North Sentinel Island

North Sentinel Island in 2009 | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Bay of Bengal |

| Coordinates | 11°33′25″N 92°14′28″E / 11.557°N 92.241°E [1] |

| Archipelago | Andaman Islands[2] |

| Adjacent to | Bay of Bengal |

| Area | 59.67 km2 (23.04 sq mi)[3] |

| Length | 7.8 km (4.85 mi) |

| Width | 7.0 km (4.35 mi) |

| Coastline | 31.6 km (19.64 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 122 m (400 ft)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Union territory | The Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

| District | South Andaman |

| Tehsil | Port Blair[4] |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | North Sentinelese |

| Population | 39[5] (2018 estimate) actual population highly uncertain – may be as high as 400 |

| Population rank | Unknown |

| Ethnic groups | Sentinelese[2] |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| PIN | 744202[6] |

| ISO code | IN-AN-00[7] |

| Official website | andaman |

| Average summer temperature | 30.2 °C (86.4 °F) |

| Average winter temperature | 23 °C (73 °F) |

| Census Code | 35.639.0004 |

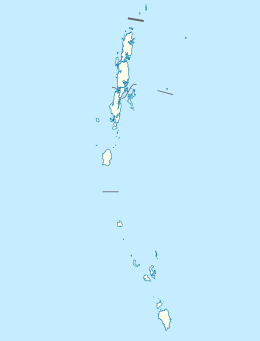

North Sentinel Island is one of the Andaman Islands, an Indian archipelago in the Bay of Bengal which also includes South Sentinel Island.[8] The island is a protected area of India. It is home to the Sentinelese, an indigenous tribe in voluntary isolation who have defended, often by force, their protected isolation from the outside world. The island is about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) long and 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) wide, and its area is approximately 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi).

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation 1956[9] prohibits travel to the island, and any approach closer than 5 nautical miles (9.3 km), in order to protect the remaining tribal community from "mainland" infectious diseases against which they likely have no acquired immunity. The area is patrolled by the Indian Navy.[10]

Nominally, the island belongs to the South Andaman administrative district, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[11] In practice, Indian authorities recognise the islanders' desire to be left alone, restricting outsiders to remote monitoring (by boat and sometimes air) from a reasonably safe distance; the Government of India will not prosecute the Sentinelese for killing people in the event that an outsider ventures ashore.[12][13] In 2018, the Government of India excluded 29 islands—including North Sentinel—from the Restricted Area Permit (RAP) regime, in a major effort to boost tourism.[14] In November 2018, the government's home ministry stated that the relaxation of the prohibition on visitations was intended to allow researchers and anthropologists (with pre-approved clearance) to finally visit the Sentinel islands.[15]

The Sentinelese have repeatedly attacked approaching vessels, whether the boats were intentionally visiting the island or simply ran aground on the surrounding coral reef. The islanders have been observed shooting arrows at boats, as well as at low-flying helicopters. Such attacks have resulted in injury and death. In 2006, islanders killed two fishermen whose boat had drifted ashore, and in 2018 an American Christian missionary, 26-year-old John Chau, was killed after he illegally attempted to make contact with the islanders three separate times and paid local fishermen to transport him to the island.[16][17][18]

History

[edit]The Onge, one of the other indigenous peoples of the Andamans, were aware of North Sentinel Island's existence; their traditional name for the island is Chia daaKwokweyeh.[2][19]: 362–363 They also have strong cultural similarities with what little has been remotely observed amongst the Sentinelese. However, Onges brought to North Sentinel Island by the British during the 19th century could not understand the language spoken by the North Sentinelese; as such, a significant period of separation is likely.[2][19]: 362–363

British visits

[edit]British surveyor John Ritchie observed "a multitude of lights" from an East India Company hydrographic survey vessel, the Diligent, as it passed by the island in 1771.[2][19]: 362–363 [20] Homfray, an administrator, travelled to the island in March 1867.[21]: 288

Towards the end of the same year's summer monsoon season, Nineveh, an Indian merchant ship, was wrecked on a reef near the island. The 106 surviving passengers and crewmen landed on the beach in the ship's boat and fended off attacks by the Sentinelese. They were eventually found by a Royal Navy rescue party.[19]: 362–363

Portman's expeditions

[edit]An expedition led by Maurice Vidal Portman, a government administrator who hoped to research the natives and their customs, landed on North Sentinel Island in January 1880. The group found a network of pathways and several small, abandoned villages. After several days, six Sentinelese, an elderly couple and four children, were taken to Port Blair. The colonial officer in charge of the operation wrote that the entire group

"sickened rapidly, and the old man and his wife died, so the four children were sent back to their home with quantities of presents".[2][20][21]: 288

A second landing was made by Portman on 27 August 1883 after the eruption of Krakatoa was mistaken for gunfire and interpreted as the distress signal of a ship. A search party landed on the island and left gifts before returning to Port Blair.[2][21]: 288 Portman visited the island several more times between January 1885 and January 1887.[21]: 288

After Indian independence

[edit]Early landings

[edit]

Indian exploratory parties under orders to establish friendly relations with the Sentinelese made brief landings on the island every few years beginning in 1967.[2] In 1975 Leopold III of Belgium, on a tour of the Andamans, was taken by local dignitaries for an overnight cruise to the waters off North Sentinel Island.[20]

Shipwrecks

[edit]The cargo ship MV Rusley ran aground on coastal reefs in mid-1977, and the MV Primrose did so on 2 August 1981. After the Primrose grounded on the North Sentinel Island reef, crewmen several days later noticed that some men carrying spears and arrows were building boats on the beach. The captain of Primrose radioed for an urgent drop of firearms so his crew could defend themselves. They did not receive any because a large storm stopped other ships from reaching them, but the heavy seas also prevented the islanders from approaching the ship. A week later, the crewmen were rescued by a helicopter under contract to the Indian Oil And Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC).[22]

The Sentinelese are known to have scavenged both shipwrecks for iron. Settlers from Port Blair also visited the sites to recover the cargo. In 1991, salvage operators were authorised to dismantle the ships.[19]: 342

First peaceful contact

[edit]The first peaceful contact with the Sentinelese was made by Triloknath Pandit, a director of the Anthropological Survey of India (AnSI), and his colleagues on 4 January 1991.[21]: 289 [23] Although Pandit and his colleagues were able to make repeated friendly contact, dropping coconuts and other gifts to the Sentinelese, no progress was made in understanding the Sentinelese language, and the Sentinelese repeatedly warned them off if they stayed too long. Indian visits to the island ceased in 1997.[2]

Indian Ocean earthquake and later hostile contact

[edit]The Sentinelese survived the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and its after-effects, including the tsunami and the uplifting of the island. Three days after the earthquake, an Indian government helicopter observed several islanders, who shot arrows and threw spears and stones at the helicopter.[2][19]: 362–363 [24] Although the tsunami disturbed the tribal fishing grounds, the Sentinelese appear to have adapted.[25]

In January 2006, two Indian fishermen, Sunder Raj and Pandit Tiwari, were fishing illegally in prohibited waters and were killed by the Sentinelese when their boat drifted too close to the island. There were no prosecutions.[12]

In November 2018, a 26-year old American Christian missionary named John Allen Chau,[26] who was trained and sent by Missouri-based All Nations,[27] was killed during an illegal trip to the restricted island where he planned to preach Christianity to the Sentinelese.[28] The 2023 documentary film The Mission discusses the incident. Seven individuals were taken into custody by Indian police on suspicion of abetting Chau's illegal access to the island.[27] Entering a radius of 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) around the island is illegal under Indian law.[26] The fishermen who illegally ferried Chau to North Sentinel said they saw tribesmen drag his body along a beach and bury it.[29] Despite efforts by Indian authorities, which involved a tense encounter with the tribe, Chau's body was not recovered.[27] Indian officials made several attempts to recover the body but eventually abandoned those efforts. An anthropologist involved in the case told The Guardian that the risk of a dangerous clash between investigators and the islanders was too great to justify any further attempts.[30]

Geography

[edit]North Sentinel lies 36 km (22 mi) west of the village of Wandoor in South Andaman Island,[2] 50 km (31 mi) west of Port Blair, and 59.6 km (37.0 mi) north of its counterpart South Sentinel Island. It has an area of about 59.67 km2 (23.04 sq mi) and a roughly square outline.[3]

North Sentinel is surrounded by coral reefs, and lacks natural harbours. The entire island, other than the shore, is forested.[31] There is a narrow, white-sand beach encircling the island, behind which the ground rises 20 metres (66 ft), and then gradually to between 46 and 122 metres (151 and 400 ft)[1][32]: 257 near the centre. Reefs extend around the island to between 0.9 and 1.5 km (0.5–0.8 nmi) from the shore.[1] A forested islet, Constance Island, also "Constance Islet",[1] is located about 600 metres (2,000 ft) off the southeast coastline, at the edge of the reef.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake tilted the tectonic plate under the island, lifting it by one to two metres (3 to 7 ft). Large tracts of the surrounding coral reefs were exposed and became permanently dry land or shallow lagoons, extending all the island's boundaries – by as much as one kilometre (3,300 ft) on the west and south sides – and uniting Constance Islet with the main island.[19]: 347 [25]

Flora and fauna

[edit]The island is largely covered in tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest. Due to the lack of surveys, the exact composition of the terrestrial flora and fauna remains unknown. In his 1880 expedition to the island, Maurice Vidal Portman reported an open, "park-like" jungle with numerous groves of bulletwood (Manilkara littoralis) trees, as well as huge, buttressed specimens of Malabar silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba).[33] Indian boar (Sus scrofa cristatus) are apparently found on the island and a major food source for the Sentinelese, with reports by Portman referring to a "huge heap" of pig skulls near a Sentinelese village.[34] The IUCN Red List lists North Sentinel as being an important habitat for coconut crabs (Birgus latro), which have been otherwise extirpated from most of the other Andaman Islands except from South Sentinel and Little Andaman.[35] North Sentinel Island, along with South Sentinel, is also considered a globally Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International, as despite the lack of surveys, the pristine habitat likely supports a diversity of birdlife.[36]

The marine life surrounding the island has also not been well surveyed. A large coral reef is known to circle the island, and mangroves are also known to fringe its banks. A c. 1999 report from divers near the island indicated that the reefs around the island were bleached in the 1998 El Niño, but had since seen new growth of coral. Sharks have allegedly also been seen in the waters off the island. Sea turtles likely also occur near the island, as Portman referred to them also being a major food source for the Sentinelese and one was sighted on a 1999 survey of the surrounding waters. Dolphins were also sighted on the same survey.[33][34]

Demographics

[edit]North Sentinel Island is inhabited by the Sentinelese, indigenous people who defend their voluntary isolation by force. Their population was estimated to be between 50 and 400 people in a 2012 report.[2] India's 2011 census indicates 15 residents[37] in 10 households, but that too was merely an estimate, described as a "wild guess" by The Times of India.[9]

Like the Jarawas whose numbers have been decreasing, the Sentinelese population would face the potential threats of infectious diseases to which they have no immunity, as well as violence from intruders. The Indian government has declared the entire island and its surrounding waters extending 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) from the island to be an exclusion zone to protect them from outside interference.[38]

Political status

[edit]The Andaman and Nicobar (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956 provides protection to the Sentinelese and other native tribes in the region.[39] The Andaman and Nicobar Administration stated in 2005 that they have no intention to interfere with the lifestyle or habitat of the Sentinelese and are not interested in pursuing any further contact with them or governing the island.[40] Although North Sentinel Island is not legally an autonomous administrative division of India, scholars have referred to it and its people as effectively autonomous,[41][42] or de-facto sovereign.[41][43]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Sailing Directions (Enroute), Pub. 173: India and the Bay of Bengal (PDF). Sailing Directions. United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2017. p. 274.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Weber, George. "Chapter 8: The Tribes; Part 6. The Sentineli". The Andamanese. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Forest Statistics" (PDF). Department of Environment & Forests Andaman & Nicobar Islands. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "Andaman and Nicobar Islands Census 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Mysterious 'lost' tribe kills US tourist". news.com.au. 22 November 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "A&N Islands – Pincodes". 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Registration Plate Numbers added to ISO Code

- ^ Mukerjee, Madhusree. "A visit to North Sentinel island: 'Please, please, please, let us not destroy this last haven'". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Ten Indian families world knows nothing about". The Times of India. 25 November 2018. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Chavez, Nicole (25 November 2018). "Indian authorities struggle to retrieve US missionary feared killed on remote island". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Village Code Directory: Andaman & Nicobar Islands" (PDF). Census of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b Foster, Peter (8 February 2006). "Stone Age tribe kills fishermen who strayed onto island". The Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Bonnett, Alastair (2014). Off The Map. Carreg Aurum Press. p. 82.

- ^ "Sentinelese Tribe: What Headlines Won't Tell You About Eco-Tourism". The Quint. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Jain, Bharti (23 November 2018). "US National Defied 3-tier Curbs & Caution to Reach Island". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "American tourist killed in Andaman island, 7 arrested". Indian Express. 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Police to probe who helped John Chau's trip to remote island in Andaman..." Reuters. 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "American on deadly trip to Indian island: 'God sheltered me'". MyNorthwest. New Delhi. AP. 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pandya, Vishvajit (2009). In the Forest: Visual and Material Worlds of Andamanese History (1858–2006). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4272-9. LCCN 2008943457. OCLC 371672686. OL 16952992W. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Goodheart, Adam (Autumn 2000). "The Last Island of the Savages". American Scholar. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Sarkar, Jayanta (1997). "Befriending the Sentinelese of the Andamans: A Dilemma". In Pfeffer, Georg; Behera, Deepak Kumar (eds.). Development Issues, Transition and Change. Contemporary Society: Tribal Studies. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-642-2. LCCN 97905535. OCLC 37770121. OL 324654M. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ "The strange mystery of North Sentinel Island". Unexplained Mysteries. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ McGirk, Tim (10 January 1993). "Islanders running out of isolation: Tim McGirk in the Andaman Islands reports on the fate of the Sentinelese". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (6 February 2010). "With one last breath, a people and language are gone". The New Zealand Herald. The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b Weber, George (2009). "The 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami". Archived from the original on 16 June 2013.

- ^ a b Slater, Joanna; Gowen, Annie (21 November 2018). "'God, I don't want to die,' U.S. missionary wrote before he was killed by remote tribe on Indian island". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b c "Police face-off with Sentinelese tribe as they struggle to recover slain missionary's body". News.com.au. AFP. 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Evans, Gareth; Hughes, Roland (24 November 2018). "John Allen Chau: What we could learn from remote tribes". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "John Allen Chau: 'Incredibly dangerous' to retrieve body from North Sentinel". BBC News. 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Safi, Michael; Giles, Denis (28 November 2018). "India has no plans to recover body of US missionary killed by tribe". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Weber, George. "Chapter 2: They Call it Home". The Andamanese. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012.

- ^ "North Sentinel". The Bay of Bengal Pilot. Admiralty. London: United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. 1887. p. 257. OCLC 557988334. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ a b Mukerjee, Madhusree (24 November 2018). "A visit to North Sentinel island: 'Please, please, please, let us not destroy this last haven'". Scroll.in. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ a b Portman, Maurice Vidal (1899). A history of our relations with the Andamanese. Robarts - University of Toronto. Calcutta Off. of the Superintendent of Govt. Print., India.

- ^ Cumberlidge, Neil (6 August 2018). "Birgus latro". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ "BirdLife Data Zone". datazone.birdlife.org. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ census, archive.org; accessed 2 April 2017.

- ^ number 23 (8 May 2015). "The Island Tribe Hostile To Outsiders Face Survival Threat". AnonHQ.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mazoomdaar, Jay (23 November 2018). "Do not disturb this Andaman island". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Bhaumik, Subir (5 March 2005). "Extinction threat for Andaman natives". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2005.

- ^ a b Kanchan Mukhopadhyay; M. Arbindo Singh (14 May 2007). "8. Some Observations on Tsunami and the Ang of the Andaman Islands". In V.R. Rao (ed.). Tsunami in South Asia: Studies of Impact on Communities of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Allied Publishers. p. 120. ISBN 9798184241890. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Wintle, Claire (2013). Colonial Collecting and Display: Encounters with Material Culture from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Berghahn Books. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-85745-942-8. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Ghose, Aruna, ed. (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: India. p. 627.

External links

[edit]- The Sentinelese People – history of the Sentinelese and of the island

- Brief factsheet about the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands by the Andaman & Nicobar Administration (archived 10 April 2009)

- "The Andaman Tribes: Victims of Development"

- Video clip from Survival International

- Photographs of the 1981 Primrose rescue