Campus sexual assault

The examples and perspective in this deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2022) |

Campus sexual assault is the sexual assault, including rape, of a student while attending an institution of higher learning, such as a college or university.[1] The victims of such assaults are more likely to be female, but any gender can be victimized.[2] Estimates of sexual assault, which vary based on definitions and methodology, generally find that somewhere between 19–27% of college women and 6–8% of college men are sexually assaulted during their time in college.[3][4][5]

A 2007 survey by the National Institute of Justice found that 19.0% of college women and 6.1% of college men experienced either sexual assault or attempted sexual assault since entering college.[6] In the University of Pennsylvania Law Review in 2017, D. Tuerkheimer reviewed the literature on rape allegations, and reported on the problems surrounding the credibility of rape victims, and how that relates to false rape accusations. She pointed to national survey data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicates 1 in every 5 women and 1 in 71 men will be raped during their lifetime at some point. Despite the prevalence of rape, Tuerkheimer reported that law enforcement officers often default to disbelief about an alleged rape. This documented prejudice leads to reduced investigation and criminal justice outcomes that are faulty compared to other crimes. Tuerkheimer says that women face "credibility discounts" at all stages of the justice system, including from police, jurors, judges, and prosecutors. These credibility discounts are especially pronounced when the accuser is acquainted with the accused, and the vast majority of rapes fall into this category.[7] The U.S. Department of Justice estimated from 2005 to 2007 that about 2% of victims who were raped while incapacitated (from drugs, alcohol, or other reasons) reported the rape to the police, compared to 13% of victims who experienced physically forced sexual assault.[6]

In response to charges that schools have poorly supported women who have reported sexual assaults, in 2011 the United States Department of Education issued a "Dear Colleague" letter to universities advising academic institutions on various methods intended to reduce incidents of sexual assault on campuses.[8] Some legal experts have raised concerns about risks of abuses against the accused.[9] Following changes to disciplinary processes, lawsuits have been filed by men alleging bias and/or violations of their rights.[10]

Measures

[edit]There is currently no evidence that women who attend college are at a higher risk of being sexually assaulted than women of the same age who do not attend college.[11] A review of the published research in 2017 found that about 1 in 5 women was "a reasonably accurate average across women and campuses" for the percentage of women who are sexually assaulted during their time in college.[12]

Studies that have examined sexual assault experiences among college students in western countries other than the U.S. have found results similar to those found by American researchers. A 1993 study of a nationally representative sample of Canadian College students found that 28% of women had experienced some form of sexual assault in the preceding year, and 45% of women had experienced some form of sexual assault since entering college.[13] A 1991 study of 347 undergraduates in New Zealand found that 25.3% had experienced rape or attempted rape, and 51.6% had experienced some form of sexual victimization.[14] A 2011 study of students in the United Kingdom found that 25% of women had experienced some type of sexual assault while attending university and 7% of women had experienced rape or attempted rape as college students.[15]

Reporting

[edit]Research consistently shows that the majority of rape and other sexual assault victims do not report their attacks to law enforcement.[16][17][18] The majority of women who are sexually assaulted do not report because of various reasons surrounding embarrassment and shame.[19] In order to encourage those in need of support/guidance to reach out for help, the stigma encompassing sexual assault must end. As a result of non-reporting, researchers generally rely on surveys to measure sexual assault. Research estimates that between 10%[3] and 29%[20] of women are a victim of rape or attempted rape since starting college. The National Crime Victimization Survey estimates that 6.1 sexual assaults occur per 1,000 students per year.[21] However, this source is generally believed by researchers to be a significant underestimate of the number of sexual assaults.[22] Methodological differences, such as the method of survey administration, the definition of rape or sexual assault used, the wording of questions, and the time period studied contribute to these disparities.[20] There is currently no consensus on the best way to measure rape and sexual assault.[22]

On campuses, it has been found that alcohol is a prevalent issue in regards to sexual assault. It has been estimated that 1 in 5 women experience an assault, and of those women, 50–75% have had either the attacker, the woman, or both, consume alcohol prior to the assault.[23] Not only has it been a factor in the rates of sexual assault on campus, but because of the prevalence, assaults are also being affected specifically by the inability to give consent when intoxicated and bystanders not knowing when to intervene due to their own intoxication or the intoxication of the victim.[23][24]

In 1995, the CDC replicated part of this study with 8,810 students on 138 college campuses. They examined rape only and did not look at attempted rape. They found that 20% of women and 4% of men had experienced rape in the course of her or his lifetime.[25][26]

If someone wanted to reach out for help privately, there are many call hotlines available to receive support anonymously and confidentially. The nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization is RAINN (the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network). RAINN provides support and guidance to survivors in many ways.[27]

College campuses are also required to provide support to any students who have experienced sexual assault under Title IX laws. "The Women's Rights Project, in collaboration with Students Active For Ending Rape (SAFER) a national nonprofit that empowers students to hold colleges accountable for sexual assault in their communities has put together the fact sheet, podcast series, and other resources on this page to get the word out to student activists about how they can use Title IX as an effective tool for change."[28] Because of this students can not be turned away from support services provided by their college or university. This allows survivors to receive the required support following their assault.

Criticism

[edit]Some popular commentators, such as Stuart Taylor Jr., have argued that many of the surveys used to measure sexual assault are invalid because they are more likely to be taken by sexual assault victims. He also said that extrapolating the number of people who said that they had reported their rape to their school in the past year resulted in 44,000 annual reports of rape when in reality there are only 5,000 reports of sexual assault of all types (including rape) per year to universities. He also complained that the definition of sexual assault used in the surveys was broader than the one defined by the law and that the term "sexual assault" or "rape" was not used in the survey.[29]

Explanations

[edit]There are three broad approaches used to explain sexual assault.[30]

The first approach, "individual determinants", stems from the psychological perspective of rape. This approach views campus sexual assault as primarily the result of individual characteristics possessed by either the perpetrator and/or the victim. For example, Malamuth & Colleagues identified individual characteristics of hostile masculinity and impersonal sexual behavior as critical predictors of sexual aggression against women. Their psychological model states that men who display hostile masculinity traits (e.g. a desire to control/dominate women and an insecure, hypersensitive, and distrustful orientation toward women) and impersonal sexual behavior (e.g. an emotionally detached, promiscuous, and non-committal orientation towards sexual relations) are more likely to support the use of violence against women and engage in sexual assault. Their findings have been replicated in college student samples and non-student adult samples (Malamuth et al., 1991; Malamuth et al., 1993). Further, narcissistic entitlement and trait aggression have been identified as major individual risk factors for rape (LeBreton et al., 2013). The General desire or need for sex, contrary to popular opinion, is not significantly associated with sexual assault, indicating that sexual assault is an act of dominance rather than sexual gratification (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004). In regards to victims, white women, first-year students, non-students on college campuses, prior victims, and women who are more sexually active are more vulnerable to being sexually assaulted.[31]

The rape culture approach stems from second-wave feminism[32] and focuses on how rape is pervasive and normalized due to societal attitudes about gender and sexuality.[33]

The third approach to explaining rape identifies the contexts in which that rape and sexual assault occur.[34] This approach suggests that, although rape culture is a factor to why sexual assault occurs, it is also the characteristics of its setting that can increase vulnerability. For instance, practices, rules, distribution or resources, and the ideologies of the university or college can promote unhealthy beliefs about gender and can in turn contribute to campus sexual assault.[30] Fraternities are known for hosting parties in which binge drinking and casual sex are encouraged, which increase the risk of sexual assault.[35]

Characteristics

[edit]Perpetrator demographics

[edit]Research by David Lisak found that serial rapists account for 90% of all campus rapes[36] with an average of six rapes each.[37][38] A 2015 study of male students led by Kevin Swartout at Georgia State University found that four out of five perpetrators did not fit the profile of serial predators.[39]

Of the 1,084 respondents to a 1998 survey at Liberty University, 8.1% of males and 1.8% of females reported perpetrating unwanted sexual assault.[40] According to Carol Bohmer and Andrea Parrot in "Sexual Assault on Campus" males are more likely to commit a sexual assault if they choose to live in an all-male residency when co-ed housing is available.[41]

Both athletic males and fraternities have higher rates of sexual assault.[41] Student-athletes commit one-third of all campus sexual assaults at a rate six times higher than non-athletes.[42] A study conducted by the NASPA in 2007 and 2009 suggests, "that fraternity members are more likely than non-fraternity members to commit rape".[43]

In another article by Antonia Abby, she found that there are certain characteristics that male perpetrators that put them at risk of committing sexual assault. As she stresses perpetrators vary "but many show a lack of concern for other people, scoring high on narcissism and low on empathy. Many have high levels of anger in general well as hostility toward women; they are suspicious of women's motives, believe common rape myths, and have a sense of entitlement about sex".[44] Also, males on athletic teams are more likely to commit an assault after a game. The commonality between the two instances is the involvement of alcohol. Assailants are not limited to these two situations however there can also be a connection made in regards to their status in school.[45]

Victim demographics

[edit]Research of American college students suggests that white women, prior victims, first-year students, and more sexually active women are the most vulnerable to sexual assault.[30] Women who have been sexually assaulted prior to entering college are at a higher risk of experiencing sexual assault in college.[46] Another study shows that white women are more likely than non-white women to experience rape while intoxicated, but less likely to experience other forms of rape. It has been found that "the role of party rape in the lives of white college women is substantiated by recent research that found that 'white women were more likely [than non-white women] to have experienced rape while intoxicated and less likely to experience other rape.'"[30] This high rate of rape while intoxicated accounts for white women reporting a higher overall rate of sexual assault than non-white women, although further research is needed into racial differences and college party organization.[30] Regardless of race, the majority of victims know the assailant. Black women in America are more likely to report sexual assault that has been perpetrated by a stranger.[47] Victims of rape are mostly between 10 and 29 years old, while perpetrators are generally between 15 and 29 years old.[48] Nearly 60% of rapes that occur on campuses happen in either the victim's dorm or apartment.[49] These rapes occur more often off campus than on campus.[49]

A 2007 National Institute of Justice study found that, in terms of perpetrators, about 80% of survivors of physically forced or incapacitated sexual assault were assaulted by someone that they knew.[50]

The 2015 AAU Campus Climate Survey report found that transgender and gender non-conforming students were more likely than their peers to experience a sexual assault involving physical force or incapacitation. Out of 1,398 students who identified as TGQN, 24.1% of undergraduates and 15.5% of graduate/professional students reported experiencing a sexual assault involving physical force since enrolled. By comparison, 23.1% of female undergraduates and 8.8% of female graduate students reported the same type of sexual assault, along with 5.4% of male undergraduates and 2.2% of male graduate/professional students. Overall, sexual assault or misconduct was experienced at a rate of 19% among transgender and gender non-conforming students, 17% among female students, and 4.4% of male students.[51][52]

Many victims completely or partially blame themselves for the assault because they are embarrassed and shamed, or fear not being believed[53]. These elements may lead to underreporting of the crime. According to research, "myths, stereotypes, and unfounded beliefs about male sexuality, in particular male homosexuality", contribute to underreporting among males. In addition, "male sexual assault victims have fewer resources and greater stigma than do female sexual assault victims."[54] Hispanic and Asian students may have lower rates of knowing a victim or perpetrator due to cultural values discouraging disclosure.[55]

The Neumann study found that fraternity members are more likely than other college students to engage in rape; surveying the literature, it described numerous reasons for this, including peer acceptance, alcohol use, the acceptance of rape myths, and viewing women as sexualized objects, as well as the highly masculinized environment.[56] Although gang rape on college campuses is an issue, acquaintance, and party rape (a form of acquaintance rape where intoxicated people are targeted) are more likely to happen.[57]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

[edit]10% of sexual minority men, 18% of sexual minority women, and 19% of non-binary or transitioning students reported an unwanted sexual encounter since beginning college as opposed to the heterosexual majority.[58]

A direct association has been found between internalized homophobia and unwanted sexual experiences among LGBTQ college-aged students, suggesting that the specific stresses of identifying as LGBTQ as a college-aged student puts people more at risk for sexual violence.[59] The obstacles that LGBTQ students face with regard to sexual assault can be attributed not only to internalized homophobia, but also to institutionalized heterosexism and cisexism within college campuses.[60]

Disclosure rates

[edit]Within the broader category of LGBTQ students as a whole, gendered and racial trends of sexual violence mirror those of sexual violence among heterosexual college students, with sexual violence occurring at a higher rate among women and Black/African-American young adults. When LGBTQ disclose to a formal resource like a doctor or counselor they are often ill-equipped to deal with the specific vulnerabilities and stresses of LGBTQ students, leading LGBTQ students to be less likely to disclose in the future.[61]

Sexual violence and mental health

[edit]There is research that indicates that there is an association between sexual violence and a mental-health problems.[62] These problems vary from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), depression, psychosis, and substance abuse problems. The research also indicates that a high percentage of people that use mental-health resources for help have had experience with sexual violence.[62]

Incidents of sexual assault among LGBTQ students may be influenced by a variety of situational factors. Many members of the LGBTQ youth community suffer from serious depression and suicidal thoughts. The prevalence of attempted suicide among LGBTQ populations ranges from 23% to 42% for youth.[63] Many LGBTQ youth use alcohol to cope with depression. One study found that 28% of those [who are "those"?] interviewed had received treatment for alcohol or drug abuse.[63] Furthermore, rates of substance use and abuse are much higher among LGBTQ college students than heterosexuals, with LGBTQ women being 10.7 times more likely to drink than heterosexual women.[64] Unfortunately, many predators target those appearing to be vulnerable and it was found that over one half of all sexual abuse victims reported they had been drinking when they were abused.[65]

Risk factors

[edit]Researchers have identified a variety of factors that contribute to heightened levels of sexual assault on college campuses. Individual factors (such as alcohol consumption, impersonal sexual behavior and hostile attitudes toward women), environmental and cultural factors (such as peer group support for sexual aggression, gender role stress and skewed gender ratios), as well inadequate enforcement efforts by campus police and administrators have been offered as potential causes. In addition, general cultural notions relating to victim-blaming are at play as the majority of assaults are never reported due to shame or fear.[30]

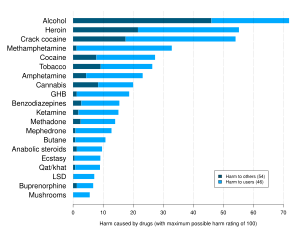

Influence of alcohol

[edit]

Both victims and perpetrators of sexual assault frequently report that they were consuming alcohol when the assault occurred. For instance, the 2007 Campus Sexual Assault study found that most sexual assaults occurred after women voluntarily consumed alcohol.[3] In a 1998 study, 47% of men who admitted to having committed a sexual assault also reported that they were drinking alcohol at the time of the attack.[67]

During social interactions, alcohol consumption encourages biased appraisal of a partner's sexual motives, impairs communication about sexual intentions, and enhances misperception of sexual intent. These effects are exacerbated by peer influence about how to act when drinking.[68] The effects of alcohol at point of forced sex are likely to impair ability to rectify misperceptions, diminish ability to resist sexual advancements, and justifies aggressive behavior.[68] Alcohol provides justification for engaging in behaviors that are usually considered inappropriate. The increase of assaults on college campuses can be attributed to the social expectation that students participate in alcohol consumption. The peer norms on American college campuses are to drink heavily, to act in an uninhibited manner and to engage in casual sex.[69] However, a study on the reports of women in college shows that their substance use is not a risk factor for forced sexual assault, but is a risk factor for sexual assault while the victim is incapacitated.[46]

Various studies have concluded the following results:

- At least 47% of college students' sexual assaults are associated with alcohol use[21]

- Women whose partners abuse alcohol are 3.6 times more likely than other women to be assaulted by their partners[70]

- In 2013, more than 14,700 students between the ages of 18 and 24 were victims of alcohol-related sexual assault in the U.S.[21]

- In those violent incidents recorded by the police in which alcohol was a factor, about 9% of the offenders and nearly 14% of the victims were under age 21[71]

Some have noted gender-specific and variable standards for intoxicated consent. In a recent lawsuit against Duke University, a Duke administrator, when asked whether verbal consent need be mutual when both participants are drunk, stated, "Assuming it is a male and female, it is the responsibility in the case of the male to gain consent before proceeding with sex."[72][73][74] Other institutions state only that a rape victim has to be "intoxicated" rather than "incapacitated" by alcohol or drugs to render consent impossible.[75][76][77][78]

In one study[44] that Antonia Abby describes in her article, a group of 160 men students listen to an audiotape recording of a date rape. In the beginning the woman agrees to kissing and touching but once the man tries to remove her clothes and she refuses the male becomes more aggressive verbally and physically. The men were asked to stop the tape at the point that they felt the man's behavior was inappropriate. "Participants who consumed alcohol allowed the man to continue for a longer period of time and rated the women's sexual arousal higher than did sober participants. The findings suggest that intoxicated men may project their own sexual arousal onto a women, missing or ignoring her active protest".[44]

A study conducted by Elizabeth Armstrong, Laura Hamilton and Brian Sweeney in 2006 suggests that it is the culture and gendered nature of fraternity parties that create an environment with greater likelihood of sexual assault. They state "Culture expectations that party goers drink heavily and trust party-mates become problematic when combined with expectations that women be nice and defer to men. Fulfilling the role of the parties produced vulnerability on the part of women, which some men exploit to extract non-consensual sex".[30]

Alcohol is a factor in many rapes and other sexual assaults. As the study by Armstrong, Hamilton, and Sweeney suggests it might be one of the reasons for the under-reporting of rape where because of having been drinking victims fear that they will be ignored or not believed.[30]

Attitudes

[edit]Individual and peer group attitudes have also been identified as an important risk factor for the perpetration of sexual assault among college aged men in the United States. Both the self-reported proclivity to commit rape in a hypothetical scenario, as well as self-reported history of sexual aggression, positively correlate with the endorsement of rape tolerant or rape supportive attitudes in men.[79][80] Acceptance of rape myths – prejudicial and stereotyped beliefs about rape and situations surrounding rape such as the belief that "only promiscuous women get raped" or that "women ask for it" – are correlated with self reported past sexual aggression and with self-reported willingness to commit rape in the future among men.[81]

A 2007 study found that college-aged men who reported previous sexual aggression held negative attitudes toward women and gender roles, were more acceptant of using alcohol to obtain sex, were more likely to believe that rape was justified in some circumstances, were more likely to blame women for their victimization, and were more likely to view sexual conquest as an important status symbol.[82][83]

According to sociologist Michael Kimmel, rape-prone campus environments exist throughout several university and college campuses in North America. Kimmel defines these environments as "one in which the incidence of rape is reported by observers to be high, or rape is excused as a ceremonial expression of masculinity, or rape as an act by which men are allowed to punish or threaten women."[84]

The Red Zone

[edit]The Red Zone refers to spikes in sexual assault incidents that occur on college campuses in the fall semester (typically August through November). The red zone disproportionately impacts first-year female students who are still getting acclimated to a new college environment.[85] Being away from guardians and friends, as well as (in some cases) living in a new city leaves freshmen vulnerable to substance use and other students. Additionally, those who participate in ‘rushing’ (the process of joining a sorority or fraternity) are more likely to be exposed to alcohol and party culture[85]

History of the Red Zone

[edit]The term ‘red zone’ first appeared in freelance journalist Robin Warshaw’s book I Never Called It Rape, which was published in 1998.[86] Warshaw discusses survey data collected from college campuses across the nation and the frequency of acquaintance rape, as opposed to rape perpetrated by a person unknown to the victim,[87] on these campuses. Multiple sources[88][89] claim that David Lisak, a clinical psychologist and former associate professor from the University of Massachusetts Boston[90] coined the term ‘red zone’. Lisak is known for his work and research on sexual violence perpetrated by men. However, red zones have not been mentioned in any of Lisak’s publications.

Statistics on the Red Zone

[edit]Freshmen may be more vulnerable to sexual assault during their first semester because they do not have close friends who could intervene if they are in danger of assault, or because they are not aware of informal strategies that older students use to avoid unwanted sexual attention. [91]A 2008 study by Kimble et al. [92] also found support for the claim that sexual assaults happened more frequently in the fall semester, but the authors cautioned that "local factors" such as the timing of semesters, the campus residential system, or the timing of major fraternity events may influence the temporal risk of sexual assault.

More than 50% of all sexual assault cases occur during the period of move-in to the last day before Thanksgiving (August-November) as people are unfamiliar with the campus and may be trying out drugs or alcohol for the first time. Most campus sexual assaults are perpetrated by someone the victim knows.[93] While stranger assault occurs the majority of sexual assaults are perpetrated by acquaintance. Freshman who are female, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ are often most targeted during the red zone.[94] Also, those who have experienced sexual assault in the first semester of college often have higher rates of anxiety and depression.[95]

Furthermore, many researchers point out the risk of Greek life and frat parties to getting drugged, as they often provide opportunities for unmonitored alcohol consumption. In 2022, Cornell University, which has the third largest Greek life system in the nation, suspended all parties and social events linked to Greek life following an increase in reported incidents of drugging at parties[96]

Prevention efforts

[edit]In the United States, Title IX prohibits gender-based discrimination at any school or university that receives federal funding.[97] Since the 1980s, regulators and courts have held that preventing gender discrimination requires schools to implement policies to protect students from sexual violence or hostile educational environments, reasoning that these can limit women's ability to access to education. Under Title IX, schools are required to make efforts to prevent sexual violence and harassment, and to have policies in place for investigating complaints and protecting victims.[98] While schools are required to notify victims of sexual assault that they have a right to report their attack to the police, this reporting is voluntary. Schools are required to investigate claims and hold disciplinary procedures independently, regardless of whether a sexual assault is reported or investigated by police.[8] An estimated 83% of officers on college campuses are male, however, research shows that more female law enforcement officers increases the number of sexual assault reports.[99]

The best known articulation that rape and sexual assault is a broader problem was the 1975 book Against Our Will. The book broadened the perception of rape from a crime by strangers, to one that more often included friends and acquaintances, and raised awareness. As early as the 1980s, campus rape was considered an under-reported crime. Reasons included to the involvement of alcohol, reluctance of students to report the crime, and universities not addressing the issue.[100]

A pivotal change in how universities handle reporting stemmed from the 1986 rape and murder of Jeanne Clery in her campus dormitory. Her parents pushed for campus safety and reporting legislation which became the foundation for The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act. The Clery Act requires that all schools in the U.S. that participate in federal student aid programs implement policies for addressing sexual assault.[101][102]

A 2000 study by the National Institute of Justice found that only about a third of U.S. schools fully complied with federal regulations for recording and reporting instances of sexual assault, and only half offered an option for anonymous reporting of sexual assault victimization.[103] One recent study indicated that universities also greatly under-report assaults as part of the Clery Act except when they are under scrutiny. When under investigation, the reported rate by institutions rises 44%, only to drop back to baseline levels afterwards.[104]

Numerous colleges in the United States have come under federal investigation for their handling of sexual assault cases, described by civil rights groups as discriminatory and inappropriate.[105][106]

Mandatory reporting of campus sexual assaults has recently been included in proposed bills. In March 2015, the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence (NAESV) conducted a survey in conjunction with Know Your IX regarding the right of the survivor to choose to report the assault to police authorities versus legislation which would enforce legal action upon reporting sexual assault to a university or college. "When asked their concerns if reporting to police were mandatory, 79% said, "this could have a chilling effect on reporting", while 72% were concerned that "survivors would be forced to participate in the criminal justice system/go to trial".[107]

About 50% of sexual assaults that happen on campus typically happen between the beginning of the fall semester to Thanksgiving break. This is usually called the "red zone".[108] This time frame is said to be more dangerous for freshman students. Bustle explains, "These months are often full of booze-filled back-to-school parties, where freshman with little drinking experience (and few friends watching out for them) are especially vulnerable to attack."[108] It is very likely that freshman students are not as informed when it comes to taking preventative measures to avoid such attacks. Some tips would be to be aware of surroundings, pay attention to your drinks, and pay attention to your friends and make sure they are safe.

Affirmative consent policies

[edit]In an effort to police student conduct, some states such as New York, Connecticut, and California established that many schools require "affirmative consent" (commonly known as "yes means yes"). The policies require students to receive ongoing and active consent throughout any sexual encounter. The policies hold that "Silence or lack of resistance, in and of itself, does not demonstrate consent", in a shift away from "no means no" to a "yes means yes" requirement for sex to be consensual. Schools can include drug or alcohol intoxication in their considerations of whether a student granted consent under this policy such that a "drunk" student cannot give consent. These policies are challenging to students because non-verbal cues are difficult to interpret and the policies are confusing.[109] Furthermore, researchers have found that legal definitions of affirmative consent are not aligned with student understanding and practices.[110] There has also been push-back from the legal community. In May 2016, American Law Institute overwhelmingly rejected a proposal to endorse affirmative consent which would have otherwise required it to be included in the penal codes. A letter written to the committee by 120 members stated "By forcing the accused to prove the near-impossible – that a sexual encounter was vocally agreed upon at each stage – affirmative consent standards deny the accused due process rights."[111] A Tennessee court also found that student expelled under an affirmative consent policy was required to prove his innocence, contrary to legal practice and due process rights.

According to California's Yes Means Yes policy, California higher education institutes are required to enact specific protocols and policies in an attempt to combat power-based violence such as sexual assault on college campuses within the state. The state bill, as with others of the same degree, established the standard of consent known as "affirmative consent". This standard of consent placed the responsibility of attaining and maintaining consent to everyone involved in the sexual acts. In order to receive state funding for such matters, California campuses are responsible for collaborating with organizations both on and off campus in order to provide resources and assistance to the student body and make such services available when necessary. They must also exhibit prevention and outreach services to the campus community through programming, awareness campaigns, and education. This also includes holding awareness programming such as bystander intervention for incoming students during their orientation.[112]

Student and organizational activism

[edit]In response to the widespread issue of sexual violence on college campuses and inadequate measures taken by administration to protect survivors, students and other activist groups are organizing to challenge cultures of disbelief, victim blaming, and institutional neglect. These movements aim to advocate for systemic reforms that hold perpetrators accountable for criminal actions, provide sufficient counseling and support services, and afford students a safer campus environment. The first “Take Back the Night” march took place in 1978, in San Francisco, to protest violence against women. Since then, it has spread to college campuses across the nation.[113] The SlutWalk movement emerged in 2011 to combat rape culture and the slut-shaming of sexual assault victims.[114]

Some survivors of sexual violence have become notable activists. Emma Sulkowicz, then a student at Columbia University, created the performance art Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight). Lena Sclove, a student at Brown University, received media attention when she expressed that the one-year suspension of Daniel Kopin, who was accused of sexually assaulting her, was not an sufficient punishment due to the severity of the act he committed.[115] While Kopin has publicly disputed the report and was found not guilty by the criminal justice system, he was determined responsible under the university’s preponderance of the evidence standard. Such cases have led to controversy and concerns regarding presumption of innocence and due process, and have also highlighted the difficulties that universities face in balancing the rights of the accuser and the rights of the accused when dealing with cases of sexual assault.[116][117][118] Nearly 100 colleges and universities had a significant number of reports of rape on their main campuses in 2014, with Brown University and the University of Connecticut tied for the highest annual total — 43 each.[119] The Sulkowicz and Sclove cases have led to further complaints of bias by the men against the universities (Title IX or civil) regarding how they handled the matters.[120][121]

Chanel Miller, a student at UC Santa Barbara, was sexually assaulted by a Stanford student, Brock Turner, after attending a fraternity party at Stanford. Turner was charged with five counts of sexual assault but was sentenced to only six months in prison. Throughout the trial, Miller remained anonymous through the pseudonym "Emily Doe" but stirred the public with her victim impact statement, starting a nationwide conversation. She later identified herself and published a memoir titled Know My Name, which began her activism about rape on college campuses.

One outside group, UltraViolet, has used online media tactics, including search engine advertisements, to pressure universities to be more aggressive when dealing with reports of rape. Their social media campaign uses advertisements that sometimes lead with "Which College Has The Worst Rape Problem?" and other provocative titles that appear in online search results for a targeted school's name.[122]

Our Turn, a Canadian student-driven initiative to end campus sexual violence, began in 2017. The initiative was launched by three Carleton University students, including Jade Cooligan Pang, and soon spread to 20 student unions in eight Canadian provinces. In October 2017, Our Turn released a survey evaluating the sexual assault policies of 14 Canadian universities along with an action plan for student unions to support survivors of sexual assault.[123][124] The action plan includes creating Our Turn committees on campus to address sexual violence through prevention, support, and advocacy work at the campus, provincial, and national levels.[125]

In 2019, students at Princeton University staged a sit-in and social media campaign concerning the implementation of Title IX policies regarding sexual assault cases on Princeton's campus, which made national headlines.[126][127][128] The protests were conducted in response to a student's disciplinary sentence, which was considered retaliatory by protesters.[129]

The organization Students Against Institutional Violence at the University of Vermont is devoted to creating a safe and healthy environment for all students. The organization aims to combat various forms of discrimination, including sexual violence, racism, homophobia, transphobia, and ableism, through public education and advocacy. One of their primary initiatives is addressing the role Greek life plays in perpetuating rape culture. The group argues that the established policies and practices within fraternities act as an incubator for sexual violence and misconduct. They are calling on the university to commit to greater transparency and accountability, by rebuilding the Title IX website, simplifying the complex legal language used in the Title IX reporting process, and establishing an alternative pathway for reporting incidents beyond the traditional legal framework that is rooted in the values of restorative justice.[130]

In 2022, Students Against Institutional Violence took activism beyond campus, in providing testimony to the Vermont legislature in support of Bill H.40,[131] which would criminalize the non-consensual removal or tampering with a sexually protective device during intercourse, a practice known as “stealthing.” The student organization believes that the act of “stealthing” is sexual assault, as it involves consensual sex under false pretenses. Their advocacy marked a significant step in student involvement for legal protection against forms of sexual violence.[130]

In 2022, hundreds of students at the University of Vermont staged a protest in response to an Instagram post by the university, which simultaneously congratulated athletes and denounced anonymous accusations of sexual assault on social media. The demonstration, which coincided with Admitted Students Visit Day, moved through campus, including the Davis Center and Brennan’s Pub and Bistro, areas set aside for prospective students. UVM athletics faced intense backlash for protecting abusers within its institution, according to student sources, and the men’s basketball team in particular is the target for numerous allegations. One of the victims, graduate student Kendall Ware, spoke out about the mishandling of her sexual assault case during her time as an undergraduate.[132][133] She accused Anthony Lamb, now an NBA player, of assaulting her at an off-campus party in 2019, when he was a member of the men’s basketball team.[134]

Obama administration efforts

[edit]In 2011, the United States Department of Education sent a letter, known as the "Dear Colleague" letter, to the presidents of all colleges and universities in the United States re-iterating that Title IX requires schools to investigate and adjudicate cases of sexual assault on campus.[8] The letter also states that schools must adjudicate these cases using a "preponderance of the evidence" standard, meaning that the accused will be responsible if it is determined that there is at least a 50.1% chance that the assault occurred. The letter expressly forbade the use of the stricter "clear and convincing evidence" standard used at some schools previously. In 2014, a survey of college and university assault policies conducted at the request of the U.S. Senate found that more than 40% of schools studied had not conducted a single rape or sexual assault investigation in the past five years, and more than 20% had failed to conduct investigations into assaults they had reported to the Department of Education.[135] The "Dear Colleague" letter is credited by victim's advocates with de-stigmatizing sexual assault and encouraging victims to report. However it also created a climate where the accused rights are considered secondary. Brett Sokolow, executive director of the Association of Title IX Administrators and president of the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management stated, "I think probably a lot of colleges translated the 'Dear Colleague' letter as 'favor the victim'."[136]

In 2014, President Barack Obama established the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, which published a report reiterating the interpretation of Title IX in the "Dear Colleague" letter and proposing a number of other measures to prevent and respond to sexual assault on campus, such as campus climate surveys and bystander intervention programs.[137][138] One example of a campus climate survey that was developed in response to this task force is the ARC3 Survey. Shortly thereafter, the Department of Education released a list of 55 colleges and universities across the country that it was investigating for possible Title IX violations in relation to sexual assault.[139] As of early 2015, 94 different colleges and universities were under ongoing investigations by the U.S. Department of Education for their handling of rape and sexual assault allegations.[140]

In September 2014, President Obama and Vice President Joe Biden launched the "It's on Us" campaign as part of an initiative to end sexual assault on college campuses. The campaign partnered with many organizations and college campuses to get students to take a pledge to end sexual assault on campuses.[141][142]

Criticism

[edit]The Department of Education's approach toward adjudicating sexual assault accusations has been criticized for failing to consider the possibility of false accusations, mistaken identity, or errors by investigators. Critics claim that the "preponderance of the evidence" standard required by Title IX is not an appropriate basis for determining guilt or innocence, and can lead to students being wrongfully expelled. Campus hearings have also been criticized for failing to provide many of the due process protections that the United States Constitution guarantees in criminal trials, such as the right to be represented by an attorney and the right to cross-examine witnesses.[143]

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) has been critical of university definitions of consent that it considers overly broad. In 2011, FIRE criticized Stanford University after it held a male student responsible for a sexual assault for an incident where both parties had been drinking. FIRE said that Stanford's definition of consent, quoted as follows "A person is legally incapable of giving consent if under age 18 years; if intoxicated by drugs and/or alcohol;", was so broad that sexual contact at any level of intoxication could be considered non-consensual.[144][145][146] Writing for The Atlantic magazine, Conor Friedersdorf noted that a Stanford male who alleges he was sexually assaulted in 2015 and was advised against reporting it by on-campus sexual assault services, could have been subjected to a counterclaim based on Stanford policy by his female attacker who was drunk at the time.[147] FIRE was also critical of a poster at Coastal Carolina University, which stated that sex is only consensual if both parties are completely sober and if consent is not only present, but also enthusiastic. The FIRE argued that this standard converted ordinary lawful sexual encounters into sexual assault even while drinking is very common at most institutions.[148][149]

In May 2014, the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management, a law firm that advises colleges on liability issues, issued an open letter to all parties involved in the issue of rape on campus.[150] In it, NCHERM expressed praise for Obama's initiatives to end sexual assault on college campuses, and called attention to several areas of concern they hoped to help address. While acknowledging appreciation for the complexities involved in changing campus culture, the letter offered direct advice to each party involved in campus hearings, outlining the improvements NCHERM considers necessary to continue the progress achieved since the issuance of the "Dear Colleague" letter in 2011. In early 2014, the group RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) wrote an open letter to the White House calling for campus hearings to be de-emphasized due to their lack of accountability for survivors and victims of sexual violence. According to RAINN, "The crime of rape does not fit the capabilities of such boards. They often offer the worst of both worlds: they lack protections for the accused while often tormenting victims."[151]

Many institutions today are facing Title IX investigations due to the alleged lack of response on their campus to sexual assault. New policies by colleges have spawned "a cottage industry" of experts to address sexual assault on their campuses. "The Federal Education Department urges colleges to make sure their discipline policies do not discourage students from coming forward to report sexual assaults."[152] Colleges need to be away of their policies in order to not victim blame their students and provide them with the adequate support that is need for the student. Many campuses are facing the same challenges on how to address the problem of sexual assault and are taking measures to do so, by hiring teams for addressing Title IX complaints.[153]

In October 2014, 28 members of the Harvard Law School Faculty co-signed a letter decrying the change in the way reports of sexual harassment are being processed.[9] The letter asserted that the new rules violate the due process rights of the responding parties. In February 2015, 16 members of the University of Pennsylvania Law School Faculty co-signed a similar letter of their own.[154]

In response to concerns, in 2014 the White House Task Force provided new regulations requiring schools to permit the accused to bring advisers and be clearer about their processes and how they determine punishments. In addition to concerns about legal due process, which colleges currently do not have to abide, the push for stronger punishments and permanent disciplinary records on transcripts can prevent students found responsible from ever completing college or seeking graduate studies. Even for minor sexual misconduct offenses, the inconsistent and sometimes "murky" notes on transcripts can severely limit options. Mary Koss, a University of Arizona professor, co-authored a peer-reviewed paper in 2014 that argues for a "restorative justice" response – which could include counseling, close monitoring, and community service – as a better paradigm than the judicial model most campus hearing panels resemble.[155]

Some critics of these policies have characterized the concerns about sexual assault on college campuses as a moral panic, such as libertarian critics of feminism Cathy Young,[156] Laura Kipnis,[157] and Christina Hoff Sommers who criticized the CDC 1 in 5 statistic by claiming issues with its methodology and that it did not line up with the Bureau of Justice Statistics pointing to "approximately one-in-forty college women".[158]

Lawsuits

[edit]Since the issuance of the "Dear Colleague" letter, a number of lawsuits have been filed against colleges and universities by male students alleging that their universities violated their rights over the course of adjudicating sexual assault accusations.[10] Xavier University entered into a settlement in one such lawsuit in April 2014.[159]

Other examples include:

- In October 2014, a male Occidental College student filed a Title IX complaint against the school after he was expelled for an alleged sexual assault. The assault occurred after a night of heavy drinking in which both parties were reported to have been extremely impaired. The investigator hired by the school found that although the accuser had sent multiple text messages indicating an intent to have sex, found and entered the accused student's bedroom under her own power, and told witnesses she was fine when they checked on her during the sex acts, her estimated level of intoxication meant she was incapacitated and did not consent. A police investigation however found that "witnesses were interviewed and agreed that the victim and suspect were both drunk [and] that they were both willing participants exercising bad judgement."[160][161] The accused student attempted to file a sexual assault claim against his accuser, but the university declined to hear his complaint because he would not meet with an investigator without an attorney present.[162]

- In March 2015, federal regulators (OCR) opened an investigation on how Brandeis University handles sexual assault cases, stemming from a lawsuit where a male student was found responsible for sexual misconduct. The accused was not permitted to see the report created by the special investigator that determined his responsibility until after a decision had been reached.[163][164]

- In June 2015 an Amherst College student who was expelled for forcing a woman to complete an oral sex act sued the college for failing to discover text messages from the accuser that suggested consent and undermined her credibility. The accuser said she described the encounter as consensual because she was not "yet ready to address what had happened". The suit alleges that the investigation was "grossly inadequate". When student later learned of the messages favorable to him, Amherst refused to reconsider the case.[165] In its response to the lawsuit, the school stated the process was fair and that the student had missed the seven-day window in which to file an appeal.[166]

- In July 2015 a California court ruled that the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) acted improperly by using a deeply flawed system to adjudicate a sexual assault allegation and sanctioning the accused based on a process that violated his rights. The student was not given adequate opportunity to challenge the accusations and the panel relied on information deliberately withheld from the student despite repeated requests. The judge also admonished a dean who had punitively increased the student's penalty without explanation each time he appealed, while the student's counsel criticized the dean for a perceived conflict of interest.[167]

- In August 2015, a Tennessee judge ruled against the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga who expelled a student for rape under a "yes-means-yes" policy. The student had been cleared by the school which later reversed its opinion on appeal using an affirmative consent policy. The judge found the school had no evidence the accuser did not consent, and found the school had "improperly shifted the burden of proof and imposed an untenable standard upon" the student "to disprove the accusation" that he assaulted a classmate.[168][169]

- In June 2017, a divided panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found that the University of Houston did not violate the Constitution's Due Process Clause or Title IX when it expelled a student for committing sexual assault in a dorm room then abandoning the nude victim in a dorm elevator, as well as his girlfriend, who had recorded the assault and shared the video on social media.[170][171]

- A former Boston College student has won more than $100,000 from his alma mater after a federal jury found the private nonprofit institution mishandled sexual assault allegations against him. The case is significant in that it is the first sex assault lawsuit against a university to reach a jury trial since 2011, when the Obama administration rewrote the rules for how college officials should investigate and arbitrate sexual violence on campuses.[172]

- In February 2022, The University of California agreed to pay almost $250m to over 200 women who were allegedly sexually assaulted by a campus gynecologist.[173]

Trump administration efforts

[edit]On 22 September 2017, Betsy DeVos, the Secretary of Education in the Trump administration, rescinded some Obama-era campus guidelines regarding campus sexual assault. The rescinded guidelines included: having a low standard of proof to establish guilt, a 60-day investigation period, and not permitting mediation between involved parties.[174]

In May 2020, DeVos released the finalized new set of regulations under Title IX. Some of the new regulations hold that employees, such as faculty, athletic staff, and more, are no longer required to report allegation of sexual misconduct and those going through misconduct investigations are required to hold live hearings with the opportunity to cross-examine the accuser. If an assault happens outside of campus grounds, they no longer fall under Title IX protections. This is regardless to the fact if any or all parties involved are students. Allegations must meet the new criteria in order to formally be investigated, otherwise schools are allowed to dismiss the case. Kathryn Nash, a higher education attorney at Lathrop GPM states, "under the new regulations, to meet the definition of sexual harassment, the conduct 'has to be so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the recipient's education program or activity, so that's definitely a higher burden.'"[175]

Criticisms/General Response

[edit]University of California system response

[edit]After the announcement of the new finalized Title IX regulations, the UC system president, Janet Napolitano, released a statement in response. In this statement, Napolitano announced their opposition with these new rules. It is believed by the UC system that along with the challenges faced by COVID-19, these new regulations will only further the barrier already in place when it comes to reporting. Their largest concern comes from the direct-examination students will be subject to if a formal complaint turns into an investigation. Lower standards from schools is also seen to "weaken fair and just policies that have taken decades to establish." However, there were aspects that the system agreed with, such as the inclusion relationship violence into the mix.[176]

College programs

[edit]Some colleges and universities have taken additional steps to prevent sexual violence on campus. These include educational programs designed to inform students about risk factors and prevention strategies to avoid victimization, bystander education programs (which encourage students to identify and defuse situations that may lead to sexual assault), and social media campaigns to raise awareness about sexual assault.[103] FYCARE is one example of an educational program designed to inform students that the University of Illinois has implemented. FYCARE is a new student program that each student at the university is required to take. It focuses on informing students of sexual assault on campus and how they too can get involved in the fight against sexual assault.[177] A cheerful banner campaign at a large university found positive results, suggesting that an upbeat campaign can engage students in productive conversation.[178]

The Bystander Intervention programs is a system many schools are promoting to help students to feel empowered and knowledgeable. The program provides skills to effectively assist in the prevention of sexual violence. This gives a specific to that students can use in preventing sexual violence, including naming and stopping situations that could lead to sexual violence before it happens, stepping in during an incident, and speaking out against ideas and behaviors that support sexual violence. A few schools that are currently promoting the program are Johnson County Community College,[179] The University of Massachusetts,[180] Massachusetts Institute of Technology,[181] and Loyola University of Chicago.[182]

One study found that a large percentage of university students know victims of sexual assault, and that this personal knowledge differs among ethnic groups. These findings have implications for college programs, suggesting that prevention efforts be tailored to the group for which the program is intended.[183]

Media and Activism

[edit]Media shapes the perceptions and attitudes students have regarding sexual assault.

Since media has been around, students have found ways to incorporate it into their fight against sexual assault within colleges, universities, and institutions. Social media is an important tool on college campuses that pushes the conversation further, addresses myths, and helps provide education and support for survivors and allies. It is also a tool used for activism, in this case, student activism. Student activism is an organization or movement to push for systematic change on campus.

Before social media, activism was more biased and failed to address the implicit biases of race, gender, and class. Online activism and media have shown a new way to ensure inclusivity to those who are a part of marginalized groups. Media has done this by providing an open platform for students and a space for people to share stories which helps victims and survivors to feel less isolated and heal from their experiences. Social media also helps student activists connect with other student activists on other campuses, which builds a community and continues the progression of combating sexual assault in colleges.

Mainstream media is seen to primarily portray stereotypes of white women. Social media combats this by allowing activists to have a space to address the intersectionality within sexual assault in ways the mainstream media does not. Media also provides rape myths, false accusations and does not always provide all the facts of a case. This can cause a culture where victims on a college campus are hesitant to report a sexual assault.

Effective media campaigns to enhance student awareness can not be created without understanding the relationship students have with media and the mindset students have regarding sexual assault. Repetitive exposure to sexual assault in the media will help students understand the topic's importance. Incorporating campaigns to correct students' misconceptions about sexual assault can help reduce myths and stereotypes.

The hashtag and sharing function on social media platforms helps to reach audiences and demographics that may not have seen it otherwise. Younger generations, such as college students, use social media as their primary source to gain information. Hashtags are significant when it comes to sexual assault awareness within college campuses as they create easy access to a community of support for survivors, victims, and activists. Survivors can share their stories which could then have the potential to impact and help new and old victims who are working to heal. The #MeToo is a pivotal point in media involvement and an example of how Hashtags have been used.[184]

International students

[edit]As the development of the educational system around the world, more and more students have the opportunity to study abroad and gain knowledge and experiences. International students can be a victim of domestic violence, sexual harassments, psychological abuse and physical assaults. Women international students often find themselves in a uncomfortable situation where these assaults take place and may not be able how respond to these situations. Women international students may experience discomfort and possibly lack knowledge on how to react when the assaults occur.[185] Americans take advantage of women international students knowing that they may not fully understand or speak English.[186] Rates of sexual assault is common within domestic students rather than international students. It is less common for international students to become a victim rather than a domestic students. However, studies show that male international students are at greater risk of becoming a victim of sexual assaults than male domestic students.[187] For the students involved with the Asian community who are attending a university/college in the United States, studies show a 7% rate of sexual assault on campus.[188] Universities/Colleges in the United States understand the effects of campus sexual assaults and find ways to bring their percentage down.

Gap between cultures and the impact of sexual assaults

[edit]According to Pryor et al. (1997), the definition of sexual assault can differ depending on the countries and cultures and some students are unaware of what behaviors are considered to be sexual harassment in the country or culture where they are studying. Research conducted by Pryor et al. reported that college student definitions of sexual harassment in Germany, Australia, Brazil, and North America vary. They found that the most frequent definitional response for North Americans, Australians, and Germans includes unwanted verbal or physical sexual overtures. The most common response for Brazilian college students was "to seduce someone, to be more intimate (sexually), to procure a romance".[189] In addition, they found that Australians, Germans, and North Americans defined sexual harassment as an abuse of power, gender discrimination, and harmful sexual behavior. Brazilians defined sexual harassment as innocuous seductive behaviors. In this case, the certain student groups which have lower standards to the sexual assaults are easier to be assaulted.[189] When students are unable to confirm whether the type of assault will match the country and culture's definition of sexual assault, they are at risk of exhibiting behaviors such as a loss of morale, dissatisfaction with their career goals, or perform more poorly in school.[190][191]

Education

[edit]Levels of sexual education can differ depending on the country, which runs a risk of a lack of understanding of the domestic definitions of sexual assault and the legal repercussions. If a student is found to have committed sexual assault this can lead to their dismissal from the college or influence their visa status. Some campuses provide orientation programs to international students within a few days of their arrival, where the school laws and solutions for dangerous solutions are covered. These programs may not take into consideration if the student is familiar with the topics being discussed or potential language or cultural barriers.[192][193]

See also

[edit]- Bullying in academia

- Campus Accountability and Safety Act, pending

- Duke lacrosse case, notable for false rape accusation at Duke University

- The Hunting Ground (2015), documentary film about this issue

- Post-assault treatment of sexual assault victims

- Rape chant

- Rape in the United States#Jurisdiction

- "A Rape on Campus", a now-discredited and withdrawn article on an alleged gang rape at the University of Virginia

- Safe Campus Act

- Sexual harassment in education

- Violence against women

- Violence against men

- Campus Police

- Vanderbilt rape case

- Sexual Violence and Misconduct Policy Act (British Columbia)

References

[edit]- ^ "Sexual Assault US Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Statistics". National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Campus Sexual Assault Survey" (PDF). National Institute of Justice. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (21 September 2015). "Survey: More than 1 in 5 female undergrads at top schools suffer sexual attacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ "Report on the AAU Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct" (PDF). 21 September 2015: 82. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Krebs, Christopher P.; Lindquist, Christine H.; Warner, Tara D.; Fisher, Bonnie S.; Martin, Sandra L. (December 2007). "The Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) Study" (PDF). National Institute of Justice.

- ^ Deborah, Tuerkheimer (2017). "Incredible Women: Sexual Violence and the Credibility Discount". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 166 (1).

- ^ a b c "Dear Colleague Letter". United States Department of Education. 4 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Rethink Harvard's sexual harassment policy", The Boston Globe, 14 October 2014.

- ^ a b Schow, Ashe, "Backlash: College men challenge 'guilty until proven innocent' standard for sex assault cases", Washington Examiner, 11 August 2014 | Other Sources:

- Van Zuylen-Wood, Simon (11 February 2014). "Expelled Swarthmore Student Sues College Over Sexual Assault Allegations". Philadelphia.

- Parra, Esteban (17 December 2013). "DSU student who was cleared of rape charges sues school". The News Journal. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Muehlenhard, Charlene L.; Peterson, Zoe D.; Humphreys, Terry P.; Jozkowski, Kristen N. (16 May 2017). "Evaluating the One-in-Five Statistic: Women's Risk of Sexual Assault While in College". The Journal of Sex Research. 54 (4): 565. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1295014. PMID 28375675. S2CID 3853369.

As discussed, evidence does not support the assumption that college students experience more sexual assault than nonstudents

- ^ Muehlenhard, Charlene L.; Peterson, Zoe D.; Humphreys, Terry P.; Jozkowski, Kristen N. (16 May 2017). "Evaluating the One-in-Five Statistic: Women's Risk of Sexual Assault While in College". The Journal of Sex Research. 54 (4): 549–576. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1295014. PMID 28375675. S2CID 3853369.

- ^ DeKeseredy, Walter; Kelly, Katharine (1993). "The incidence and prevalence of woman abuse in Canadian university and college dating relationships". Canadian Journal of Sociology. 18 (2): 137–159. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.457.8310. doi:10.2307/3341255. JSTOR 3341255.

- ^ Gavey, Nicola (June 1991). "Sexual victimization prevalence among New Zealand university students". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 59 (3): 464–466. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.3.464. PMID 2071732.

- ^ NUS (2011). Hidden Marks: A study of women student's experiences of harassment, stalking, violence, and sexual assault (PDF) (2nd ed.). London, UK: National Union of Students. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Ellen R. Girden; Robert Kabacoff (2010). Evaluating Research Articles From Start to Finish. SAGE Publishing. pp. 84–92. ISBN 978-1-4129-7446-2.

- ^ Alexander, Linda Lewis; LaRosa, Judith H.; Bader, Helaine; Garfield, Susan; Alexander, William James (2010). New Dimensions in Women's Health (5th ed.). Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-7637-6592-7.

- ^ Fisher, Bonnie; Daigle, Leah E.; Cullen, Frank (2010), "Being pursued: the stalking of female students", in Fisher, Bonnie; Daigle, Leah E.; Cullen, Frank (eds.), Unsafe in the ivory tower: the sexual victimization of college women, Los Angeles: Sage Pub., pp. 149–170, ISBN 9781452210483.

- ^ "Understanding Sexual Assault on Campus | BestColleges". www.bestcolleges.com. 10 September 2021.

- ^ a b Rennison, C. M.; Addington, L. A. (2014). "Violence Against College Women: A Review to Identify Limitations in Defining the Problem and Inform Future Research". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 15 (3): 159–69. doi:10.1177/1524838014520724. ISSN 1524-8380. PMID 24488114. S2CID 29919847.

- ^ a b c Sinozich, Sofi; Langton, Lynn. "Rape and Sexual Assault Victimization Among College-Age Females, 1995–2013". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Kruttschnitt, Candace; Kalsbeek, William D.; House, Carol C. (2014). Estimating the Incidence of Rape and Sexual Assault. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN 9780309297370. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ a b Pugh, Brandie; Ningard, Holly; Ven, Thomas Vander; Butler, Leah (2016). "Victim Ambiguity: Bystander Intervention and Sexual Assault in the College Drinking Scene". Deviant Behavior. 37 (4): 401–418. doi:10.1080/01639625.2015.1026777. S2CID 147081204.

- ^ Pugh, Brandie; Becker, Patricia (2 August 2018). "Exploring Definitions and Prevalence of Verbal Sexual Coercion and Its Relationship to Consent to Unwanted Sex: Implications for Affirmative Consent Standards on College Campuses". Behavioral Sciences. 8 (8): 69. doi:10.3390/bs8080069. ISSN 2076-328X. PMC 6115968. PMID 30072605.

- ^ Douglas, K. A.; et al. (1997). "Results from the 1995 national college health risk behavior survey". Journal of American College Health. 46 (2): 55–66. doi:10.1080/07448489709595589. PMID 9276349.

- ^ "Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: The National College Health Risk Behavior Survey -- United States, 1995". Centers for Disease Control. 14 November 1997.

- ^ "RAINN | The nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization". www.rainn.org. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Title IX and Sexual Violence in Schools". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Taylor Jr, Stuart S. (23 September 2015). "The latest big sexual assault survey is (like others) more hype than science". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Armstrong, Elizabeth A.; Hamilton, Laura; Sweeney, Brian (December 1986). "Sexual assault on campus: a multilevel, integrative approach to party rape". Social Problems. 53 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.483. JSTOR 10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.483. S2CID 1439339. Pdf.

- ^ Forbes, Gordon B.; Adams-Curtis, Leah E. (September 2001). "Experiences with sexual coercion in college males and females: Role of family conflict, sexist attitudes, acceptance of rape myths, self-esteem, and the big-five personality factors". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 16 (9): 865–889. doi:10.1177/088626001016009002. S2CID 144942840.

- ^ Schwartz, Martin D.; Dekeseredy, Walter S.; Dekeseredy, Walter (1997). "Factors Associated with Male Peer Support for Sexual Assault on the College Campus". Sexual Assault on the College Campus: The Role of Male Peer Support. pp. 97–136. doi:10.4135/9781452232065.n4. ISBN 9780803970274.

- ^ Olfman, Sharna (2009). The Sexualization of Childhood. ABC-CLIO. p. 9.

- ^ Humphrey, Stephen E.; Kahn, Arnold S. (December 2000). "Fraternities, athletic teams, and rape importance of identification with a risky group". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 15 (12): 1313–1322. doi:10.1177/088626000015012005. S2CID 145183438.

- ^ Schwartz, Martin D.; Nogrady, Carol A. (June 1996). "Fraternity membership, rape myths, and sexual aggression on a college campus". Violence Against Women. 2 (2): 148–162. doi:10.1177/1077801296002002003. PMID 12295456. S2CID 13110688.

- ^ Lisak, David (March–April 2011). "Understanding the predatory nature of sexual violence" (PDF). Sexual Assault Report (SAR). 14 (4): 49–50, 55–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2015. Original pdf. Archived 18 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lauerman, Connie (15 September 2004). "Easy targets". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Lisak, David; Miller, Paul M. (February 2002). "Repeat rape and multiple offending among undetected rapists". Violence and Victims. 17 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.1.73.33638. PMID 11991158. S2CID 8401679. Pdf. Archived 30 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Swartout, Kevin M.; Koss, Mary P.; White, Jacquelyn W.; Thompson, Martie P.; Abbey, Antonia; Bellis, Alexandra L. (July 2015). "Trajectory analysis of the campus serial rapist assumption". JAMA Pediatrics. 169 (12): 1148–54. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0707. PMID 26168230.

- ^ Nicholson, Mary E.; Wang, Min Qi; Maney, Dolores; Yuan, Jianping; Mahoney, Beverly S.; Adame, Daniel D. (1998). "Alcohol related violence and unwanted sexual activity on the college campus". American Journal of Health Studies. 14 (1): 1–10. Pdf.

- Also available as: Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 8.

- ^ a b Bohmer, Carol; Parrot, Andrea (1993). Sexual assault on campus : the problem and the solution. Internet Archive. New York : Lexington Books ; Toronto : Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; New York : Maxwell Macmillan International. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-02-903715-7.

- ^ "Alanna Berger: The dark history of college football". The Michigan Daily. 27 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ Carone, Angela (2016), "Fraternities are significantly responsible for campus sexual assault", in Lasky, Jack (ed.), Sexual assault on campus, (Opposing Viewpoints Series), Farmington Hills, Michigan: Greenhaven Press, p. 21, ISBN 9780737775617.

- ^ a b c Abby, Antonia (2016), "What's alcohol got to do with it?", in Lasky, Jack (ed.), Sexual assault on campus, (Opposing Viewpoints Series), Farmington Hills, Michigan: Greenhaven Press, pp. 52–69, ISBN 9780737775617.

- ^ Carone, Angela (2016), "Fraternities are significantly responsible for campus sexual assault", in Lasky, Jack (ed.), Sexual assault on campus, (Opposing Viewpoints Series), Farmington Hills, Michigan: Greenhaven Press, pp. 21–23, ISBN 9780737775617.

- ^ a b Krebs, C.P. (2009). "The differential risk factors of physically forced and alcohol- or other drug-enabled sexual assault among university women". Violence and Victims. 24 (3): 302–321. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.3.302. PMID 19634358. S2CID 30026107. ProQuest 208558153.

- ^ Furtado, C., "Perceptions of Rape: Cultural, Gender, and Ethnic Differences" in Sex Crimes and Paraphilia Hickey, E.W. (ed.), Pearson Education, 2006, ISBN 0-13-170350-1, pp. 385–395.

- ^ Flowers, R.B., Sex Crimes, Perpetrators, Predators, Prostitutes, and Victims, 2nd Edition, p. 28.

- ^ a b Flowers, Barri (2009). "Sexual Assault". College Crime. McFarland. pp. 60–79.

- ^ "Rape on College Campus". Union College. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Munguia, Hayley (22 September 2015). "Transgender students are particularly vulnerable to campus sexual assault". fivethirtyeight.com. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ New, Jake. "The 'invisible' one in four". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Baum, Matthew A.; Cohen, Dara Kay; Zhukov, Yuri M. (2018). "Does Rape Culture Predict Rape? Evidence from U.S. Newspapers, 2000–2013". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 13 (3): 263–289. doi:10.1561/100.00016124. ISSN 1554-0626.

- ^ Bullock, Clayton M; Beckson, Mace (April 2011). "Male victims of sexual assault: phenomenology, psychology, physiology". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 39 (2): 197–205. PMID 21653264. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Sorenson, SB; Joshi, M; Sivitz, E (2014). "Knowing a sexual assault victim or perpetrator: A stratified random sample of undergraduates at one university". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 29 (3): 394–416. doi:10.1177/0886260513505206. PMID 24128425. S2CID 8130347.

- ^ Neumann, S., "Gang Rape: Examining Peer Support and Alcohol in Fraternities" in Sex Crimes and Paraphilia Hickey, E.W. (ed.), Pearson Education, 2006, ISBN 0-13-170350-1 pp. 397–407.

- ^ Thio, A., 2010. Deviant Behavior, 10th Edition

- ^ Murchison, Gabriel; et al. (2017). "Minority Stress and the Risk of Unwanted Sexual Experiences in LGBQ Undergraduates". Sex Roles. 77 (3/4): 221–238. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0710-2. S2CID 151525298.

- ^ Hughes, Tonda L.; et al. (2010). "Sexual Victimization and Hazardous Drinking among Heterosexual and Sexual Minority Women". Addictive Behaviors. 35 (12): 221–238. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004. PMC 3006188. PMID 20692771.

- ^ Juarez, Tamara (May 2017). "A Survivor's Strength". Echo Magazine. 28 (8): 52–53.

- ^ Reuter, Tyson R.; et al. (2017). "Intimate Partner Violence Victimization in LGBT Young Adults: Demographic Differences and Associations with Health Behaviors". Psychology of Violence. 7 (1): 101–109. doi:10.1037/vio0000031. PMC 5403162. PMID 28451465.

- ^ a b Oram, Sian (12 April 2019). "Sexual violence and mental health". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 28 (6): 592–593. doi:10.1017/S2045796019000106. ISSN 2045-7960. PMC 6998874. PMID 30977458.

- ^ a b Clements-Nolle, K.; Marx, R.; Katz, M. (2006). "Attempted Suicide Among Transgender Persons". Journal of Homosexuality. 51 (3): 53–69. doi:10.1300/J082v51n03_04. PMID 17135115. S2CID 23781746.

- ^ Ridner, S. L.; Frost, K.; LaJoie, A. S. (2006). "Health information and risk behaviors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual college students". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 18 (8): 374–378. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00142.x. PMID 16907699. S2CID 2336100.

- ^ Abbey, A., Ross, L. T., & McDuffie, D. (1995). Alcohol's role in sexual assault. In R. R. Watson (Ed.), Drug and alcohol abuse reviews, Vol. 5: Addictive behaviors in women (pp. 97–123). Totowa, NJ: Humana.