–312. doi:10.1038/nm.2098. PMC 2836724. PMID 20139991.

- ^ Sugisawa E, Takayama Y, Takemura N, Kondo T, Hatakeyama S, Kumagai Y, et al. (August 2020). "RNA Sensing by Gut Piezo1 Is Essential for Systemic Serotonin Synthesis". Cell. 182 (3): 609–624.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.022. PMID 32640190.

- ^ Ozanne SE, Hales CN (January 2004). "Lifespan: catch-up growth and obesity in male mice". Nature. 427 (6973): 411–412. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..411O. doi:10.1038/427411b. PMID 14749819. S2CID 40256021.

- ^ Lewis DS, Bertrand HA, McMahan CA, McGill HC, Carey KD, Masoro EJ (October 1986). "Preweaning food intake influences the adiposity of young adult baboons". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 78 (4): 899–905. doi:10.1172/JCI112678. PMC 423712. PMID 3760191.

- ^ Hahn P (July 1984). "Effect of litter size on plasma cholesterol and insulin and some liver and adipose tissue enzymes in adult rodents". The Journal of Nutrition. 114 (7): 1231–1234. doi:10.1093/jn/114.7.1231. PMID 6376732.

- ^ Popa D, Léna C, Alexandre C, Adrien J (April 2008). "Lasting syndrome of depression produced by reduction in serotonin uptake during postnatal development: evidence from sleep, stress, and behavior". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (14): 3546–3554. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4006-07.2008. PMC 6671102. PMID 18385313.

- ^ Maciag D, Simpson KL, Coppinger D, Lu Y, Wang Y, Lin RC, et al. (January 2006). "Neonatal antidepressant exposure has lasting effects on behavior and serotonin circuitry". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300823. PMC 3118509. PMID 16012532.