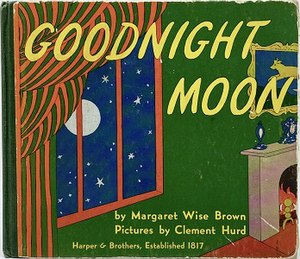

Goodnight Moon

Book cover | |

| Author | Margaret Wise Brown |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Clement Hurd |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

Publication date | September 3, 1947 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 32pp |

| ISBN | 0-06-443017-0 |

| OCLC | 299277 |

| [E] 21 | |

| LC Class | PZ7.B8163 Go 1997 |

| Preceded by | The Runaway Bunny |

| Followed by | My World |

Goodnight Moon is an American children's book written by Margaret Wise Brown and illustrated by Clement Hurd. It was published on September 3, 1947, and is a highly acclaimed bedtime story.

This book is the second in Brown and Hurd's "classic series," which also includes The Runaway Bunny and My World. The three books have been published together as a collection titled Over the Moon.[1]

Background

[edit]In 1935,[2] author Margaret Wise Brown enrolled at the Bank Street Experimental School[3] in New York, NY.[2] At Bank Street, Brown studied childhood development alongside the school’s founder, Lucy Sprague Mitchell,[2] who believed that children preferred stories about everyday topics rather than fantasies.[2] Mitchell's ideas[2] combined with Brown's observance of what children enjoyed[3] formed the foundation for Brown's writing, including the familiar world depicted in Goodnight Moon.[4]

In 1945, the idea for Goodnight Moon appeared to Margaret Wise Brown in a dream.[5] She wrote down the story in the morning, with the original title of the book being Goodnight Room.[5] Brown gave illustrator Clement Hurd very little direction on the illustrations,[2] and the characters in Goodnight Moon are depicted as rabbits because Hurd was better at drawing rabbits than humans.[2] This was among several decisions made regarding the illustrations over the course of the book's creation.[2] Other revisions include replacing a framed map on the wall with a scene from The Runaway Bunny and blurring the udder of the "cow that jumped over the moon."[2]

Publication history

[edit]Illustrator Clement Hurd said in 1983 that initially the book was to be published using the pseudonym "Memory Ambrose" for Brown, with his illustrations credited to "Hurricane Jones".[6]

Goodnight Moon had poor initial sales: only 6,000 copies were sold upon initial release in the fall of 1947.[citation needed] Anne Carroll Moore, the influential children's librarian at the New York Public Library (NYPL), regarded it as "overly sentimental".[citation needed] The NYPL and other libraries did not acquire it at first.[7] During the post-World War II Baby Boom years, it slowly became a bestseller. Annual sales grew from about 1,500 copies in 1953 to almost 20,000 in 1970;[7] by 1990, the total number of copies sold exceeded four million.[8] As of 2007[update], the book sells about 800,000 copies annually,[9] and by 2017 had cumulatively sold an estimated 48 million copies.[10] Goodnight Moon has been translated into Ukrainian, Armenian, Spanish, French, Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, Catalan, Hebrew, Brazilian Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, Korean, Hmong, and German.[11][12]

In 1952, at the age of 42, Margaret Wise Brown died following a routine operation, and did not live to see the success of her book.[2] Brown bequeathed the royalties to the book (among many others) to Albert Clarke, who was the nine-year-old son of a neighbor when Brown died. Clarke, whose rights to the book earned him millions of dollars, said that Brown was his mother, a claim others dismiss.[13]

In 2005, publisher HarperCollins digitally altered the photograph of illustrator Hurd, which had been on the book for at least twenty years, to remove a cigarette. HarperCollins' editor-in-chief for children's books, Kate Jackson, said: "It is potentially a harmful message to very young [children]." HarperCollins had the reluctant permission of Hurd's son, Thacher Hurd, but the younger Hurd said the photo of Hurd with his arm and fingers extended, holding nothing, "looks slightly absurd to me".[14] HarperCollins has said it will likely replace the picture with a different, unaltered photo of Hurd in future editions.[needs update][citation needed]

Other editions

[edit]In addition to several octavo and duodecimo paperback editions, Goodnight Moon is available as a board book and in "jumbo" edition designed for use with large groups.[citation needed]

- 1991, US, HarperFestival ISBN 0-694-00361-1, publication date September 30, 1991, board book.[citation needed]

- 1997, US, HarperCollins ISBN 0-06-027504-9, publication date February 28, 1997, Hardback 50th anniversary edition.[citation needed]

- 2007, US, HarperCollins ISBN 0-694-00361-1, publication date January 23, 2007, Board book 60th anniversary edition.[citation needed]

In 2008, Thacher Hurd used his father's artwork from Goodnight Moon to produce Goodnight Moon 123: A Counting Book. In 2010, HarperCollins used artwork from the book to produce Goodnight Moon's ABC: An Alphabet Book.[citation needed]

In 2015, Loud Crow Interactive Inc. released a Goodnight Moon interactive app.[citation needed]

Synopsis

[edit]The text is a rhyming poem, describing an anthropomorphic bunny's bedtime ritual of saying "good night" to various inanimate and living objects in the bunny's bedroom: a red balloon, a pair of socks, the bunny's dollhouse, a bowl of mush, a woman (an older female anthropomorphic rabbit, possibly his mother or an adult caretaker rabbit) who apparently says "hush", and two kittens, among others; despite the kittens, a mouse is present in each spread.[15] The book begins at 7:00 PM, and ends at 8:10 PM, with each spread being spaced 10 minutes apart, as measured by the two clocks in the room, and reflected (improbably)[16] in the rising moon.[17] The illustrations alternate between 2-page black-and-white spreads of objects and 2-page color spreads of the room, like the other books in the series (a common cost-saving technique at the time).[15]

Allusions and references

[edit]Goodnight Moon contains a number of references to Brown and Hurd's The Runaway Bunny, and to traditional children's literature. For example, the room of Goodnight Moon generally resembles the next-to-last spread of The Runaway Bunny, where the little bunny becomes a little boy and runs into a house, and the mother bunny becomes the little boy's mother; shared details include the fireplace and the painting by the fireplace of "The Cow Jumping Over the Moon", though other details differ (the colors of the walls and floor are switched, for instance). The painting is itself a reference to the nursery rhyme "Hey Diddle Diddle," where a cow jumps over the moon.[18] However, when reprinted in Goodnight Moon, the udder was reduced to an anatomical blur to avoid the controversy that E.B. White's Stuart Little had undergone when published in 1945.[19] The painting of three bears, sitting in chairs, alludes to "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" (originally "The Story of the Three Bears"),[18] which also contains a copy of the cow jumping over the moon painting. The other painting in the room, which is never explicitly mentioned in the text, portrays a bunny fly-fishing for another bunny, using a carrot as bait. This picture is also a reference to The Runaway Bunny, where it is the first colored spread, when the mother says that if the little bunny becomes a fish, she will become a fisherman and fish for him. The top shelf of the bookshelf, below the Runaway Bunny painting, holds an open copy of The Runaway Bunny, and there is a copy of Goodnight Moon on the nightstand.

A telephone is mentioned early in the book. The primacy of the reference to the telephone indicates that the bunny is in his mother's room and his mother's bed.[20]

Literary significance and reception

[edit]In a 2007 online poll, the National Education Association listed the book as one of its "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children."[21] In 2012 it was ranked number four among the "Top 100 Picture Books" in a survey published by School Library Journal.[22]

From the time of its publication in 1947 until 1972, the book was "banned" by the New York Public Library due to the then-head children's librarian Anne Carroll Moore's hatred of the book.[23] Moore was considered a top taste-maker and arbiter of children's books not only in the New York Public Library, but for libraries nationwide in the United States, even well past her official retirement.[24][23] The book was stocked on the library's shelves only in 1972, at the time of the 25th anniversary of its publication.[23] It did not appear on the NYPL's 2020 list of the 10 most-checked-out books in the library's history.[24]

Author Susan Cooper writes that the book is possibly the only "realistic story" to gain the universal affection of a fairy-tale, although she also noted that it is actually a "deceptively simple ritual" rather than a story.[25]

Writer Ellen Handler Spitz suggests that Goodnight Moon teaches "young children that life can be trusted, that life has stability, reliability, and durability."[26]

Writer Robin Bernstein suggests that Goodnight Moon is popular largely because it helps parents put children to sleep.[27] Bernstein distinguishes between "going-to-bed" books that help children sleep and "bedtime books" that use nighttime as a theme. Goodnight Moon, Bernstein argues, is both a bedtime book and a going-to-bed book.[28]

According to The Daily News (Halifax) writer Cathy MacDonald, when Goodnight Moon was first published, it was considered controversial.[5] This was because Goodnight Moon did not teach children anything,[5] and Goodnight Moon did not "take" children anywhere, as the entire story takes place in only one room.[5]

New Yorker writer Rosemary C. Benet called Goodnight Moon a "hypnotic bedtime litany".[2]

Regarding Goodnight Moon, The Christian Science Monitor wrote that "a book for little children which creates an atmosphere of peace and calm is something for which to be thankful."[2]

Analysis

[edit]In his article Bedtime Books, the Bedtime Story Ritual, and Goodnight Moon, Daniel Pereira analyzes the function of Goodnight Moon as a "bedtime book" that is not only beneficial to children at bedtime, but is beneficial to parents as well.[29] Pereira first defines a "bedtime book" as a book that both "represents" bedtime and is about bedtime, and is meant to be read by a parent and child together.[29] Pereira further argues that bedtime books such as Goodnight Moon serve parental interests since they help parents carry out their duty of being an "entertainer, educator, enchanter"[29] at bedtime while also maintaining a sense of independence between the child and the parent.[29] Pereira analyzes the effectiveness of Goodnight Moon's illustrations in assisting parents at bedtime through discussing Joseph Stanton's evaluation of the role of the "old lady", who is treated as another "feature of the landscape"[29] rather than as a character herself.[29] Stanton notes that the objectification of the old lady contributes to a sense of independence in the child, who lacks a true parental figure in the "great green room".[29] Pereira asserts that despite this objectification, the old lady still conveys a message when she whispers "hush".[29] He notes that in doing so, the old lady "delivers the parent's bedtime message for them,"[29] which reminds the child reader to be quiet.[29]

In the article 'Goodnight Nobody': Comfort and the Vast Dark in the Picture-Poems of Margaret Wise Brown and Her Collaborators, author Joseph Stanton discusses a motif present in Goodnight Moon that he refers to as "child-alone-in-the-wide-world".[30] According to Stanton, this motif is present in much of Brown's work and is characterized by a child character finding resolution in being left alone.[30] Further contributing to this motif, Stanton argues that the child is at the center of both the words and the illustrations in Goodnight Moon due to a lack of any parental figure.[30] He states that the voice in Goodnight Moon is not the child's voice, but rather an omniscient voice that knows and understands what the child sees.[30] Additionally, Stanton comments that each illustration focuses on what the child is looking at, which corresponds to what is being named in each scene.[30]

In his article 'Goodnight Moon' was once banned: Classic children's book marks 75th anniversary, Jim Beckerman presents analysis about why children enjoy Goodnight Moon.[3] Beckerman references professor Julie Rosenthal's point that Goodnight Moon acts as a "scavenger hunt"[3] for children, as they are able to search the illustrations for each object mentioned in the book.[3] Beckerman also mentions some of professor April Patrick's ideas, such as how the rhyming scheme fascinates children,[3] as well as how children feel comfort in reading a book about real things.[3]

Animated adaptation

[edit]In 1985, Weston Woods released a filmstrip adaptation of the book.[31]

On July 15, 1999, Goodnight Moon was announced as a 26-minute animated family video special/documentary, which debuted on HBO Family in December of that year,[32] and was released on VHS on April 15, 2000, and DVD in 2005, in the United States. The special features an animated short of Goodnight Moon, narrated by Susan Sarandon, along with six other animated segments of children's bedtime stories and lullabies with live-action clips of children reflecting on a series of bedtime topics in between, a reprise of Goodnight Moon at the end, and the Everly Brothers' "All I Have To Do Is Dream" playing over the closing credits. The special is notable for its post-credits clip, which features a boy being interviewed about dreams but stumbling over his sentence, which soon became a meme in 2011 when it was uploaded on YouTube. He was referencing a line from the 1997 Disney animated film Hercules.[33] The boy's identity was unknown until July 2021, when he came forward as Joseph Cirkiel in a video interview with Youtuber wavywebsurf.[34]

Here are the other tales and lullabies featured in the video:

- Lullaby: "Hit the Road to Dreamland" sung by Tony Bennett (This lullaby plays in the opening credits, right before Goodnight Moon.)

- Lullaby: "Hush, Little Baby" sung by Lauryn Hill

- Story: There's a Nightmare in My Closet narrated by Billy Crystal

- Story: Tar Beach narrated by Natalie Cole

- Lullaby: "Brahms' Lullaby" sung by Aaron Neville

- Lullaby: "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" sung by Patti LaBelle

Musical adaptation

[edit]In 2012, American composer Eric Whitacre obtained the copyright holder's permission to set the words to music. He did so initially for a soprano, specifically his then wife Hila Plitmann, with harp and string orchestra. He subsequently arranged it for soprano and piano, SSA (two soprano lines plus alto; commissioned by the National Children's Chorus), and SATB (commissioned by a consortium of choirs).[35][36][37]

Exhibit adaptation

[edit]In 2006, an exhibit titled "From Goodnight Moon to Art Dog: The World of Clement, Edith and Thacher Hurd" was on display at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island.[38] This exhibit featured 3-D displays of Clement Hurd's artwork, as well as artwork from his wife, Edith Hurd, and his son, Thacher Hurd.[38] Included in the displays was the "great green room" scene from Goodnight Moon.[38] Providence was the exhibit's final stop in the United States.[38] The exhibit had also featured shows in Vermont, Michigan, Florida and South Carolina.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Margaret Wise and Clement Hurd. Over the Moon: A Collection of First Books (HarperCollins, 2006).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Marcus, Leonard. "Awakened by the Moon: a new biography of Margaret Wise Brown presents a revealing portrait of the author of Goodnight Moon and more than 100 other books for children.", vol. 238, no. 33, 1991, pp. 16+. Gale Literature Resource Center; Gale.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beckerman, Jim. "'Goodnight Moon' was once banned: Classic children's book marks 75th anniversary." The News Journal, 2022. ProQuest Central.

- ^ Mills, Nicolaus. "We've Been Saying Goodnight to That Moon for 70 Years: It doesn't have a plot or much of a main character, and it all takes place inside one room. But 'Goodnight Moon' has been enchanting us for generations, and it never gets old." The Daily Beast, ProQuest Central, Research Library, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e MacDonald, Cathy. "That great green room: Margaret Wise Brown's children's classic turns 50." The Daily News (Halifax), 1997, pp. 64.

- ^ Hurd, Clement. "Remembering Margaret Wise Brown." Horn Book Magazine Vol. 59 (5). October 1983. 553-560. 552.

- ^ a b Meagan Flynn. "Who could hate 'Goodnight Moon'? This powerful New York librarian." The Washington Post. via San Francisco Chronicle. January 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Writer's Almanac for the week of May 21, 2007". Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Adcock, Joe. "Turning a tiny book into a musical? No problem," Seattle Post-Intelligencer (January 11, 2007).

- ^ Crawford, Amy (January 17, 2017). "The Surprising Ingenuity Behind "Goodnight Moon"". Smithsonian. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Robin Bernstein, "'You Do it!': Going-to-Bed Books and the Scripts of Children's Literature," PMLA, Volume 135 , Issue 5 , October 2020 , pp. 877 - 894

- ^ "Buenas noches, luna". shop.scholastic.com.

- ^ Prager, Joshua (September 8, 2000). "Runaway Money". Wall Street Journal. p. A1. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (November 17, 2005). "'Goodnight Moon,' Smokeless Version". New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2005.

- ^ a b Andrea (November 14, 2009). "Things You Might Not Have Known About Goodnight Moon". Archived from the original on January 5, 2021.

- ^ Dr Chad Orzel (October 12, 2010). "The Astrophysics of Bedtime Stories".

- ^ Chuck Bueter (1997). "Good(night) Moons Rising". GLPA Proceedings. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Leanne Barrett (January 25, 2019). "Review: Goodnight Moon". Kids' Book Review. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019.

- ^ Marcus, Leonard S. Making of Goodnight Moon (New York: HarperTrophy, 1997), p. 21.

- ^ Pearson, Claudia. Have a Carrot: Oedipal Theory and Symbolism in Margaret Wise Brown's Runaway Bunny Trilogy. Look Again Press (2010). ISBN 978-1-4524-5500-6.

- ^ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (July 6, 2012). "Top 100 Picture Books Poll Results". "A Fuse #8 Production". Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c Kois, Dan (January 13, 2020). "How One Librarian Tried to Squash Goodnight Moon". Slate Magazine. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Flynn, Meagan. "Who could hate 'Goodnight Moon'? This powerful New York librarian". Washington Post. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Susan (1981). Betsy Hearne; Marilyn Kay (eds.). Celebrating Children's Books: Essays on Children's Literature in Honor of Zena Sutherland. New York: Lathrop, Lee, and Shepard Books. pp. 15. ISBN 0-688-00752-X.

- ^ Spitz, Ellen Handler. Inside Picture Books (Yale University Press, 2000), p. 34.

- ^ Bernstein, Robin (2020). ""'You Do It!': Going-to-Bed Books and the Scripts of Children's Literature"". PMLA. 135 (5): 877–894. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ Bernstein, Robin (October 2020). ""'You Do It!': Going-to-Bed Books and the Scripts of Children's Literature"". PMLA. 145 (5): 878.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pereira, Daniel. "Bedtime Books, the Bedtime Story Ritual, and Goodnight Moon." Children's Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 2, 2019, pp. 156-172. ProQuest Central, Research Library.

- ^ a b c d e Stanton, Joseph. "'Goodnight Nobody': Comfort and the Vast Dark in the Picture-Poems of Margaret Wise Brown and Her Collaborators." Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 14, 1990, pp. 66-76. Gale Literature Resource Center; Gale.

- ^ Ephemera, Uncommon (1984). "Sound Filmstrip: "Goodnight Moon" (Weston Woods Studios #298, 1984)". Internet Archive. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ Time Warner (July 15, 1999). "Fairy Tales, Bedtime Classics and Other Magical Stories Lead HBO's Fall Family Programming Lineup". Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Know Your Meme. "Have You Ever Had A Dream Like This?". Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: I FOUND THE DREAM KID! - Have You Ever Had A Dream Kid Interview, July 28, 2021, retrieved July 28, 2021

- ^ "Goodnight Moon – Music Catalog". Eric Whitacre. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ "Eric Whitacre: Water Night". Presto Music. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ "Eric Whitacre". New York Concert Review, Inc. April 20, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Exhibit based on beloved children's book opens at Rhode Island museum: [Final Edition]." North Bay Nugget, 2006. ProQuest Central.