Alps

| Alps | |

|---|---|

Satellite view of the Alps | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mont Blanc |

| Elevation | 4,808.73 m (15,776.7 ft)[1] |

| Listing | List of mountain ranges |

| Coordinates | 45°49′58″N 06°51′54″E / 45.83278°N 6.86500°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,200 km (750 mi) |

| Width | 250 km (160 mi) |

| Area | 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | |

| Geography | |

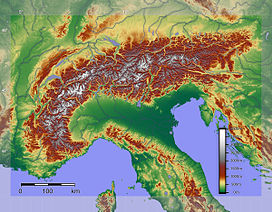

Relief of the Alps. See also map with international borders marked. | |

| Countries | |

| Range coordinates | 46°35′N 8°37′E / 46.58°N 8.62°E |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Alpine orogeny |

| Rock age | Tertiary |

| Rock types | |

The Alps (/ælps/)[a] are one of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe,[b][2] stretching approximately 1,200 km (750 mi) across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.[c][4]

The Alpine arch extends from Nice on the western Mediterranean to Trieste on the Adriatic and Vienna at the beginning of the Pannonian Basin. The mountains were formed over tens of millions of years as the African and Eurasian tectonic plates collided. Extreme shortening caused by the event resulted in marine sedimentary rocks rising by thrusting and folding into high mountain peaks such as Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn.

Mont Blanc spans the French–Italian border, and at 4,809 m (15,778 ft) is the highest mountain in the Alps. The Alpine region area contains 128 peaks higher than 4,000 m (13,000 ft).

The altitude and size of the range affect the climate in Europe; in the mountains, precipitation levels vary greatly and climatic conditions consist of distinct zones. Wildlife such as ibex live in the higher peaks to elevations of 3,400 m (11,155 ft), and plants such as edelweiss grow in rocky areas in lower elevations as well as in higher elevations.

Evidence of human habitation in the Alps goes back to the Palaeolithic era. A mummified man ("Ötzi"), determined to be 5,000 years old, was discovered on a glacier at the Austrian–Italian border in 1991.[5]

By the 6th century BC, the Celtic La Tène culture was well established. Hannibal notably crossed the Alps with a herd of elephants, and the Romans had settlements in the region. In 1800, Napoleon crossed one of the mountain passes with an army of 40,000. The 18th and 19th centuries saw an influx of naturalists, writers, and artists, in particular, the Romanticists, followed by the golden age of alpinism as mountaineers began to ascend the peaks of the Alps.

The Alpine region has a strong cultural identity. Traditional practices such as farming, cheesemaking, and woodworking still thrive in Alpine villages. However, the tourist industry began to grow early in the 20th century and expanded significantly after World War II, eventually becoming the dominant industry by the end of the century.

The Winter Olympic Games have been hosted in the Swiss, French, Italian, Austrian and German Alps. As of 2010,[update] the region is home to 14 million people and has 120 million annual visitors.[6]

Etymology and toponymy

[edit]

The English word Alps comes from the Latin Alpes.

The Latin word Alpes could possibly come from the adjective albus[7] ("white"), or could possibly come from the Greek goddess Alphito, whose name is related to alphita, the "white flour"; alphos, a dull white leprosy; and finally the Proto-Indo-European word *albʰós. Similarly, the river god Alpheus is also supposed to derive from the Greek alphos and means whitish.[8]

In his commentary on the Aeneid of Virgil, the late fourth-century grammarian Maurus Servius Honoratus says that all high mountains are called Alpes by Celts.[9]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Latin Alpes might derive from a pre-Indo-European word *alb "hill"; "Albania" is a related derivation. Albania, a name not native to the region known as the country of Albania, has been used as a name for several mountainous areas across Europe.

In Roman times, "Albania" was a name for the eastern Caucasus, while in the English languages "Albania" (or "Albany") was occasionally used as a name for Scotland,[10] although it is more likely derived from the Latin word albus,[7] the colour white.

In modern languages the term alp, alm, albe or alpe refers to a grazing pastures in the alpine regions below the glaciers, not the peaks.[11]

An alp refers to a high mountain pasture, typically near or above the tree line, where cows and other livestock are taken to be grazed during the summer months and where huts and hay barns can be found, sometimes constituting tiny hamlets. Therefore, the term "the Alps", as a reference to the mountains, is a misnomer.[12][13] The term for the mountain peaks varies by nation and language: words such as Horn, Kogel, Kopf, Gipfel, Spitze, Stock, and Berg are used in German-speaking regions; Mont, Pic, Tête, Pointe, Dent, Roche, and Aiguille in French-speaking regions; and Monte, Picco, Corno, Punta, Pizzo, or Cima in Italian-speaking regions.[14]

Geography

[edit]

The Alps are a crescent shaped geographic feature of central Europe that ranges in an 800 km (500 mi) arc (curved line) from east to west and is 200 km (120 mi) in width. The mean height of the mountain peaks is 2.5 km (1.6 mi).[15] The range stretches from the Mediterranean Sea north above the Po basin, extending through France from Grenoble, and stretching eastward through mid and southern Switzerland. The range continues onward toward Vienna, Austria, and southeast to the Adriatic Sea and Slovenia.[16][17][18]

To the south it dips into northern Italy and to the north extends to the southern border of Bavaria in Germany.[18] In areas like Chiasso, Switzerland, and Allgäu, Bavaria, the demarcation between the mountain range and the flatlands are clear; in other places such as Geneva, the demarcation is less clear.

The Alps are found in the following countries: Austria (28.7% of the range's area), Italy (27.2%), France (21.4%), Switzerland (13.2%), Germany (5.8%), Slovenia (3.6%), Liechtenstein (0.08%) and Monaco (0.001%).[19]

The highest portion of the range is divided by the glacial trough of the Rhône valley, from Mont Blanc to the Matterhorn and Monte Rosa on the southern side, and the Bernese Alps on the northern. The peaks in the easterly portion of the range, in Austria and Slovenia, are smaller than those in the central and western portions.[18]

The variances in nomenclature in the region spanned by the Alps make classification of the mountains and subregions difficult, but a general classification is that of the Eastern Alps and Western Alps with the divide between the two occurring in eastern Switzerland according to geologist Stefan Schmid,[11] near the Splügen Pass.

The highest peaks of the Western Alps and Eastern Alps, respectively, are Mont Blanc, at 4,810 m (15,780 ft),[20] and Piz Bernina, at 4,049 m (13,284 ft). The second-highest major peaks are Monte Rosa, at 4,634 m (15,203 ft), and Ortler,[21] at 3,905 m (12,810 ft), respectively.

A series of lower mountain ranges run parallel to the main chain of the Alps, including the French Prealps in France and the Jura Mountains in Switzerland and France. The secondary chain of the Alps follows the watershed from the Mediterranean Sea to the Wienerwald, passing over many of the highest and most well-known peaks in the Alps. From the Colle di Cadibona to Col de Tende it runs westwards, before turning to the northwest and then, near the Colle della Maddalena, to the north. Upon reaching the Swiss border, the line of the main chain heads approximately east-northeast, a heading it follows until its end near Vienna.[22]

The northeast end of the Alpine arc, directly on the Danube, which flows into the Black Sea, is the Leopoldsberg near Vienna. In contrast, the southeastern part of the Alps ends on the Adriatic Sea in the area around Trieste towards Duino and Barcola.[23]

Passes

[edit]

The Alps have been crossed for war and commerce, and by pilgrims, students and tourists. Crossing routes by road, train, or foot are known as passes, and usually consist of depressions in the mountains in which a valley leads from the plains and hilly pre-mountainous zones.[24]

In the medieval period hospices were established by religious orders at the summits of many of the main passes.[13] The most important passes are the Col de l'Iseran (the highest), the Col Agnel, the Brenner Pass, the Mont-Cenis, the Great St. Bernard Pass, the Col de Tende, the Gotthard Pass, the Semmering Pass, the Simplon Pass, and the Stelvio Pass.[25]

Crossing the Italian-Austrian border, the Brenner Pass separates the Ötztal Alps and Zillertal Alps and has been in use as a trading route since the 14th century. The lowest of the Alpine passes at 985 m (3,232 ft), the Semmering crosses from Lower Austria to Styria; since the 12th century when a hospice was built there, it has seen continuous use. A railroad with a tunnel 1.6 km (1 mi) long was built along the route of the pass in the mid-19th century. With a summit of 2,469 m (8,100 ft), the Great St Bernard Pass is one of the highest in the Alps, crossing the Italian-Swiss border east of the Pennine Alps along the flanks of Mont Blanc. The pass was used by Napoleon Bonaparte to cross 40,000 troops in 1800.[26]

The Mont Cenis pass has been a major commercial and military road between Western Europe and Italy. The pass was crossed by many troops on their way to the Italian peninsula. From Constantine I, Pepin the Short and Charlemagne to Henry IV, Napoléon and more recently the German Gebirgsjägers during World War II.[27]

Now the pass has been supplanted by the Fréjus Highway Tunnel (opened 1980) and Rail Tunnel (opened 1871).[28]

The Saint Gotthard Pass crosses from Central Switzerland to Ticino; in 1882 the 15 km-long (9.3 mi) Saint Gotthard Railway Tunnel was opened connecting Lucerne in Switzerland, with Milan in Italy. 98 years later followed Gotthard Road Tunnel (16.9 km (10.5 mi) long) connecting the A2 motorway in Göschenen on the north side with Airolo on the south side, exactly like the railway tunnel.[29]

On 1 June 2016 the world's longest railway tunnel, the Gotthard Base Tunnel, was opened, which connects Erstfeld in canton of Uri with Bodio in canton of Ticino by two single tubes of 57.1 km (35.5 mi).[30]

It is the first tunnel that traverses the Alps on a flat route.[31]

From 11 December 2016, it has been part of the regular railway timetable and used hourly as standard ride between Basel/Lucerne/Zürich and Bellinzona/Lugano/Milan.[32]

The highest pass in the alps is the Col de l'Iseran in Savoy (France) at 2,770 m (9,088 ft), followed by the Stelvio Pass in northern Italy at 2,756 m (9,042 ft); the road was built in the 1820s.[25]

Highest mountains

[edit]

The Union Internationale des Associations d'Alpinisme (UIAA) has defined a list of 82 "official" Alpine summits that reach at least 4,000 m (13,123 ft).[33] The list includes not only mountains, but also subpeaks with little prominence that are considered important mountaineering objectives. Below are listed the 29 "four-thousanders" with at least 300 m (984 ft) of prominence.

While Mont Blanc was first climbed in 1786 and the Jungfrau in 1811, most of the Alpine four-thousanders were climbed during the second half of the 19th century, notably Piz Bernina (1850), the Dom (1858), the Grand Combin (1859), the Weisshorn (1861) and the Barre des Écrins (1864); the ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865 marked the end of the golden age of alpinism. Karl Blodig (1859–1956) was among the first to successfully climb all the major 4,000 m peaks. He completed his series of ascents in 1911.[34] Many of the big Alpine three-thousanders were climbed in the early 19th century, notably the Grossglockner (1800) and the Ortler (1804), although some of them were climbed only much later, such at Mont Pelvoux (1848), Monte Viso (1861) and La Meije (1877).

The first British Mont Blanc ascent by a man was in 1788; the first ascent by a woman was in 1808. By the mid-1850s Swiss mountaineers had ascended most of the peaks and were eagerly sought as mountain guides. Edward Whymper reached the top of the Matterhorn in 1865 (after seven attempts), and in 1938 the last of the six great north faces of the Alps was climbed with the first ascent of the Eiger Nordwand (north face of the Eiger).[35]

| Name | Height | Name | Height | Name | Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mont Blanc | 4,810 m (15,781 ft) | Grandes Jorasses | 4,208 m (13,806 ft) | Barre des Écrins | 4,102 m (13,458 ft) |

| Monte Rosa | 4,634 m (15,203 ft) | Alphubel | 4,206 m (13,799 ft) | Schreckhorn | 4,078 m (13,379 ft) |

| Dom | 4,546 m (14,915 ft) | Rimpfischhorn | 4,199 m (13,776 ft) | Ober Gabelhorn | 4,063 m (13,330 ft) |

| Lyskamm | 4,532 m (14,869 ft) | Aletschhorn | 4,194 m (13,760 ft) | Gran Paradiso | 4,061 m (13,323 ft) |

| Weisshorn | 4,505 m (14,780 ft) | Strahlhorn | 4,190 m (13,747 ft) | Piz Bernina | 4,048 m (13,281 ft) |

| Matterhorn | 4,478 m (14,692 ft) | Dent d'Hérens | 4,173 m (13,691 ft) | Gross Fiescherhorn | 4,049 m (13,284 ft) |

| Dent Blanche | 4,357 m (14,295 ft) | Breithorn | 4,160 m (13,648 ft) | Gross Grünhorn | 4,043 m (13,264 ft) |

| Grand Combin | 4,309 m (14,137 ft) | Jungfrau | 4,158 m (13,642 ft) | Weissmies | 4,013 m (13,166 ft) |

| Finsteraarhorn | 4,274 m (14,022 ft) | Aiguille Verte | 4,122 m (13,524 ft) | Lagginhorn | 4,010 m (13,156 ft) |

| Zinalrothorn | 4,221 m (13,848 ft) | Mönch | 4,110 m (13,484 ft) | list continued here | |

Geology and orogeny

[edit]Important geological concepts were established as naturalists began studying the rock formations of the Alps in the 18th century. In the mid-19th century, the now-defunct idea of geosynclines was used to explain the presence of "folded" mountain chains. This theory was replaced in the mid-20th century by the theory of plate tectonics.[37]

The formation of the Alps (the Alpine orogeny) was an episodic process that began about 300 million years ago.[39] In the Paleozoic Era the Pangaean supercontinent consisted of a single tectonic plate; it broke into separate plates during the Mesozoic Era and the Tethys sea developed between Laurasia and Gondwana during the Jurassic Period.[37] The Tethys was later squeezed between colliding plates causing the formation of mountain ranges called the Alpide belt, from Gibraltar through the Himalayas to Indonesia—a process that began at the end of the Mesozoic and continues into the present. The formation of the Alps was a segment of this orogenic process,[37] caused by the collision between the African and the Eurasian plates[40] that began in the late Cretaceous Period.[41]

Under extreme compressive stresses and pressure, marine sedimentary rocks were uplifted, forming characteristic recumbent folds, and thrust faults.[42] As the rising peaks underwent erosion, a layer of marine flysch sediments was deposited in the foreland basin, and the sediments became involved in younger folds as the orogeny progressed. Coarse sediments from the continual uplift and erosion were later deposited in foreland areas north of the Alps.[40] These regions in Switzerland and Bavaria are well-developed, containing classic examples of flysch, which is sedimentary rock formed during mountain building.[43]

The Alpine orogeny occurred in ongoing cycles through to the Paleogene causing differences in folded structures, with a late-stage orogeny causing the development of the Jura Mountains.[44] A series of tectonic events in the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods caused different paleogeographic regions.[44] The Alps are subdivided by different lithology (rock composition) and nappe structures according to the orogenic events that affected them.[11] The geological subdivision differentiates the Western, Eastern Alps, and Southern Alps: the Helveticum in the north, the Penninicum and Austroalpine system in the centre and, south of the Periadriatic Seam, the Southern Alpine system.[45]

According to geologist Stefan Schmid, because the Western Alps underwent a metamorphic event in the Cenozoic Era while the Austroalpine peaks underwent an event in the Cretaceous Period, the two areas show distinct differences in nappe formations.[44] Flysch deposits in the Southern Alps of Lombardy probably occurred in the Cretaceous or later.[44]

Peaks in France, Italy and Switzerland lie in the "Houillière zone", which consists of basement with sediments from the Mesozoic Era.[45] High "massifs" with external sedimentary cover are more common in the Western Alps and were affected by Neogene Period thin-skinned thrusting whereas the Eastern Alps have comparatively few high peaked massifs.[43] Similarly the peaks in eastern Switzerland extending to western Austria (Helvetic nappes) consist of thin-skinned sedimentary folding that detached from former basement rock.[46]

In simple terms, the structure of the Alps consists of layers of rock of European, African, and oceanic (Tethyan) origin.[47] The bottom nappe structure is of continental European origin, above which are stacked marine sediment nappes, topped off by nappes derived from the African plate.[48] The Matterhorn is an example of the ongoing orogeny and shows evidence of great folding. The tip of the mountain consists of gneisses from the African plate; the base of the peak, below the glaciated area, consists of European basement rock. The sequence of Tethyan marine sediments and their oceanic basement is sandwiched between rock derived from the African and European plates.[38]

The core regions of the Alpine orogenic belt have been folded and fractured in such a manner that erosion produced the characteristic steep vertical peaks of the Swiss Alps that rise seemingly straight out of the foreland areas.[41] Peaks such as Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, and high peaks in the Pennine Alps, the Briançonnais, and Hohe Tauern consist of layers of rock from the various orogenies including exposures of basement rock.[49]

Due to the ever-present geologic instability, earthquakes continue in the Alps to this day.[50] Typically, the largest earthquakes in the alps have been between magnitude 6 and 7 on the Richter scale.[51] Geodetic measurements show ongoing topographic uplift at rates of up to about 2.5 mm per year in the North, Western and Central Alps, and at ~1 mm per year in the Eastern and South-Western Alps.[52] The underlying mechanisms that jointly drive the present-day uplift pattern are the isostatic rebound due to the melting of the last glacial maximum ice-cap or long-term erosion, detachment of the Western Alpine subducting slab, mantle convection as well as ongoing horizontal convergence between Africa and Europe, but their relative contributions to the uplift of the Alps are difficult to quantify and likely to vary significantly in space and time.[52]

Minerals

[edit]The Alps are a source of minerals that have been mined for thousands of years. In the 8th to 6th centuries, BC during the Hallstatt culture, Celtic tribes mined copper; later the Romans mined gold for coins in the Bad Gastein area. Erzberg in Styria furnishes high-quality iron ore for the steel industry. Crystals, such as cinnabar, amethyst, and quartz, are found throughout much of the Alpine region. The cinnabar deposits in Slovenia are a notable source of cinnabar pigments.[53]

Alpine crystals have been studied and collected for hundreds of years and began to be classified in the 18th century. Leonhard Euler studied the shapes of crystals, and by the 19th-century crystal hunting was common in Alpine regions. David Friedrich Wiser amassed a collection of 8000 crystals that he studied and documented. In the 20th century Robert Parker wrote a well-known work about the rock crystals of the Swiss Alps; at the same period a commission was established to control and standardize the naming of Alpine minerals.[54]

Glaciers

[edit]

In the Miocene Epoch the mountains underwent severe erosion because of glaciation,[41] which was noted in the mid-19th century by naturalist Louis Agassiz who presented a paper proclaiming the Alps were covered in ice at various intervals—a theory he formed when studying rocks near his Neuchâtel home which he believed originated to the west in the Bernese Oberland. Because of his work he came to be known as the "father of the ice-age concept" although other naturalists before him put forth similar ideas.[55]

Agassiz studied glacier movement in the 1840s at the Unteraar Glacier where he found the glacier moved 100 m (328 ft) per year, more rapidly in the middle than at the edges. His work was continued by other scientists and now a permanent laboratory exists inside a glacier under the Jungfraujoch, devoted exclusively to the study of Alpine glaciers.[55]

Glaciers pick up rocks and sediment with them as they flow. This causes erosion and the formation of valleys over time. The Inn valley is an example of a valley carved by glaciers during the ice ages with a typical terraced structure caused by erosion. Eroded rocks from the most recent ice age lie at the bottom of the valley while the top of the valley consists of erosion from earlier ice ages.[55] Glacial valleys have characteristically steep walls (reliefs); valleys with lower reliefs and talus slopes are remnants of glacial troughs or previously infilled valleys.[56] Moraines, piles of rock picked up during the movement of the glacier, accumulate at edges, centre, and the terminus of glaciers.[55]

Alpine glaciers can be straight rivers of ice, long sweeping rivers, spread in a fan-like shape (Piedmont glaciers), and curtains of ice that hang from vertical slopes of the mountain peaks. The stress of the movement causes the ice to break and crack loudly, perhaps explaining why the mountains were believed to be home to dragons in the medieval period. The cracking creates unpredictable and dangerous crevasses, often invisible under new snowfall, which causes the greatest danger to mountaineers.[57]

Glaciers end in ice caves (the Rhône Glacier), by trailing into a lake or river, or by shedding snowmelt on a meadow. Sometimes a piece of glacier will detach or break resulting in flooding, property damage, and loss of life.[57]

High levels of precipitation cause the glaciers to descend to permafrost levels in some areas whereas in other, more arid regions, glaciers remain above about the 3,500 m (11,483 ft) level.[58] The 1,817 km2 (702 sq mi) of the Alps covered by glaciers in 1876 had shrunk to 1,342 km2 (518 sq mi) by 1973, resulting in decreased river run-off levels.[59] Forty percent of the glaciation in Austria has disappeared since 1850, and 30% of that in Switzerland.[60]

Although the Alpine topography shows marked glacial morphologies,[61] the mechanisms by which glacial reshaping occurs are unclear. Numerical modeling suggests that glacial erosion propagates from low elevations to high elevations leading to an early increase of local relief followed by lowering of the mean orogen elevation.[62]

Rivers and lakes

[edit]

The Alps provide lowland Europe with drinking water, irrigation, and hydroelectric power.[64] Although the area is only about 11% of the surface area of Europe, the Alps provide up to 90% of water to lowland Europe, particularly to arid areas and during the summer months. Cities such as Milan depend on 80% of water from Alpine runoff.[16][65][66] Water from the rivers is used in at least 550 hydroelectricity power plants, considering only those producing at least 10MW of electricity.[67]

Major European rivers flow from the Alps, such as the Rhine, the Rhône, the Inn, and the Po, all of which have headwaters in the Alps and flow into neighbouring countries, finally emptying into the North Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea. Other rivers such as the Danube have major tributaries flowing into them that originate in the Alps.[16]

The Rhône is second to the Nile as a freshwater source to the Mediterranean Sea; the river begins as glacial meltwater, flows into Lake Geneva, and from there to France where one of its uses is to cool nuclear power plants.[68] The Rhine originates in a 30 km2 (12 sq mi) area in Switzerland and represents almost 60% of water exported from the country.[68] Tributary valleys, some of which are complicated, channel water to the main valleys which can experience flooding during the snowmelt season when rapid runoff causes debris torrents and swollen rivers.[69]

The rivers form lakes, such as Lake Geneva, a crescent-shaped lake crossing the Swiss border with Lausanne on the Swiss side and the town of Evian-les-Bains on the French side. In Germany, the medieval St. Bartholomew's chapel was built on the south side of the Königssee, accessible only by boat or by climbing over the abutting peaks.[70]

Additionally, the Alps have led to the creation of large lakes in Italy. For instance, the Sarca, the primary inflow of Lake Garda, originates in the Italian Alps.[71] The Italian Lakes are a popular tourist destination since the Roman Era for their mild climate.

Scientists have been studying the impact of climate change and water use. For example, each year more water is diverted from rivers for snowmaking in the ski resorts, the effect of which is yet unknown. Furthermore, the decrease of glaciated areas combined with a succession of winters with lower-than-expected precipitation may have a future impact on the rivers in the Alps as well as an effect on the water availability to the lowlands.[65][72]

Climate

[edit]The Alps are a classic example of what happens when a temperate area at lower altitude gives way to higher-elevation terrain. Elevations around the world that have cold climates similar to those of the polar regions have been called Alpine. A rise from sea level into the upper regions of the atmosphere causes the temperature to decrease (see adiabatic lapse rate). The effect of mountain chains on prevailing winds is to carry warm air belonging to the lower region into an upper zone, where it expands in volume at the cost of a proportionate loss of temperature, often accompanied by precipitation in the form of snow or rain.[73] The height of the Alps is sufficient to divide the weather patterns in Europe into a wet north and dry south because moisture is sucked from the air as it flows over the high peaks.[74]

The severe weather in the Alps has been studied since the 18th century; particularly the weather patterns such as the seasonal foehn wind. Numerous weather stations were placed in the mountains early in the early 20th century, providing continuous data for climatologists.[15] Some of the valleys are quite arid such as the Aosta Valley in Italy, the Maurienne in France, the Valais in Switzerland, and northern Tyrol.[15]

The areas that are not arid and receive high precipitation experience periodic flooding from rapid snowmelt and runoff.[69] The mean precipitation in the Alps ranges from a low of 2,600 mm (100 in) per year to 3,600 mm (140 in) per year, with the higher levels occurring at high altitudes. At altitudes between 1,000 and 3,000 m (3,300 and 9,800 ft), snowfall begins in November and accumulates through to April or May when the melt begins. Snow lines vary from 2,400 to 3,000 m (7,900 to 9,800 ft), above which the snow is permanent and the temperatures hover around the freezing point even during July and August. High-water levels in streams and rivers peak in June and July when the snow is still melting at the higher altitudes.[75]

The Alps are split into five climatic zones, each with different vegetation. The climate, plant life, and animal life vary among the different sections or zones of the mountains. The lowest zone is the colline zone, which exists between 500 and 1,000 m (1,600 and 3,300 ft), depending on the location. The montane zone extends from 800 to 1,700 m (2,600 to 5,600 ft), followed by the sub-Alpine zone from 1,600 to 2,400 m (5,200 to 7,900 ft). The Alpine zone, extending from tree line to the snow line, is followed by the glacial zone, which covers the glaciated areas of the mountain. Climatic conditions show variances within the same zones; for example, weather conditions at the head of a mountain valley, extending directly from the peaks, are colder and more severe than those at the mouth of a valley which tend to be less severe and receive less snowfall.[76]

- Climate change

Various models of climate change have been projected into the 22nd century for the Alps, with an expectation that a trend toward increased temperatures will have an effect on snowfall, snowpack, glaciation, and river runoff.[78][79] Significant changes, of both natural and anthropogenic origins, have already been diagnosed from observations,[80][81][82] including a 5.6% reduction per decade in snow cover duration over the last 50 years, which also highlights climate change adaptation needs due to impacts on the climate and regional socio-economic activities.[77]

Ecology

[edit]Flora

[edit]

Thirteen thousand species of plants have been identified in the Alpine regions.[6] Alpine plants are grouped by habitat and soil type which can be limestone or non-calcareous. The habitats range from meadows, bogs, and woodland (deciduous and coniferous) areas to soil-less scree and moraines, and rock faces and ridges.[12] A natural vegetation limit with altitude is given by the presence of the chief deciduous trees—oak, beech, ash and sycamore maple. These do not reach the same elevation, nor are they often found growing together, but their upper limit corresponds accurately enough to the change from a temperate to a colder climate that is further proved by a change in the presence of wild herbaceous vegetation.[83] This limit usually lies about 1,200 m (3,900 ft) above the sea on the north side of the Alps, but on the southern slopes it often rises to 1,500 m (4,900 ft), sometimes even to 1,700 m (5,600 ft).[84]

Above the forestry, there is often a band of dwarf pine trees (Pinus mugo), which is in turn superseded by Alpenrosen, dwarf shrubs, typically Rhododendron ferrugineum (on acid soils) or Rhododendron hirsutum (on alkaline soils).[85] Although Alpenrose prefers acidic soil, the plants are found throughout the region.[12] Above the tree line is the area defined as "alpine" where in the alpine meadow plants are found that have adapted well to harsh conditions of cold temperatures, aridity, and high altitudes. The alpine area fluctuates greatly because of regional fluctuations in tree lines.[86]

Alpine plants such as the Alpine gentian grow in abundance in areas such as the meadows above the Lauterbrunnental. Gentians are named after the Illyrian king Gentius, and 40 species of the early-spring blooming flower grow in the Alps, in a range of 1,500 to 2,400 m (4,900 to 7,900 ft).[87] Writing about the gentians in Switzerland D. H. Lawrence described them as "darkening the day-time, torch-like with the smoking blueness of Pluto's gloom."[88] Gentians tend to "appear" repeatedly as the spring blooming takes place at progressively later dates, moving from the lower altitude to the higher altitude meadows where the snow melts much later than in the valleys. On the highest rocky ledges, the spring flowers bloom in the summer.[12]

At these higher altitudes, the plants tend to form isolated cushions. In the Alps, several species of flowering plants have been recorded above 4,000 m (13,000 ft), including Ranunculus glacialis, Androsace alpina and Saxifraga biflora. Eritrichium nanum, commonly known as the King of the Alps, is the most elusive of the alpine flowers, growing on rocky ridges at 2,600 to 3,750 m (8,530 to 12,300 ft).[89] Perhaps the best known of the alpine plants is Edelweiss which grows in rocky areas and can be found at altitudes as low as 1,200 m (3,900 ft) and as high as 3,400 m (11,200 ft).[12] The plants that grow at the highest altitudes have adapted to conditions by specialization such as growing in rock screes that give protection from winds.[90]

The extreme and stressful climatic conditions give way to the growth of plant species with secondary metabolites important for medicinal purposes. Origanum vulgare, Prunella vulgaris, Solanum nigrum, and Urtica dioica are some of the more useful medicinal species found in the Alps.[91] Human interference has nearly exterminated the trees in many areas, and, except for the beech forests of the Austrian Alps, forests of deciduous trees are rarely found after the extreme deforestation between the 17th and 19th centuries.[92] The vegetation has changed since the second half of the 20th century, as the high alpine meadows cease to be harvested for hay or used for grazing which eventually might result in a regrowth of the forest. In some areas, the modern practice of building ski runs by mechanical means has destroyed the underlying tundra from which the plant life cannot recover during the non-skiing months, whereas areas that still practice a natural piste type of ski slope building preserve the fragile underlayers.[90]

Fauna

[edit]The Alps are a habitat for 30,000 species of wildlife, ranging from the tiniest snow fleas to large birds like ostriches to brown bears, many of which have made adaptations to the harsh cold conditions and high altitudes to the point that some only survive in specific micro-climates either directly above or below the snow line.[6][93]

The largest mammal to live in the highest altitudes are the alpine ibex, which have been sighted as high as 3,000 m (9,800 ft). The ibex live in caves and descend to eat the succulent alpine grasses.[94] Classified as antelopes,[12] chamois are smaller than ibex and found throughout the Alps, living above the tree line and are common in the entire alpine range.[95] Areas of the eastern Alps are still home to brown bears. In Switzerland the canton of Bern was named for the bears but the last bear is recorded as having been killed in 1792 above Kleine Scheidegg by three hunters from Grindelwald.[96]

Many rodents such as voles live underground. Marmots live almost exclusively above the tree line as high as 2,700 m (8,900 ft). They hibernate in large groups to provide warmth,[97] and can be found in all areas of the Alps, in large colonies they build beneath the alpine pastures.[12] Golden eagles and bearded vultures are the largest birds to be found in the Alps; they nest high on rocky ledges and can be found at altitudes of 2,400 m (7,900 ft). The most common bird is the alpine chough which can be found scavenging at climber's huts or the Jungfraujoch, a high-altitude tourist destination.[98]

Reptiles such as adders and vipers live up to the snow line; because they cannot bear the cold temperatures they hibernate underground and soak up the warmth on rocky ledges.[99] The high-altitude Alpine salamanders have adapted to living above the snow line by giving birth to fully developed young rather than laying eggs. Brown trout can be found in the streams up to the snow line.[99] Molluscs such as the wood snail live up the snow line. Popularly gathered as food, the snails are now protected.[100]

Several species of moths live in the Alps, some of which are believed to have evolved in the same habitat up to 120 million years ago, long before the Alps were created. Blue butterflies can commonly be seen drinking from the snowmelt; some species of blues fly as high as 1,800 m (5,900 ft).[101] The butterflies tend to be large, such as those from the swallowtail Parnassius family, with a habitat that ranges to 1,800 m (5,900 ft). Twelve species of beetles have habitats up to the snow line; the most beautiful and formerly collected for its colours but now protected is Rosalia alpina.[102] Spiders, such as the large wolf spider, live above the snow line and can be seen as high as 400 m (1,300 ft). Scorpions can be found in the Italian Alps.[100]

Some of the species of moths and insects show evidence of having been indigenous to the area from as long ago as the Alpine orogeny. In Émosson in Valais, Switzerland, dinosaur tracks were found in the 1970s, dating probably from the Triassic Period.[103]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

When the ice melted after the Würm glaciation, paleolithic settlements were established along the lake shores and in cave systems. Evidence of human habitation has been found in caves near the Vercors Cave System, close to Grenoble and Echirolles. In Austria, the Mondsee lake shows evidence of houses built on piles. Standing stones have been found in the Alpine areas of France and Italy. About 200,000 drawings and etchings have been documented, and are known as the Rock Drawings in Valcamonica.[104]

A mummy of a neolithic human, known as Ötzi, was discovered on the Similaun. His clothing lets modern people assume that he was an alpine farmer, while the location and manner of his death suggests that Ötzi was traveling.[105] Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of Ötzi, has shown that he belongs to the K1 subclade.[106]

From the 13th to the 6th century BC much of the Alps was settled by the Germanic peoples, Lombards, Alemanni, Bavarii, and Franks.[107] Celt tribes settled in modern-day Switzerland between 1500 and 1000 BC. The Raeti lived in the eastern regions, while the west was occupied by the Helvetii and the Allobroges settled in the Rhône valley and in Savoy. The Ligures and Adriatic Veneti lived in Northwest Italy and Triveneto respectively. The Celts mined salt in areas such as Salzburg, where evidence was found of the Hallstatt culture.[104] By the 6th century BC the La Tène culture was well established in the region,[108] and became known for high quality Celtic art.[109]

Between 430 and 400 BC prolonged warfare in the Alps resulted in the devastation of agricultural land and human settlements, ultimately triggering the enslavement of men, women, and children, goods had to be imported as a result. The Etruscan civilization responded to raids by the Massalia and acquired absolute control over the Alpine trade routes. Aggressors in modern-day Italy were dealt with and an alliance was formed with the Celts. The grip of the Etruscan settlements broke down, as the Roman political system expanded, so as to take control over Alpine trade routes that connected human settlements in the Alps with settlements in the Mediterranean.[110]

During the Second Punic War in 218 BC, the Carthage general Hannibal initiated one of the most celebrated achievements of any military force in ancient warfare, recorded as Hannibal crossing the Alps.[111] The Roman people built roads along the Alpine mountain passes, which continued to be used through the medieval period. Roman road markers can still be found on the Alpine mountain passes.[112]

During the Gallic Wars in 58 BC Julius Caesar defeated the Helvetii. The Rhaetian continued to resist but their territory was eventually conquered when the Romans crossed the Danube valley and defeated the Brigantes.[113] The Romans built settlements in the Alps. In towns such as Aosta, Martigny, Lausanne, and Partenkirchen remains of villas, arenas, and temples have been discovered.[114]

Christianity, feudalism, and Napoleonic wars

[edit]

Christianity was established in the Alps by the Roman people. Monasteries and churches were constructed, even at high Alpine altitudes. The Franks expanded their Carolingian Empire, while the Baiuvarii introduced feudalism in the eastern Alps. The construction of castles in the Alps supported the growing number of dukedoms and kingdoms. Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento, still has intricate frescoes, and excellent examples of Gothic art. The Château de Chillon is preserved as an example of medieval architecture.[115] There are several important alpine saints and one such one is Saint Maurice.[116] Much of the medieval period was a time of power struggles between competing dynasties such as the House of Savoy, the Visconti of Milan, and the House of Habsburg.[117]

The Great St Bernard Hospice, built in the 9th or 10th centuries, at the summit of the Great Saint Bernard Pass was a shelter for humans and destination for pilgrims.[118] In 1291, to protect themselves from incursions by the House of Habsburg, four Alpine cantons drew up the Federal Charter of 1291, which is considered to be a declaration of independence from neighboring kingdoms. After a series of battles fought in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries, more cantons joined the confederacy and by the 16th century, Switzerland was established as a sovereign state.[119]

In the Alps, the War of the Spanish Succession fallout resulted in a 1713 treaty, part of the Peace of Utrecht, which relocated the Western Alps border along the watersheds. Historically, the Alps were used to determine the borders of political and administrative gangs, but the Peace of Utrecht was the first significant body of treaty that considered geographical conditions. The Alps were carved up and borders were agreed, so that enclaves in the Alps could be eliminated.[120]

During the Napoleonic Wars in the late 18th century and early 19th century, Napoleon annexed territory formerly controlled by the House of Habsburg, and the House of Savoy. In 1798, the Helvetic Republic was established, two years later an army across the Great St Bernard Pass.[121] In 1799 the Russian imperial military engaged the revolutionary French army in the Alps, this episode has been recorded as significant achievement in mountain warfare.[122] In October 1799 the troops commanded by Alexander Suvorov were surrounded in the Alps by much larger French troops. The Russian troops broke out, mauled the French troops, and retreated through the Panix Pass.[123]

After the fall of Napoleon, many alpine countries developed heavy protections to prevent further invasion. Thus, Savoy built a series of fortifications to protect the major alpine passes, such as the col du Mont-Cenis, which was crossed by Charlemagne to obliterate the Lombards.

In the 19th century, the monasteries built in the Alps to shelter humans became tourist destinations. The Benedictines had built monasteries in Lucerne, and Oberammergau. The Cistercians built their temple at Lake Constance. Meanwhile, the Augustinians maintained abbeys in Savoy and one in Interlaken.[124]

Exploration

[edit]

Radiocarbon-dated charcoal placed around 50,000 years ago was found in the Drachloch (Dragon's Hole) cave above the village of Vattis in the canton of St. Gallen, proving that the high peaks were visited by prehistoric people. Seven bear skulls from the cave may have been buried by the same prehistoric people.[125] The peaks, however, were mostly ignored except for a few notable examples, and long left to the exclusive attention of the people of the adjoining valleys.[126][127] The mountain peaks were seen as terrifying, the abode of dragons and demons, to the point that people blindfolded themselves to cross the Alpine passes.[128] The glaciers remained a mystery and many still believed the highest areas to be inhabited by dragons.[129]

Charles VII of France ordered his chamberlain to climb Mont Aiguille in 1356. The knight reached the summit of Rocciamelone where he left a bronze triptych of three crosses, a feat which he conducted with the use of ladders to traverse the ice.[130] In 1492, Antoine de Ville climbed Mont Aiguille, without reaching the summit, an experience he described as "horrifying and terrifying."[127] Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by variations of light in the higher altitudes, and climbed a mountain—scholars are uncertain which one; some believe it may have been Monte Rosa. From his description of a "blue like that of a gentian" sky it is thought that he reached a significantly high altitude.[131] In the 18th century four Chamonix men almost made the summit of Mont Blanc but were overcome by altitude sickness and snowblindness.[132]

Conrad Gessner was the first naturalist to ascend the mountains in the 16th century, to study them, writing that in the mountains he found the "theatre of the Lord".[133] By the 19th century more naturalists began to arrive to explore, study and conquer the high peaks.[134] Two men who first explored the regions of ice and snow were Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740–1799) in the Pennine Alps,[135] and the Benedictine monk of Disentis Placidus a Spescha (1752–1833).[134] Born in Geneva, Saussure was enamoured with the mountains from an early age; he left a law career to become a naturalist and spent many years trekking through the Bernese Oberland, the Savoy, the Piedmont and Valais, studying the glaciers and geology, as he became an early proponent of the theory of rock upheaval.[136] Saussure, in 1787, was a member of the third ascent of Mont Blanc—today the summits of all the peaks have been climbed.[35]

The Romantics and Alpinists

[edit]

Albrecht von Haller's poem Die Alpen, published in 1732 described the mountains as an area of mythical purity.[137] Jean-Jacques Rousseau presented the Alps as a place of allure and beauty, in his novel Julie, or the New Heloise, published in 1761. Later the first wave of Romanticism such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and J. M. W. Turner came to admire the Alpine scenery;[138] Wordsworth visited the area in 1790, writing of his experiences in The Prelude (1799). Schiller later wrote the play William Tell (1804), which tells the story of the legendary Swiss marksman William Tell as part of the greater Swiss struggle for independence from the Habsburg Empire in the early 14th century. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Alpine countries began to see an influx of poets, artists, and musicians,[139] as visitors came to experience the sublime effects of monumental nature.[140]

In 1816, Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Shelley visited Geneva and all three were inspired by the scenery in their writings.[139] During these visits Shelley wrote the poem "Mont Blanc", Byron wrote "The Prisoner of Chillon" and the dramatic poem Manfred, and Mary Shelley, who found the scenery overwhelming, conceived the idea for the novel Frankenstein in her villa on the shores of Lake Geneva amid a thunderstorm. When Coleridge travelled to Chamonix, he declaimed, in defiance of Shelley, who had signed himself "Atheos" in the guestbook of the Hotel de Londres near Montenvers,[141] "Who would be, who could be an atheist in this valley of wonders".[142]

By the mid-19th century scientists began to arrive en masse to study the geology and ecology of the region.[143]

From the beginning of the 19th century, the tourism and mountaineering development of the Alps began. In the early years of the "golden age of alpinism" initially scientific activities were mixed with sport, for example by the physicist John Tyndall, with the first ascent of the Matterhorn by Edward Whymper being the highlight. In the later years, the "silver age of alpinism", the focus was on mountain sports and climbing. The first president of the Alpine Club, John Ball, is considered the discoverer of the Dolomites, which for decades were the focus of climbers like Paul Grohmann, Michael Innerkofler and Angelo Dibona.[144][145][146]

The Nazis

[edit]

In autumn 1932, Adolf Hitler commissioned the first of a series of refurbishments, which eventually turned a mountain cottage, later named Berghof, into a fortified citadel. This domestic, but representative, fortification had two small bedrooms, and a full bathroom, planned by the Munich architect and NSDAP member Josef Neumaier. Guests, such as Rudolf Hess, stayed over, sleeping in tents or over the garage.[147]

The Alps, Adolf Hitler, and improbable powerful organizations have been subject to crime fiction.[148] The Alps acted as a geographical barrier to Italy, and the Alps for centuries were permeated with established smuggling routes, known as green line. After World War II, members of the Schutzstaffel that feared prosecution as war criminals, known in modern English only as SS, disappeared into a crowd of refugees.[149] Massive numbers of refugees entered Italy illegally, by navigating the Alps.[150]

Undocumented migrants

[edit]Smugglers of humans claim that crossing the Alps is less dangerous, or deadly, than traveling 355 km on water between Tripoli and Lampedusa with a tramp ship (carretta del mare) or a dinghy. Undocumented migrants, visa overstayers, false tourists, asylum seekers, and other clandestine humans, lose their lives crossing the Alps. The exact number of smuggled humans who die a brutal death in the Alps can only be estimated.[151]

Largest Alpine cities

[edit]The largest city within the Alps is the city of Grenoble in France. Other larger and important cities within the Alps with over 100,000 inhabitants are in Tyrol with Bolzano/Bozen (Italy), Trento (Italy) and Innsbruck (Austria). Larger cities outside the Alps are Milan, Verona, Turin (Italy), Munich (Germany), Graz, Vienna, Salzburg (Austria), Ljubljana, Maribor, Kranj (Slovenia), Zürich, Geneva (Switzerland), Nice and Lyon (France).

Cities with over 100,000 inhabitants in the Alps are:

| Rank | Municipality | Inhabitants | Country | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 162,780 | France | ||

| 2 | 132,236 | Austria | ||

| 3 | 117,417 | Italy | ||

| 4 | 106,951 | Italy |

Alpine people and culture

[edit]The population of the region is 14 million spread across eight countries.[6] On the rim of the mountains, on the plateaus, and on the plains the economy consists of manufacturing and service jobs whereas in the higher altitudes and the mountains farming is still essential to the economy.[152] Farming and forestry continue to be mainstays of Alpine culture, industries that provide for export to the cities and maintain the mountain ecology.[153]

The Alpine regions are multicultural and linguistically diverse. Dialects are common and vary from valley to valley and region to region. In the Slavic Alps alone 19 dialects have been identified. Some of the Romance dialects spoken in the French, Swiss and Italian alps of Aosta Valley derive from Arpitan, while the southern part of the western range is related to Occitan; the German dialects derive from Germanic tribal languages.[154] Romansh, spoken by two percent of the population in southeast Switzerland, is an ancient Rhaeto-Romanic language derived from Latin, remnants of ancient Celtic languages and perhaps Etruscan.[154]

Much of the Alpine culture is unchanged since the medieval period when skills that guaranteed survival in the mountain valleys and the highest villages became mainstays, leading to strong traditions of carpentry, woodcarving, baking, pastry-making, and cheesemaking.[155]

Farming has been a traditional occupation for centuries, although it became less dominant in the 20th century with the advent of tourism. Grazing and pasture land are limited because of the steep and rocky topography of the Alps. In mid-June, cows are moved to the highest pastures close to the snowline, where they are watched by herdsmen who stay in the high altitudes often living in stone huts or wooden barns during the summers.[155] Villagers celebrate the day the cows are herded up to the pastures and again when they return in mid-September. The Almabtrieb, Alpabzug, Alpabfahrt, Désalpes ("coming down from the alps") is celebrated by decorating the cows with garlands and enormous cowbells while the farmers dress in traditional costumes.[155]

Cheesemaking is an ancient tradition in most Alpine countries. A wheel of cheese from the Emmental in Switzerland can weigh up to 45 kg (100 lb), and the Beaufort in Savoy can weigh up to 70 kg (150 lb). Owners of the cows traditionally receive from the cheesemakers a portion about the proportion of the cows' milk from the summer months in the high alps. Haymaking is an important farming activity in mountain villages that have become somewhat mechanized in recent years, although the slopes are so steep that scythes are usually necessary to cut the grass. Hay is normally brought in twice a year, often also on festival days.[155]

In the high villages, people live in homes built according to medieval designs that withstand cold winters. The kitchen is separated from the living area (called the stube, the area of the home heated by a stove), and second-floor bedrooms benefit from rising heat. The typical Swiss chalet originated in the Bernese Oberland. Chalets often face south or downhill and are built of solid wood, with a steeply gabled roof to allow accumulated snow to slide off easily. Stairs leading to upper levels are sometimes built on the outside, and balconies are sometimes enclosed.[155][156]

Food is passed from the kitchen to the stube, where the dining room table is placed. Some meals are communal, such as fondue, where a pot is set in the middle of the table for each person to dip into. Other meals are still served traditionally on carved wooden plates. Furniture has been traditionally elaborately carved and in many Alpine countries, carpentry skills are passed from generation to generation.

Roofs are traditionally constructed from Alpine rocks such as pieces of schist, gneiss, or slate.[157] Such chalets are typically found in the higher parts of the valleys, as in the Maurienne valley in Savoy, where the amount of snow during the cold months is important. The inclination of the roof cannot exceed 40%, allowing the snow to stay on top, thereby functioning as insulation from the cold.[158] In the lower areas where the forests are widespread, wooden tiles are traditionally used. Commonly made of Norway spruce, they are called "tavaillon".

In the German-speaking parts of the Alps (Austria, Bavaria, South Tyrol, Liechtenstein and Switzerland) and also Slovenia, there is a strong tradition of Alpine folk culture. Old traditions are carefully maintained among inhabitants of Alpine areas, even though this is seldom obvious to the visitor: many people are members of cultural associations where the Alpine folk culture is cultivated. At cultural events, traditional folk costume (in German Tracht) is expected: typically lederhosen for men and dirndls for women. Visitors can get a glimpse of the rich customs of the Alps at public Volksfeste. Even when large events feature only a little folk culture, all participants take part with gusto. Good opportunities to see local people celebrating the traditional culture occur at the many fairs, wine festivals, and firefighting festivals which fill weekends in the countryside from spring to autumn. Alpine festivals vary from country to country. Frequently they include music (e.g. the playing of Alpenhorns), dance (e.g. Schuhplattler), sports (e.g. wrestling marches and archery), as well as traditions with pagan roots such as the lighting of fires on Walpurgis Night and Saint John's Eve. Many areas celebrate Fastnacht in the weeks before Lent. Folk costume also continues to be worn for most weddings and festivals.[159][160]

Tourism

[edit]

The Alps are one of the more popular tourist destinations in the world with many resorts such as Oberstdorf, in Bavaria, Saalbach in Austria, Davos in Switzerland, Chamonix in France, and Cortina d'Ampezzo in Italy recording more than a million annual visitors. With over 120 million visitors a year, tourism is integral to the Alpine economy with much of it coming from winter sports, although summer visitors are also an important component.[161]

The tourism industry began in the early 19th century when foreigners visited the Alps, travelled to the bases of the mountains to enjoy the scenery, and stayed at the spa-resorts. Large hotels were built during the Belle Époque; cog-railways, built early in the 20th century, brought tourists to ever-higher elevations, with the Jungfraubahn terminating at the Jungfraujoch, well above the eternal snow-line, after going through a tunnel in Eiger. During this period winter sports were slowly introduced: in 1882 the first figure skating championship was held in St. Moritz, and downhill skiing became a popular sport with English visitors early in the 20th century,[161] as the first ski-lift was installed in 1908 above Grindelwald.[162]

In the first half of the 20th century the Olympic Winter Games were held three times in Alpine venues: the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France; the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland; and the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. During World War II the winter games were cancelled but after that time the Winter Games have been held in St. Moritz (1948), Cortina d'Ampezzo (1956), Innsbruck, Austria (1964 and 1976), Grenoble, France, (1968), Albertville, France, (1992), and Turin (2006).[163] In 1930, the Lauberhorn Rennen (Lauberhorn Race), was run for the first time on the Lauberhorn above Wengen;[164] the equally demanding Hahnenkamm was first run in the same year in Kitzbühl, Austria.[165] Both races continue to be held each January on successive weekends. The Lauberhorn is the more strenuous downhill race at 4.5 km (2.8 mi) and poses danger to racers who reach 130 km/h (81 mph) within seconds of leaving the start gate.[166]

During the post-World War I period, ski lifts were built in Swiss and Austrian towns to accommodate winter visitors, and summer tourism continued to be important. By the mid-20th century the popularity of downhill skiing increased greatly as it became more accessible and in the 1970s several new villages were built in France devoted almost exclusively to skiing, such as Les Menuires. Until this point, Austria and Switzerland had been the traditional and more popular destinations for winter sports, and by the end of the 20th century and into the early 21st century, France, Italy, and Tyrol began to see increases in winter visitors.[161] Since the 1980s tourism expansion and easy global access generate grave concerns regarding the loss of traditional Alpine culture and many uncertainties about sustainable development.[167] As a likely result of climatic change, the number of high altitude ski resorts and piste km is in decline since 2015, with snow-making machines installed at many sites.[168]

Avalanche/snow-slide

[edit]- 17th-century French-Italian border avalanche: in the 17th century about 2500 people were killed by an avalanche in a village on the French-Italian border.

- 19th century Zermatt avalanche: in the 19th century, 120 homes in a village near Zermatt were destroyed by an avalanche.[169]

- December 13, 1916 Marmolada-mountain-avalanche

- 1950–1951 winter-of-terror avalanches

- February 10, 1970 Val d'Isère avalanche

- February 9, 1999 Montroc avalanche

- February 21, 1999 Evolène avalanche

- February 23, 1999, Galtür avalanche, the deadliest avalanche in the Alps in 40 years

- July 2014 Mont-Blanc avalanche

- January 13, 2016 Les-Deux-Alpes avalanche

- January 18, 2016 Valfréjus avalanche

- July 3, 2022 Marmolada serac collapse

Transportation

[edit]

The region is serviced by 4,200 km (2,600 mi) of roads used by six million vehicles per year.[6] Train travel is well established in the Alps, with, for instance 120 km (75 mi) of track for every 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) in a country such as Switzerland.[170] Most of Europe's highest railways are located there. In 2007, the new 34.57 km-long (21.48 mi) Lötschberg Base Tunnel was opened, which circumvents the 100 years older Lötschberg Tunnel. With the opening of the 57.1 km-long (35.5 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel on June 1, 2016, it bypasses the Gotthard Tunnel built in the 19th century and realizes the first flat route through the Alps.[171]

Some high mountain villages are car-free either because of inaccessibility or by choice. Wengen, and Zermatt (in Switzerland) are accessible only by cable car or cog-rail trains. Avoriaz (in France), is car-free, with other Alpine villages considering becoming car-free zones or limiting the number of cars for reasons of sustainability of the fragile Alpine terrain.[172]

The lower regions and larger towns of the Alps are well-served by motorways and main roads, but higher mountain passes and byroads, which are amongst the highest in Europe, can be treacherous even in summer due to steep slopes. Many passes are closed in winter. Several airports around the Alps (and some within), as well as long-distance rail links from all neighbouring countries, afford large numbers of travellers easy access.[6]

Notes

[edit]- ^ French: Alpes [alp]; German: Alpen [ˈalpn̩] ; Italian: Alpi [ˈalpi]; Romansh: Alps [alps]; Slovene: Alpe [ˈáːlpɛ].

- ^ The Caucasus Mountains are higher, and the Urals longer.

- ^ Depending on the definitions used, a small mountain range in western Hungary may also qualify as part of the Alps, although these are more typically classified as foothills, and Hungary is not considered to be an Alpine country.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "Le Mont-Blanc passe de 4.810 mètres à 4.808,7 mètres". bfmtv.com (in French). Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ "Alps". The Hutchinson unabridged encyclopedia with atlas and weather guide. Abington, United Kingdom: Helicon. 2014. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ kutka, petr (February 21, 2022). "Víte, že jsou Alpy i v Maďarsku? Geografická zajímavost a tip na příjemný výlet". Světoběžník.info (in Czech). Archived from the original on December 20, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ "The Alpine Convention". Alpine Convention. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

The Alps are a fascinating and spectacular mountain range spanning eight countries: Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Slovenia, and Switzerland.

- ^ "Ötzi the Iceman". www.iceman.it. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Chatré, Baptiste, et al. (2010), 8

- ^ a b "Alp | Origin and meaning of alp by Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Jennifer Nimmo (2004). The river Alpheus in Greek, Christian and Byzantine thought. Byzantion

- ^ Maurus Servius Honoratus. "Book 10, line 13". In Georgius Thilo (ed.). Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii carmina commentarii (in Latin). Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. May 14, 1955. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c Schmid, Stefan M.; Genschuh, Bernhard; Kissling, Eduard; Schuster, Ralf (2004). "Tectonic map and overall architecture of the Alpine orogen". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 97 (1): 93. Bibcode:2004SwJG...97...93S. doi:10.1007/s00015-004-1113-x. S2CID 22393862.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reynolds, (2012), 43–45

- ^ a b Fleming (2000), 4

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 117–19

- ^ a b c Ceben (1998), 22–24

- ^ a b c Chatré, Baptiste, et al. (2010), 9

- ^ Fleming (2000), 1

- ^ a b c Beattie (2006), xii–xiii

- ^ "Alpine Convention - the Convention - the Alpine Convention in a nutshell - the Alps - Home". Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ Shoumtoff (2001), 23

- ^ Excluding the Piz Zupò and Piz Roseg located in the Bernina range, close to Piz Bernina.

- ^ "Alps | Definition, Map, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Die Alpen: Hydrologie und Verkehrsübergänge (German)". Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Coolidge, Lake & Knox 1911, p. 740.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopedia Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica; retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "History of the Great St Bernard pass". Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Thiers, Frédéric (August 10, 2016). "Ronce, le gardien silencieux du col du Mont-Cenis". Le Dauphiné libéré. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Kalla-Bishop, P. M. (1971). Italian Railways. Newton Abbott, Devon, England: David & Charles. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-7153-5168-0.

- ^ Swiss National Map

- ^ "Wer hat die grösste Röhre?" [Who has the longest tube?]. Tages-Anzeiger (graphical animation) (in German). Zürich. April 14, 2016. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "Was die Tunnelbauer im Gotthard antrafen". Tages-Anzeiger (graphical animation) (in German). Zürich. April 1, 2016. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "Official Timetable" (in English, German, French, Italian, and Romansh). Bern: Swiss Federal Office for Transport. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "The 4000ers of the Alps: Official UIAA List" (PDF). UIAA-Bulletin (145). March 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2010.

- ^ Michael Huxley, The Geographical magazine: Volume 59, Geographical Press, 1987

- ^ a b Shoumatoff (2001), 197–200

- ^ "4000 m Peaks of the Alps". Bielefeldt.de. July 6, 2010. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c Graciansky (2011), 1–2

- ^ a b c Graciansky (2011), 5

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 35

- ^ a b Gerrard, (1990), 9

- ^ a b c Gerrard, (1990), 16

- ^ Earth (2008), 142

- ^ a b Schmid (2004), 102

- ^ a b c d Schmid (2004), 97

- ^ a b Schmid, 99

- ^ Schmid (2004), 103

- ^ Graciansky (2011), 29

- ^ Graciansky (2011), 31

- ^ Beattie (2006), 6–8

- ^ "SED | Earthquakes and the Alps". Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "The largest earthquakes in the Alps". Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Sternai, Pietro; Sue, Christian; Husson, Laurent; Serpelloni, Enrico; Becker, Thorsten W.; Willett, Sean D.; Faccenna, Claudio; Di Giulio, Andrea; Spada, Giorgio; Jolivet, Laurent; Valla, Pierre; Petit, Carole; Nocquet, Jean-Mathieu; Walpersdorf, Andrea; Castelltort, Sébastien (March 2019). "Present-day uplift of the European Alps: Evaluating mechanisms and models of their relative contributions". Earth-Science Reviews. 190: 589–604. Bibcode:2019ESRv..190..589S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.01.005. hdl:10281/229017. ISSN 0012-8252. S2CID 96447591.

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 49–53

- ^ Roth, 10–17

- ^ a b c d e Shoumatoff (2001), 63–68

- ^ Gerrard, (1990), 132

- ^ a b Shoumatoff (2001), 71–72

- ^ Gerrard, (1990), 78

- ^ Gerrard, (1990), 108

- ^ Ceben (1998), 38

- ^ Sternai, P.; Herman, F.; Fox, M. R.; Castelltort, S. (July 13, 2011). "Hypsometric analysis to identify spatially variable glacial erosion". Journal of Geophysical Research. 116 (F3): F03001. Bibcode:2011JGRF..116.3001S. doi:10.1029/2010JF001823. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ^ Sternai, Pietro; Herman, Frédéric; Valla, Pierre G.; Champagnac, Jean-Daniel (April 15, 2013). "Spatial and temporal variations of glacial erosion in the Rhône valley (Swiss Alps): Insights from numerical modeling" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 368: 119–131. Bibcode:2013E&PSL.368..119S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.02.039. ISSN 0012-821X. S2CID 14687787.

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 31

- ^ Chatré, Baptiste, et al. (2010), 5

- ^ a b Benniston et al. (2011), 1

- ^ Price, Martin. Mountains: Globally Important Eco-systems. University of Oxford

- ^ Alpine Convention (2010), 8

- ^ a b Benniston et al. (2011), 3

- ^ a b Ceben (1998), 31

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 24, 31

- ^ "Lake Garda". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Chatré, Baptiste, et al. (2010), 13

- ^ Coolidge, Lake & Knox 1911, p. 737.

- ^ Fleming (2000), 3

- ^ Ceben (1998), 34–36

- ^ Viazzo (1980), 17

- ^ a b Carrer, Marco; Dibona, Raffaella; Prendin, Angela Luisa; Brunetti, Michele (February 2023). "Recent waning snowpack in the Alps is unprecedented in the last six centuries". Nature Climate Change. 13 (2): 155–160. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13..155C. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01575-3. hdl:11577/3477269. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ Benniston (2011), 3–4

- ^ "IPCC regional fact sheet - Mountains" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Huss, Matthias; Hock, Regine; Bauder, Andreas; Funk, Martin (May 1, 2010). "100-year mass changes in the Swiss Alps linked to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (10): L10501. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3710501H. doi:10.1029/2010GL042616. ISSN 1944-8007. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Zampieri, Matteo; Scoccimarro, Enrico; Gualdi, Silvio (January 1, 2013). "Atlantic influence on spring snowfall over the Alps in the past 150 years". Environmental Research Letters. 8 (3): 034026. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8c4026Z. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034026. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Zampieri, Matteo; Scoccimarro, Enrico; Gualdi, Silvio; Navarra, Antonio (January 15, 2015). "Observed shift towards earlier spring discharge in the main Alpine rivers". Science of the Total Environment. Towards a better understanding of the links between stressors, hazard assessment and ecosystem services under water scarcity. 503–504: 222–232. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.503..222Z. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.036. hdl:2122/9055. PMID 25005239.

- ^ Coolidge, Lake & Knox 1911, p. 738.

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 75

- ^ Beattie (2006), 17

- ^ Körner (2003), 9

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 85

- ^ qtd in Beattie (2006), 17

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 87

- ^ a b Sharp (2002), 14

- ^ Kala, C.P. and Ratajc, P. 2012."High altitude biodiversity of the Alps and the Himalayas: ethnobotany, plant distribution and conservation perspective". Archived October 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Biodiversity and Conservation, 21 (4): 1115–1126.

- ^ Gerrard (1990), 225

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 90, 96, 101

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 104

- ^ Rupicapra rupicapra [Linnaeus, 1758] [1] Archived April 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 101

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 102–103

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 97–98

- ^ a b Shoumatoff (2001), 96

- ^ a b Shoumatoff (2001), 88–89

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 93

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 91

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 75

- ^ a b Beattie, (2006), 25

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 21

- ^ "Luca Ermini et al., "Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of the Tyrolean Iceman," Current Biology, vol. 18, no. 21 (30 October 2008), pp. 1687–1693". Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 31, 34

- ^ Fleming (2000), 2

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 131

- ^ Karim Mata (2019). Iron Age Slaving and Enslavement in Northwest Europe. Archaeopress Publishing Limited. p. 18. ISBN 9781789694192.

- ^ Lancel, Serge, (1999), 71

- ^ Prevas (2001), 68–69

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 27

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 28–31

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 32, 34, 37, 43

- ^ Mershman, Francis. "St. Maurice", The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 10. New York City: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 6 March 2013

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 41, 46, 48

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 73, 75–76

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 56, 66

- ^ Jon Mathieu (2019). The Alps: An Environmental History. Polity Press. ISBN 9781509527748.

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 182–183

- ^ Alexander Statiev (2018). At War's Summit. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 9781108684170.

- ^ Cornelis van der Haven; Erika Kuijpers, eds. (2016). Battlefield Emotions 1500-1800: Practices, Experience, Imagination. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 96. ISBN 9781137564900.

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 69-70

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 108

- ^ Coolidge, Lake & Knox 1911, p. 748.

- ^ a b Shoumatoff (2001), 188–191

- ^ Fleming (2000), 6

- ^ Fleming (2000), 12

- ^ Fleming (2000), 5

- ^ qtd in Shoumatoff (2001), 193

- ^ Shoumatoff (2001), 192–194

- ^ Fleming (2000), 8

- ^ a b Fleming (2000), vii

- ^ Fleming (2000), 27

- ^ Fleming (2000), 12–13, 30, 27

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 121–123

- ^ Goethe en Suisse et dans les Alpes: Voyages de 1775, 1779 et 1797

- ^ a b Fleming (2000), 83

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 125–126

- ^ Geoffrey Hartman, "Gods, Ghosts, and Shelley's 'Atheos'", Literature and Theology, Volume 24, Issue 1, pp. 4–18

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 127–133

- ^ Beattie, (2006), 139

- ^ Fleming, Fergus (November 3, 2000). "Cliffhanger at the top of the world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Gilles Modica "1865: the Golden Age of Mountaineering" (2016), pp 10.

- ^ "Die Besteigung der Berge - Die Dolomitgipfel werden erobert (German: The ascent of the mountains - the dolomite peaks are conquered)". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Despina Stratigakos (2015). Hitler at Home. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300187601.

- ^ Gerald Steinacher (2011). Nazis on the Run: How Hitler's Henchmen Fled Justice. OUP Oxford. p. xvi. ISBN 9780191653766.

- ^ Gerald Steinacher (2011). Nazis on the Run: How Hitler's Henchmen Fled Justice. OUP Oxford. p. 3. ISBN 9780191653766.

- ^ Gerald Steinacher (2011). Nazis on the Run: How Hitler's Henchmen Fled Justice. OUP Oxford. p. 15. ISBN 9780191653766.

- ^ Francesca Fauri, ed. (2014). The History of Migration in Europe: Perspectives from Economics, Politics and Sociology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317678281.

- ^ Chartes et. el. (2010), 14

- ^ Chartes et. el. (2010), 5

- ^ a b Shoumataff (2001), 114–166

- ^ a b c d e Shoumataff (2001), 123–126

- ^ Shoumataff (2001), 134

- ^ Shoumataff (2001), 131, 134

- ^ "Cahier d'architecture Haute Maurienne/Vanoise" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ^ Shoumataff (2001), 129, 135

- ^ Anita Ericson, Österreich [Marco Polo travel guide], 13th edition, Marco Polo, Ostfildern (Germany), 2017, Pp. 21f.

- ^ a b c Bartaletti, Fabrizio."What Role Do the Alps Play within World Tourism?" Archived April 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Commission Internationale pour la Protection des Alpes. CIRPA.org. Retrieved August 9, 2012

- ^ Beattie (2006), 198

- ^ "21 Past Olympic Games" Archived October 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Olympic.org. Retrieved August 13, 2012

- ^ Lauberhorn History Archived August 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Hahenkamm Races Kitzbuhel" Archived February 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. HKR.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012,

- ^ Lauberhorn Downhill Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Briand, F.; Dubost, M.; Pitt, D.; Rambaud, D. (1989). The Alps - A system under pressure. IUCN. p. 128. ISBN 2-88032-983-3.

- ^ "Ski resorts of the Alps: the development, 'Marmota Maps'". November 15, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Fleming (2000), 89–90

- ^ "Rail". Archived May 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Swissworld.org. Retrieved August 20, 2012,

- ^ "Welcome to the AlpTransit Portal". Bern: Swiss Federal Archives SFA. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ Hudson (2000), 107

Works cited

[edit]- Alpine Convention. (2010). The Alps: People and pressures in the mountains, the facts at a glance Archived November 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Allaby, Michael et al. The Encyclopedia of Earth. (2008). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25471-8

- Beattie, Andrew. (2006). The Alps: A Cultural History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530955-3

- Benniston, Martin, et al. (2011). "Impact of Climatic Change on Water and Natural Hazards in the Alps". Environmental Science and Policy. Volume 30. 1–9

- Cebon, Peter, et al. (1998). Views from the Alps: Regional Perspectives on Climate Change. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03252-0

- Chatré, Baptiste, et al. (2010). The Alps: People and Pressures in the Mountains, the Facts at a Glance. Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention (alpconv.org). Retrieved August 4, 2012. ISBN 978-88-905158-2-8

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort; Lake, Philip; Knox, Howard Vincent (1911). "Alps". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). pp. 737–754.

- De Graciansky, Pierre-Charles et al. (2011). The Western Alps, From Rift to Passive Margin to Orogenic Belt. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53724-9

- Feuer, A.B. (2006). Packs On!: Memoirs of the 10th Mountain Division in World War II. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3289-5

- Fleming, Fergus. (2000). Killing Dragons: The Conquest of the Alps. New York: Grove. ISBN 978-0-8021-3867-5

- Gerrard, AJ. (1990) Mountain Environments: An Examination of the Physical Geography of Mountains. Boston: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-07128-4

- Halbrook, Stephen P. (1998). Target Switzerland: Swiss Armed Neutrality in World War II. Rockville Center, NY: Sarpedon. ISBN 978-1-885119-53-7

- Halbrook, Stephen P. (2006). The Swiss and the Nazis: How the Alpine Republic Survived in the Shadow of the Third Reich. Havertown, PA: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932033-42-7

- Hudson, Simon. (2000). Snow Business: A Study of the International Ski Industry. New York: Cengage ISBN 978-0-304-70471-2

- Körner, Christian. (2003). Alpine Plant Life. New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-00347-2

- Lancel, Serge. (1999). Hannibal. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21848-7

- Mitchell, Arthur H. (2007). Hitler's Mountain. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2458-0

- Prevas, John. (2001). Hannibal Crosses The Alps: The Invasion Of Italy And The Punic Wars. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81070-1

- Reynolds, Kev. (2012) The Swiss Alps. Cicerone Press. ISBN 978-1-85284-465-3

- Roth, Philipe. (2007). Minerals first Discovered in Switzerland. Lausanne, CH: Museum of Geology. ISBN 978-3-9807561-8-1