Cuban Revolution

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

| Cuban Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fidel Castro and his men in the Sierra Maestra, 1956 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,000 killed[1] Arms captured:

| 1,000 killed[1] | ||||||

| Thousands of civilians tortured and murdered by Batista's government; unknown number of people executed by the Rebel Army[3][4][5][6] | |||||||

| History of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

|

|

| Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

|

|

| Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

|

| US Military Government (1898–1902) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Cuban Revolution (Spanish: Revolución cubana) was the military and political overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's dictatorship, which had reigned as the government of Cuba between 1952 and 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, which saw Batista topple the nascent Cuban democracy and consolidate power. Among those opposing the coup was Fidel Castro, then a novice attorney who attempted to contest the coup through Cuba's judiciary. Once these efforts proved fruitless, Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl led an armed attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks on 26 July 1953.

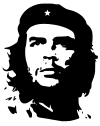

Following the attack's failure, Fidel Castro and his co-conspirators were arrested and formed the 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) in detention. At his trial, Fidel Castro launched into a two hour speech that won him national fame as he laid out his grievances against the Batista dictatorship. In an attempt to win public approval, Batista granted amnesty to the surviving Moncada Barracks attackers and the Castros fled into exile. During their exile, the Castros consolidated their strategy in Mexico and subsequently reentered Cuba in 1956, accompanied by Che Guevara, whom they had encountered during their time in Mexico.

Returning to Cuba aboard the Granma, the Castros, Guevara, and other supporters encountered gunfire from Batista's troops. The rebels fled to the Sierra Maestra where the M-26-7 rebel forces would reorganize, conducting urban sabotage and covert recruitment. Over time the Popular Socialist Party, once the largest and most powerful organizations opposing Batista, would see its influence and power wane in favor of the 26th of July Movement. As the irregular war against Batista escalated, the rebel forces transformed from crude, guerrilla fighters into a cohesive fighting force that could confront Batista's army in military engagements. By the time the rebels were able to oust Batista, the revolution was being driven by a coalition between the Popular Socialist Party, the 26th of July Movement and the Revolutionary Directorate of 13 March.[7]

The rebels, led by the 26th of July Movement, finally toppled Batista on 31 December 1958, after which he fled the country. Batista's government was dismantled as Castro became the most prominent leader of the revolutionary forces. Soon thereafter, the 26th of July Movement established itself as the de facto government. Although Castro was immensely popular in the period immediately following Batista's ouster, he quickly consolidated power, leading to domestic and international tensions. 26 July 1953 is celebrated in Cuba as Día de la Revolución (from Spanish: "Day of the Revolution"). The 26th of July Movement later reformed along Marxist–Leninist lines, becoming the Communist Party of Cuba in October 1965.[8]

The Cuban Revolution had powerful and profound domestic and international repercussions. In particular, it shipwrecked Cuba–United States relations, although efforts to improve them, such as the Cuban thaw, gained momentum during the 2010s and have continued through the 2020s.[9][10] In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Castro's government began a program of nationalization, centralization of the press and political consolidation that transformed Cuba's economy and civil society, angering sectors of the Cuban population and the American government.[11] In the aftermath of the revolution, Castro's authoritarianism in conjunction with the struggling economy lead to the Cuban Exodus as citizens fled the island, with the majority arriving in the United States.[12] The revolution also heralded an era of Cuban intervention in foreign conflicts in Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia,[13] and the Middle East, beginning on 24 April 1959 when Cuba tried and failed to invade Panama.[14][15] Several rebellions occurred between 1959 and 1965, mainly in the Escambray Mountains, which were suppressed by the revolutionary government.[16]

Background

[edit]Corruption in Cuba

[edit]

The Republic of Cuba at the turn of the 20th century was largely characterized by a deeply ingrained tradition of corruption where political participation resulted in opportunities for elites to engage in wealth accumulation.[17] Cuba's first presidential period under Don Tomás Estrada Palma from 1902 to 1906 was considered to uphold the best standards of administrative integrity in the history of the Republic of Cuba.[18][page needed] However, a United States intervention in 1906 resulted in Charles Edward Magoon, an American diplomat, taking over the government until 1909. Although Magoon's government did not condone corrupt practices, there is debate as to how much was done to stop what was widespread especially with the surge of American money coming into the small country. Hugh Thomas suggests that while Magoon disapproved of corrupt practices, corruption still persisted under his administration and he undermined the autonomy of the judiciary and their court decisions.[19][a] On 29 January 1909, the sovereign government of Cuba was restored, and José Miguel Gómez became president. No explicit evidence of Magoon's corruption ever surfaced, but his parting gesture of issuing lucrative Cuban contracts to U.S. firms was a continued point of contention. Cuba's subsequent president, José Miguel Gómez, was the first to become involved in pervasive corruption and government corruption scandals. These scandals involved bribes that were allegedly paid to Cuban officials and legislators under a contract to search the Havana harbour, as well as the payment of fees to government associates and high-level officials.[18][page needed] Gómez's successor, Mario García Menocal, wanted to put an end to the corruption scandals and claimed to be committed to administrative integrity as he ran on a slogan of "honesty, peace and work".[18][page needed] Despite his intentions, corruption actually intensified under his government from 1913 to 1921.[20][b] Instances of fraud became more common while private actors and contractors frequently colluded with public officials and legislators. Charles Edward Chapman attributes the increase of corruption to the sugar boom that occurred in Cuba under the Menocal administration.[21] Furthermore, the advent of World War One enabled the Cuban government to manipulate sugar prices, the sales of exports and import permits.[18][page needed] While in office, García Menocal hosted his college fraternity, in the 1920 Delta Kappa Epsilon National Convention, the first international fraternity conference outside the US, which took place in Cuba. He was responsible for creating the Cuban Peso; until his presidency Cuba used both the Spanish Real and US Dollar. President Menocal left the Cuban national treasury in overdraft and therefore in precarious financial situation. Menocal supposedly spent $800 million during his 8 years in office and left a floating debt of $40 million.[citation needed]

Alfredo Zayas succeeded Menocal from 1921 to 1925 and engaged in what Calixto Masó refers to as the "maximum expression of administrative corruption".[18][page needed] Both petty and grand corruption spread to nearly all aspects of public life and the Cuban administration became largely characterized by nepotism as Zayas relied on friends and relatives to illegally gain greater access to wealth.[22][c] Gerardo Machado succeeded Zayas from 1925 to 1933, and entered the presidency with widespread popularity and support from the major political parties. However, his support declined over time. Due to Zayas' previous policies, Gerardo Machado aimed to diminish corruption and improve the public sector's performance through an "honest administration", which had been referred to as moralización,[23] from 1925 to 1933. While he was successfully able to reduce the amounts of low level and petty corruption, grand corruption still largely persisted.[24] Machado embarked on development projects that enabled the persistence of grand corruption through inflated costs and the creation of "large margins" that enabled public officials to appropriate money illegally.[25] Under his government, opportunities for corruption became concentrated into fewer hands with "centralized government purchasing procedures" and the collection of bribes among a smaller number of bureaucrats and administrators.[26] Through the development of real estate infrastructures and the growth of Cuba's tourism industry, Machado's administration was able to use insider information to profit from private sector business deals.[citation needed] Many people objected to his running again for re-election in 1928, as his victory violated his promise to serve for only one term. As protests and rebellions became more strident, his administration curtailed free speech and used repressive police tactics against opponents. Machado unleashed a wave of violence against his critics, and there were numerous murders and assassinations committed by the police and army under Machado's administration.[23] The extent of his involvement in these is disputed, though Russell Porter makes the claim that Machado confessed to being involved.[25] Though the extent of Machado's participation in such violent acts is unknown, he has since been described as a dictator. In May 1933, Machado was forced out as newly appointed US ambassador Sumner Welles arrived in Cuba and initiated negotiation with the opposition groups for a government to succeed Machado's.[27] A provisional government headed by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada (son of Cuban independence hero Carlos Manuel de Céspedes) and including members of the ABC was brokered; it took power on 12 August 1933[28] amidst a general strike in Havana.[27]

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada subsequently was offered the position of President by ambassador Sumner Welles. He took office on 12 August 1933, and Welles proposed that "general elections may be held approximately 3 months from now so that Cuba may once more have a constitutional government in the real sense of the word." Céspedes agreed, and declared that a general election would be held on 24 February 1934, for a new presidential term to begin on 20 May 1934. However, on 4-5 September 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt took place while Céspedes was in Matanzas and Santa Clara after a hurricane had ravaged those regions. The junta of officers led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista and students proclaimed that it had taken power in order to fulfill the aims of the revolution; it briefly described a program which included economic restructuring, punishment of wrongdoers, recognition of public debts, creation of courts, political reorganization, and any other actions necessary to construct a new Cuba based on justice and democracy.[29] Only five days after the coup, Batista and the Student Directory promoted Ramón Grau to the role of President. The ensuing One Hundred Days Government issued a number of reformist declarations but never gained diplomatic recognition from the US; it was overthrown in January 1934 under pressure from Batista and the US ambassador. Grau was replaced by Carlos Mendieta, and within five days the U.S. recognized Cuba's new government. The corruption was not curtailed under Mendieta and he resigned in 1935 after unrest continued, and their followed a number of interim and weak presidents under the guidance of Batista and the US. Batista, supported by the Democratic Socialist Coalition which included Julio Antonio Mella's Communist Party, defeated Grau in the first presidential election under the new Cuban constitution in the 1940 election, and served a four-year term as President of Cuba. Batista was endorsed by the original Communist Party of Cuba (later known as the Popular Socialist Party), which at the time had little significance and no probability of an electoral victory. This support was primarily due to Batista's labor laws and his support for labor unions, with which the Communists had close ties. In fact, Communists attacked the anti-Batista opposition, saying Grau and others were "fascists" and "reactionaries".

Senator Eduardo Chibás dedicated himself to exposing corruption in the Cuban government, and formed the Partido Ortodoxo in 1947 to further this aim. Argote-Freyre points out that Cuba's population under the Republic had a high tolerance for corruption. Furthermore, Cubans knew and criticized who was corrupt, but admired them for their ability to act as "criminals with impunity".[30][page needed] Corrupt officials went beyond members of congress to also include military officials who granted favours to residents and accepted bribes.[30][page needed] The establishment of an illegal gambling network within the military enabled army personnel such as Lieutenant Colonel Pedraza and Major Mariné to engage in extensive illegal gambling activities.[30][page needed] Mauricio Augusto Font and Alfonso Quiroz, authors of The Cuban Republic and José Martí, say that corruption "pervaded in political life" under the administrations of Presidents Ramón Grau and Carlos Prío Socarrás.[31] Prío was reported to have stolen over $90 million in public funds, which was equivalent to one fourth of the annual national budget.[32] Prior to the Communist revolution, Cuba was ruled under the elected government of Fulgencio Batista from 1940 to 1944. Throughout this time period, Batista's support base consisted mainly of corrupt politicians and military officials. Batista himself was able to heavily profit from the regime before coming into power through inflated government contracts and gambling proceeds.[30][page needed] In 1942, the British Foreign Office reported that the U.S. State Department was "very worried" about corruption under President Fulgencio Batista, describing the problem as "endemic" and exceeding "anything which had gone on previously". British diplomats believed that corruption was rooted within Cuba's most powerful institutions, with the highest individuals in government and military being heavily involved in gambling and the drug trade.[33] In terms of civil society, Eduardo Saenz Rovner writes that corruption within the police and government enabled the expansion of criminal organizations in Cuba.[34] Batista refused U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt's offer to send experts to help reform the Cuban Civil Service.[citation needed] Batista didn't run in the 1944 election, and Partido Auténtico party member Ramón Grau was elected president,[35] and oversaw extensive corruption during his administration. He had Carlos Prío Socarrás serve turns as Minister of Public Works, Minister of Labor and Prime Minister.[36] On the next election 1 July 1948, Prio was elected president of Cuba as a member of the Partido Auténtico which presided over corruption and irresponsible government of this period.[37] Prío was assisted by Chief of the Armed Forces General Genobebo Pérez Dámera and Colonel José Luis Chinea Cardenas, who had previously been in charge of the Province of Santa Clara.

The eight years under Grau and Prío, were marked by violence among political factions and reports of theft and self-enrichment in the government ranks.[38] The Prío administration increasingly came to be perceived by the public as ineffectual in the face of violence and corruption, much as the Grau administration before it.

With elections scheduled for the middle of 1952, rumors surfaced of a planned military coup by long-shot presidential contender Fulgencio Batista. Prío, seeing no constitutional basis to act, did not do so. The rumors proved to be true. On 10 March 1952, Batista and his collaborators seized military and police commands throughout the country and occupied major radio and TV stations. Batista assumed power when Prío, failing to mount a resistance, boarded a plane and went into exile.

Batista, after his military coup against Prío Socarras, again took power and ruled until 1959. Under his rule, Batista led a corrupt dictatorship that involved close links with organized crime organizations and the reduction of civil freedoms of Cubans. This period resulted in Batista engaging in more "sophisticated practices of corruption" at both the administrative and civil society levels. Batista and his administration engaged in profiteering from the lottery as well as illegal gambling.[39] Corruption further flourished in civil society through increasing amounts of police corruption, censorship of the press as well as media, and creating anti-communist campaigns that suppressed opposition with violence, torture and public executions.[40] The former culture of toleration and acceptance towards corruption also dissolved with the dictatorship of Batista. For instance, a Cuban student stated, "however corrupt Grau and Prío were, we elected them and therefore allowed them to steal from us. Batista robs us without our permission."[41] Corruption under Batista further expanded into the economic sector with alliances that he forged with foreign investors and the prevalence of illegal casinos and criminal organizations in the country's capital of Havana.[42]

Batista regime

[edit]In the decades following the United States' invasion of Cuba in 1898, and formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, Cuba experienced a period of significant instability, enduring a number of revolts, coups and a period of U.S. military occupation. Batista became president for the second time in 1952, after seizing power in a military coup and canceling the 1952 elections.[43] Although Batista had been relatively progressive during his first term, in the 1950s he proved far more dictatorial and indifferent to popular concerns.[44][45] While Cuba remained plagued by high unemployment and limited water infrastructure,[46] Batista antagonized the population by forming lucrative links to organized crime[47][48] and allowing American companies to dominate the Cuban economy, especially sugar-cane plantations and other local resources.[46] Although the US armed and politically supported the Batista dictatorship, later US president John F. Kennedy recognized its corruption and the justifiability of removing it.[49]

During his first term as president, Batista was supported by the original Communist Party of Cuba (later known as the Popular Socialist Party),[50] but during his second term he became strongly anti-communist.[51] In the months following the March 10, 1952 coup d'etat, Fidel Castro, then a young lawyer and activist, put into motion a lawsuit against Batista, whom he accused of corruption and tyranny. However, Castro's constitutional arguments were rejected by the Cuban courts, as the coup was perceived as being a "de facto, revolutionary overturn of the constitution".[52][d] After deciding that the Cuban regime could not be replaced through legal means, Castro resolved to launch an armed revolution. To this end, he and his brother Raúl founded a paramilitary organization known as "The Movement", stockpiling weapons and recruiting around 1,200 followers from Havana's disgruntled working class by the end of 1952.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Early stages: 1953–1955

[edit]Attack on the Moncada Barracks

[edit]

Striking their first blow against the Batista government, Fidel and Raúl Castro gathered an upwards of 126 fighters[53][e] and planned a multi-pronged attack on several military installations. On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago and the barracks in Bayamo[54] only to be decisively defeated by the far more numerous government soldiers following a call to withdraw when Fidel Castro realized a lack of adequate knowledge about the barracks, as well as the lack of weapon experience amongst the recruited fighters, would ultimately lead to failure.[55] It was hoped that the staged attack would spark a nationwide revolt against Batista's government. After an hour of fighting most of the rebels and their leader fled to the mountains.[56] The exact number of rebels killed is debatable; however, in his autobiography, Fidel Castro claimed that five were killed in the midst of battle, and an additional fifty-six were executed after being captured by the Batista government.[57] Due to the government's large number of men, Hunt revised the number to be around 60 members taking the opportunity to flee to the mountains along with Castro.[56] Among the dead was Abel Santamaría, Castro's second-in-command, who was imprisoned, tortured, and executed on the same day as the attack.[58]

Imprisonment and immigration

[edit]Numerous key Movement revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured shortly afterwards. In a highly political trial, Fidel spoke for nearly four hours in his defense, ending with the words "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me." Castro's defense was based on nationalism, the representation and beneficial programs for the non-elite Cubans, and his patriotism and justice for the Cuban community.[59] In October 1953, Fidel was sentenced to fifteen years in the Presidio Modelo prison, located on Isla de Pinos,[60] while Raúl was sentenced to thirteen years.[61] However, in 15 May 1955, under broad political pressure, the Batista government freed all political prisoners in Cuba, including the Moncada attackers. Fidel's Jesuit childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release.[62]

Soon, the Castro brothers joined with other exiles in Mexico to prepare for the overthrow of Batista, receiving training from Alberto Bayo, a leader of Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. On 12 June 1955, the revolutionaries named themselves the "26th of July Movement", in reference to the date of their attack on the Moncada Barracks in 1953. A month later, in July, Fidel met the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara in Mexico, the latter joining his cause.[62] Raúl and Fidel's chief advisor Ernesto aided the initiation of Batista's amnesty.[59]

Student demonstrations

[edit]By late 1955, student riots and demonstrations became more common, and unemployment became problematic as new graduates could not find jobs.[63][64][f] These protests were dealt with increasing repression. All young people were seen as possible revolutionaries.[65] Due to its continued opposition to the Cuban government and much protest activity taking place on its campus, the University of Havana was temporarily closed on 30 November 1956 (it did not reopen until 1959 under the first revolutionary government).[66]

Attack on the Domingo Goicuria Barracks

[edit]While the Castro brothers and the other 26 July Movement guerrillas were training in Mexico and preparing for their amphibious deployment to Cuba, another revolutionary group followed the example of the Moncada Barracks assault. On 29 April 1956, an Auténtico guerrilla group comprised of an upwards of thirty rebels[g], brought together by Reynold García, attacked the Domingo Goicuría Barracks in the Matanzas province.[67][68] A total of fifteen rebels died, with five killed during battle and the remaining ten captured and executed. At least one rebel had been executed by Pilar García, Batista's garrison commander.[69] Florida International University historian Miguel A. Bretos was in the nearby cathedral when the firefight began. In his 2011 biography, titled Matanzas: The Cuba Nobody Knows', he wrote: "That day the Cuban Revolution began for me and Matanzas."[70]

Insurgency: 1956–1957

[edit]

Granma landing

[edit]The yacht Granma departed from Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico, on 25 November 1956, carrying the Castro brothers and eighty others, even though the yacht was designed to accommodate twelve people with a maximum of twenty-five. The yacht landed in Playa Las Coloradas on 2 December, in the southern municipality of Niquero,[71] arriving two days later than planned because the boat was heavily loaded, unlike during the practice sailing runs.[72] This dashed any hopes for a coordinated attack with the llano wing of the Movement.[73] After arriving and exiting the ship, the band of rebels began to make their way into the Sierra Maestra mountains, a range in southeastern Cuba. Three days after the trek began, Batista's army attacked and killed most of the Granma participants – while the exact number is disputed, no more than twenty of the original eighty-two men survived the initial encounters with the Cuban army and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.[74]

The group of survivors included Fidel and Raúl Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. The dispersed survivors, alone or in small groups, wandered through the mountains, looking for each other. Eventually, the men would link up again – with the help of peasant sympathizers – and would form the core leadership of the guerrilla army. A number of female revolutionaries, including Celia Sánchez and Haydée Santamaría (the sister of Abel Santamaría), also assisted Fidel Castro's operations in the mountains.[75][76]

The Battle of La Plata

[edit]On 17 January 1957, the 26th of July Movement engaged in armed combat with Cuba's small army garrison stationed in barracks in La Plata, a village in the Sierra Maestra mountain. The battle began at 2:40 am, initiated by Fidel who shot the first two bullets.[77] There had been a brief moment of urgency on the rebels' end, as the army garrison had been pushing forward in an unexpectedly relentless manner, whilst the rebels' explosives were not detonating when thrown. Subsequently, Guevara and Luis Crespo closed in on the barracks and the latter set it on fire, helping ward off the soldiers and shoot those who were in the line of fire. It was not long before the Cuban army garrison surrendered. In the end, the rebels were uninjured. In contrast, two Cuban soldiers died in the midst of battle, five were wounded, and three were taken as prisoners (they ultimately succumbed to their injuries); only some were able to escape. Only one of the surviving Cuban army soldiers worked under the command of Raúl following the battle, eventually being promoted to lieutenant.[78]

The 26th of July Movement's success in this battle marked the first major victory the rebels.[79] In addition, the men took advantage of the available loot left behind by the opposing party: nine weapons were taken, an abundance of ammo, clothes, food, and fuel.[78]

Presidential palace attack

[edit]

At approximately 3:21 pm[80] on 13 March 1957 the student opposition group Directorio Revolucionario 13 de Marzo stormed the Presidential Palace in Havana, attempting to assassinate Batista and overthrow the government. The attack ended in utter failure. The DR's leader, student José Antonio Echeverría, died in a shootout with Batista's forces at the Havana radio station he had seized to spread the news of Batista's anticipated death.[81] The handful of survivors included Dr. Humberto Castelló Aldanás (who later became the Inspector General in the Escambray),[82][better source needed] Rolando Cubela Secades and Faure Chomón (both later Comandantes of the 13 March Movement, centered in the Escambray Mountains of Las Villas Province).[83]

The plan, as explained by Faure Chaumón, was to attack the Presidential Palace and occupy the radio station Radio Reloj at the Radiocentro CMQ Building in order to announce the death of Batista and call for a general strike.[81] The Presidential Palace was to be captured by fifty men under the direction of (brother of Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo) and Faure Chaumón, with support from a group of 100 armed men occupying the tallest buildings in the surrounding area of the Presidential Palace (La Tabacalera, the Sevilla Hotel, the Palace of Fine Arts). However this secondary support operation was not carried out, as the men failed to arrive at the scene due to last-minute hesitation. Although the attackers reached the third floor of the palace, they did not locate or execute Batista.[citation needed]

Humboldt 7 massacre

[edit]

The Humboldt 7 massacre occurred on 20 April 1957 at apartment 201 of the Humboldt 7 residential building when the National Police led by Lt. Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo assassinated four participants who had survived the assault on the Presidential Palace and in the seizure of the Radio Reloj station at the Radiocentro CMQ Building.

Juan Pedro Carbó was sought by police for the assassination of Col. Antonio Blanco Rico, Chief of Batista's secret service.[84][85] Marcos "Marquitos" Rodríguez Alfonso began arguing with Fructuoso, Carbó and Machadito; Joe Westbrook had not yet arrived. Marquitos, who gave the airs to be a revolutionary, was strongly against the revolution and was thus resented by the others. On the morning of 20 April 1957, Marquitos met with lieutenant colonel Esteban Ventura Novo and revealed the location of where the young revolutionaries were, Humboldt 7.[86] After 5:00 pm on 20 April, a large contingent of police officers arrived and assaulted apartment 201, where the four men were staying. The men were not aware that the police were outside. The police rounded up and executed the rebels, who were unarmed.[87]

The incident was covered up until a post-revolution investigation in 1959. Marquitos was arrested and, after a double trial, was sentenced by the Supreme Court to the penalty of death by firing squad in March 1964.[88]

Frank País

[edit]Frank País was a revolutionary organizer affiliated with the 26th of July Movement who had built an extensive underground urban network.[89] He had been tried and acquitted for his role in organizing an unsuccessful uprising in Santiago de Cuba in support of Castro's landing at the end of November in 1956. On 30 June 1957, Frank's younger brother Josué País was killed by the Santiago police.[90][91] During the latter part of July 1957, a wave of systematic police searches forced Frank País into hiding in Santiago de Cuba. On 21 July, País had hid in Raúl Pujol Arencibia's home. An ongoing serach in the area forced the two men to relocate, however. On 30 July he was in a safe house with Pujol Arencibia, despite warnings from other members of the Movement that it was not secure. The Santiago police under Colonel José Salas Cañizares surrounded the building. Frank and Raúl attempted to escape. However, an informant betrayed them as they tried to walk to a waiting getaway car. The police officers drove the two men to the Callejón del Muro (Rampart Lane) and shot them in the back of the head.[92][93] In defiance of Batista's regime, País was buried in the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery[94] in the olive green uniform and red and black armband of 26 July Movement.[citation needed]

In response to the death of País, the workers of Santiago declared a spontaneous general strike. This strike was the largest popular demonstration in the city up to that point. The mobilization of 30 July 1957 is considered one of the most decisive dates in both the Cuban Revolution and the fall of Batista's dictatorship. This day has been instituted in Cuba as the Day of the Martyrs of the Revolution.[95] The Frank País Second Front, the guerrilla unit led by Raúl Castro in the Sierra Maestra was named for the fallen revolutionary.[96] His childhood home at 226 San Bartolomé Street was turned into The Santiago Frank País García House Museum and designated as a national monument.[97] The international airport in Holguín, Cuba also bears his name.

Naval mutiny at Cienfuegos

[edit]On 6 September 1957 elements of the Cuban navy in the Cienfuegos Naval Base staged a rising against the Batista regime. Led by junior officers in sympathy with the 26th of July Movement, this was originally intended to coincide with the seizure of warships in Havana harbour. Reportedly individual officials within the U.S. Embassy were aware of the plot and had promised U.S. recognition if it were successful.[98][h]

By 5:30am the base was in the hands of the mutineers. The 150 naval personnel sleeping at the base joined with the approximately fifty original conspirators, while eighteen officers were arrested. About two hundred 26th of July Movement members and other rebel supporters entered the base from the town and were given weapons. Cienfuegos was in rebel hands for several hours.[99]

By the afternoon Government motorised infantry had arrived from Santa Clara, supported by B-26 bombers given by the United States. Armoured units followed from Havana. After street fighting throughout the afternoon and night the last of the rebels, holding out in the police headquarters, were overwhelmed. Approximately 70 mutineers and rebel supporters were executed and reprisals against civilians added to the estimated total death toll of 300 men.[100]

The use of bombers and tanks recently provided under a US-Cuban arms agreement specifically for use in hemisphere defence, now raised tensions between the two governments.[101]

Escalation and U.S. involvement

[edit]The United States supplied Cuba with planes, ships, tanks, and other technology such as napalm, which was used against the rebels. This would eventually come to an end due to a later arms embargo in 1958.[102] On the other side, the Cuban rebels were supplied by Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito.[103]

According to Tad Szulc, the United States began funding the 26th of July Movement around October or November 1957 and ending around middle 1958. "No less than $50,000" would be delivered to key leaders of the 26th of July Movement,[104] the purpose being to instill sympathies to the United States amongst the rebels in case the movement succeeded.[105]

While Batista increased troop deployments to the Sierra Maestra region to crush the 26 July guerrillas, the Second National Front of the Escambray kept battalions of the Constitutional Army tied up in the Escambray Mountains region. The Second National Front was led by former Revolutionary Directorate member Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo and the "Comandante Yanqui" William Alexander Morgan, who was dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army after going AWOL.[106] Gutiérrez Menoyo formed and headed the guerrilla band after news had broken out about Castro's landing in the Sierra Maestra, and José Antonio Echeverría had stormed the Havana Radio station.[107][108]

Thereafter, on 14 March 1958, the United States imposed an arms embargo on the Cuban government and recalled its ambassador Arthur Gardner, weakening the government's mandate further.[109] Batista's support among Cubans began to fade, with former supporters either joining the revolutionaries or distancing themselves from Batista.

Batista's government often resorted to brutal methods to keep Cuba's cities under control. However, in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro, aided by Frank País, Ramos Latour, Huber Matos, and many others, staged successful attacks on small garrisons of Batista's troops. Castro was joined by CIA connected Frank Sturgis who offered to train Castro's troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26 July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.

In addition, poorly armed irregulars known as escopeteros harassed Batista's forces in the forests and mountains of Oriente Province. The escopeteros also provided direct military support to Castro's main forces by protecting supply lines and by sharing intelligence.[110] Ultimately, the mountains came under Castro's control.[111]

In addition to armed resistance, the rebels sought to use propaganda to their advantage. A pirate radio station called Radio Rebelde ("Rebel Radio") was set up in February 1958, allowing Castro and his forces to broadcast their message nationwide within enemy territory.[112] Castro's affiliation with the New York Times journalist Herbert Matthews created a front page-worthy report on anti-communist propaganda.[113] The radio broadcasts were made possible by Carlos Franqui, a previous acquaintance of Castro who subsequently became a Cuban exile in Puerto Rico.[114]

During this time, Castro's forces remained quite small in numbers, sometimes fewer than 200 men, while the Cuban military and police force had a manpower of around 37,000.[115] Even so, nearly every time the Cuban military fought against the revolutionaries, the army was forced to retreat. The arms embargo imposed by the United States is a significant contributing factor to Batista's weakened forces. The Cuban air force rapidly deteriorated: it could not repair its airplanes without importing parts from the United States.[116]

Final offensives: 1958–1959

[edit]Operation Verano

[edit]Batista finally responded to Castro's efforts with an attack on the mountains called Operation Verano (Summer), known to the rebels as la Ofensiva. The Cuban army sent an upwards of approximately 10,000 soldiers into the mountains, half of them untrained recruits whom had little experience with treking and fighting through rocky terrain.[117] In a series of small skirmishes, Castro's determined guerrillas defeated the Cuban army.

The Battle of El Jigüe, albeit commonly referred to as the Battle of La Plata (1958), was a surprise attack on Fidel's base in Sierra Maestra, planned by Cuban army major general Eulogio Cantillo who put Battalion 17 and Battalion 18, commanded by Fidel's former peer at the University of Havana José Quevedo Pérez, on the front lines.[118] The battle spanned from 11 to 21 July 1958 and is widely considered to be a "turning point" in the revolution.[119]

However, the tide nearly turned on 29 July 1958, when Batista's troops almost destroyed Castro's small army of some 300 men at the Battle of Las Mercedes. With his forces pinned down by superior numbers, Castro asked for, and received, a temporary cease-fire on 1 August. Over the next seven days, while fruitless negotiations took place, Castro's forces gradually escaped from the trap. By 8 August, Castro's entire army had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.

Battle of Las Mercedes

[edit]The Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July–8 August 1958) was the last battle of Operation Verano.[120] The battle was a trap, designed by Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo to lure Fidel Castro's guerrillas into a place where they could be surrounded and destroyed. The battle ended with a cease-fire which Castro proposed and which Cantillo accepted. During the cease-fire, Castro's forces escaped back into the mountains. The battle, though technically a victory for the Cuban army, left the army dispirited and demoralized. Castro viewed the result as a victory and soon launched his own offensive.

Battalion 17 began its pull back on 29 July 1958. Castro sent a column of men under René Ramos Latour to ambush the retreating soldiers. They attacked the advance guard and killed some 30 soldiers but then came under attack from previously undetected Cuban forces. Latour called for help and Castro came to the battle scene with his own column of men. Castro's column also came under fire from another group of Cuban soldiers that had secretly advanced up the road from the Estrada Palma Sugar Mill.

As the battle heated up, General Cantillo called up more forces from Bayamo and Manzanillo and approximately 1,500 troops started heading towards the fighting.[121] However, this force was halted by a column under Che Guevara's command. While some critics accuse Che for not coming to the aid of Latour, Major Bockman argues that Che's move here was the correct thing to do. Indeed, he called Che's tactical appreciation of the battle "brilliant".

By the end of July, Castro's troops were fully engaged and in danger of being wiped out by the vastly superior numbers of the Cuban army. He had lost 70 men, including René Latour,[122] and both he and the remains of Latour's column were surrounded. The next day, Castro requested a cease-fire with General Cantillo, even offering to negotiate an end to the war. This offer was accepted by General Cantillo for reasons that remain unclear.

Batista sent a personal representative to negotiate with Castro on 2 August. The negotiations yielded no result but during the next six nights, Castro's troops managed to slip away unnoticed. On 8 August when the Cuban army resumed its attack, they found no one to fight.

Castro's remaining forces had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.

Battle of Yaguajay

[edit]

In December 1958, Fidel Castro ordered his revolutionary army to go on the offensive against Batista's army. While Castro led one force against Guisa, Masó and other towns, another major offensive was directed at the capture of the city of Santa Clara, the capital of what was then Las Villas Province.

Three columns were sent against Santa Clara under the command of Che Guevara, Jaime Vega, and Camilo Cienfuegos. Vega's column was caught in an ambush and completely destroyed. Guevara's column took up positions around Santa Clara (near Fomento). Cienfuegos's column directly attacked a local army garrison at Yaguajay. Initially numbering just 60 men out of Castro's hardened core of 230, Cienfuegos's group had gained many recruits as it crossed the countryside towards Santa Clara, eventually reaching an estimated strength of 450 to 500 fighters.

The garrison consisted of some 250 men under the command of a Cuban captain of Chinese ancestry, Alfredo Abon Lee.[123] The attack began on 21 December.[124]

Convinced that reinforcements would be sent from Santa Clara, Lee put up a determined defense of his post. The guerrillas repeatedly attempted to overpower Lee and his men, but failed each time. By 26 December Camilo Cienfuegos had become quite frustrated; it seemed that Lee could not be overpowered, nor could he be convinced to surrender. In desperation, Cienfuegos tried using a homemade tank against Lee's position. The "tank" was actually a large tractor encased in iron plates with attached makeshift flamethrowers on top. It, too, proved unsuccessful.[125]

Finally, on 30 December Lee ran out of ammunition and was forced to surrender his force to the guerrillas.[126] The surrender of the garrison was a major blow to the defenders of the provincial capital of Santa Clara. The next day, the combined forces of Cienfuegos, Guevara, and local revolutionaries under William Alexander Morgan captured the city in a fight of vast confusion.

Battle of Guisa

[edit]On the morning of 20 November 1958, a convoy of the Batista soldiers began its usual journey from Guisa. Shortly after leaving that town, located in the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, the rebels attacked the caravan.[127]

Guisa was 12 kilometers from the Command Post of the Zone of Operations, located on the outskirts of the city of Bayamo. Nine days earlier, Fidel Castro had left the La Plata Command, beginning an unstoppable march east with his escort and a small group of combatants.[i]

On 19 November, the rebels arrived in Santa Barbara. By that time, there were approximately 230 combatants. Fidel gathered his officers to organize the siege of Guisa, and ordered the placement of a mine on the Monjarás bridge, over the Cupeinicú river. That night the combatants made a camp in Hoyo de Pipa. In the early morning, they took the path that runs between the Heliografo hill and the Mateo Roblejo hill, where they occupied strategic positions. In the meeting on the 20th, the army lost a truck, a bus, and a jeep. Six were killed and 17 prisoners were taken, three of them wounded. At around 10:30 am, the military Command Post located in the Zone of Operations in Bayamo sent a reinforcement made up of Co. 32, plus a platoon from Co. L and another platoon from Co. 22. This force was unable to advance for the resistance of the rebels. Fidel ordered the mining of another bridge over a tributary of the Cupeinicú River. Hours later the army sent a platoon from Co. 82 and another platoon from Co. 93, supported by a T-17 tank.[128][j][129]

1958 Cuban general election

[edit]

General elections were held in Cuba on 3 November 1958.[130] The three major presidential candidates were Carlos Márquez Sterling of the Partido del Pueblo Libre, Ramón Grau of the Partido Auténtico and Andrés Rivero Agüero of the Coalición Progresista Nacional. There was also a minor party candidate on the ballot, Alberto Salas Amaro for the Party of Cuban Unity.[131] Although Andrés Rivero Agüero won the presidential election with 70% of the vote, he was unable to take office due to the Cuban Revolution.[132]

Rivero Agüero was due to be sworn in on 24 February 1959. In a conversation between him and the American ambassador Earl E. T. Smith on 15 November 1958, he called Castro a "sick man" and stated it would be impossible to reach a settlement with him. Rivero Agüero also said that he planned to restore constitutional government and would convene a Constitutional Assembly after taking office.[133]

This was the last competitive election in Cuba, the 1940 Constitution of Cuba, the Congress and the Senate of the Cuban Republic, were quickly dismantled shortly thereafter.

Battle of Santa Clara and Batista's flight

[edit]On 31 December 1958, the Battle of Santa Clara took place in a scene of great confusion. The city of Santa Clara fell to the combined forces of Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and Revolutionary Directorate (RD) rebels led by Comandantes Rolando Cubela, Juan "El Mejicano" Abrahantes Fernández, and William Alexander Morgan.[134][135] News of these defeats caused Batista to panic. He fled Cuba by air for the Dominican Republic just hours later on 1 January 1959.[136] Comandante William Alexander Morgan, leading RD rebel forces, continued fighting as Batista departed, and had captured the city of Cienfuegos by 2 January.[137]

Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo entered Havana's Presidential Palace, proclaimed the Supreme Court judge Carlos Piedra as the new president, and began appointing new members to Batista's old government.[138][139]

Aftermath

[edit]Rebel victory

[edit]

Castro learned of Batista's flight in the morning of 1 January, and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[140]

After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution on 1 January 1959, dozens of Fulgencio Batista's supporters and members of the armed forces and police were arrested and accused of war crimes and other abuses.[141] On January 11, a revolutionary court in Santiago de Cuba sentenced 4 individuals to death after a 4-hour summary trial.[141] The court was also presided over by Rebel Army Commander Raúl Castro, who was in command of the Oriente province. The Santiago rebels sentenced 68 more men to the death penalty, Raúl Castro declared that "if one was guilty, all were also guilty."[141] The men were shot in a mass execution at San Juan Hill, on January 12, 1959.[142]

Provisional Government

[edit]

The Cuban Revolution gained victory on 1 January 1959,[143] and liberal lawyer Manuel Urrutia Lleó returned from exile in Venezuela to take up residence in the presidential palace.[144]. Urrutia Lleó had campaigned against Batista's governing during the 1950s and supported the July 26 Movement, before serving as president in the first revolutionary government of 1959.[145] The new provisional government consisted of other Cuban political veterans and pro-business liberals including José Miró, who was appointed as prime minister.[146]

Once in power, Urrutia swiftly began a program of closing all brothels, gambling outlets and the national lottery, arguing that these had long been a corrupting influence on the state. The measures drew immediate resistance from the large associated workforce. The disapproving Castro, then commander of Cuba's new armed forces, intervened to request a stay of execution until alternative employment could be found.[147]

Disagreements soon arose in the new government concerning pay cuts, which were imposed on all public officials on Castro's demand. The disputed cuts included a reduction of the $100,000 a year presidential salary Urrutia had inherited from Batista.[148] On 16 February, following the surprise resignation of Miró, Castro had assumed the role of prime minister; this strengthened his power and rendered Urrutia increasingly a figurehead president.[149] As Urrutia's participation in the legislative process declined, other unresolved disputes between the two leaders continued to fester. His belief in the restoration of elections was rejected by Castro, who felt that they would usher in a return to the old discredited system of corrupt parties and fraudulent balloting that had marked the Batista era.[150][page needed]

On April 9, 1959, Fidel Castro proclaimed that the elections, which were promised to happen after the revolution, were to be delayed by fifteen months. This delay was deemed necessary in order for the provisional government to focus on domestic reforms.[151]

Urrutia was then accused by the Avance newspaper of buying a luxury villa, which was portrayed as a frivolous betrayal of the revolution and led to an outcry from the general public. He denied the allegation issuing a writ against the newspaper in response. The story further increased tensions between the various factions in the government, though Urrutia asserted publicly that he had "absolutely no disagreements" with Fidel Castro. Urrutia attempted to distance the Cuban government (including Castro) from the growing influence of the communists within the administration, making a series of critical public comments against the latter group. Whilst Castro had not openly declared any affiliation with the Cuban communists, Urrutia had been a declared anti-communist since they had refused to support the insurrection against Batista,[152] stating in an interview, "If the Cuban people had heeded those words, we would still have Batista with us ... and all those other war criminals who are now running away".[150][page needed] Castro resigned from his position as commander-in-chief, citing the controversy around Urrutia as cause. In the aftermath of Castro's resignation, angry mobs surrounded the Presidential Palace, and Urrutia then resigned. Castro was reinstated into his position, and a growing political sentiment in Cuba associated Fidel Castro with the only source of legitimate power.[153] Fidel Castro soon replaced Manuel Urrutia with Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado as President of Cuba. Dorticós was a member of the Popular Socialist Party.[151]

Legacy

[edit]Relations with the United States

[edit]

The Cuban Revolution was a crucial turning point in U.S.-Cuban relations. Although the United States government was initially willing to recognize Castro's new government,[154] it soon came to fear that Communist insurgencies would spread through the nations of Latin America, as they had in Southeast Asia.[155] Meanwhile, Castro's government resented the Americans for providing aid to Batista's government during the revolution.[156][k] After the revolutionary government nationalized all U.S. property in Cuba in August 1960, the American Eisenhower administration froze all Cuban assets on American soil, severed diplomatic ties and tightened its embargo of Cuba in January 1961.[157] The Key West–Havana ferry shut down. In 1961, the U.S. government launched the Bay of Pigs Invasion, in which Brigade 2506 (a CIA-trained force of 1,500 soldiers, mostly Cuban exiles) landed on a mission to oust Castro; the attempt to overthrow Castro failed, with the invasion being repulsed by the Cuban military.[158] The U.S. embargo against Cuba is still in force as of 2020, although it underwent a partial loosening during the Obama administration, only to be strengthened in 2017 under Trump.[159] The U.S. began efforts to normalize relations with Cuba in the mid-2010s,[160] and formally reopened its embassy in Havana after over half a century in August 2015.[161] The Trump administration reversed much of the Cuban Thaw by severely restricting travel by US citizens to Cuba and tightening the US government's embargo against the country.[162][163]

I believe that there is no country in the world, including the African regions, including any and all the countries under colonial domination, where economic colonization, humiliation and exploitation were worse than in Cuba, in part owing to my country's policies during the Batista regime. I believe that we created, built and manufactured the Castro movement out of whole cloth and without realizing it. I believe that the accumulation of these mistakes has jeopardized all of Latin America. The great aim of the Alliance for Progress is to reverse this unfortunate policy. This is one of the most, if not the most, important problems in America foreign policy. I can assure you that I have understood the Cubans. I approved the proclamation which Fidel Castro made in the Sierra Maestra, when he justifiably called for justice and especially yearned to rid Cuba of corruption. I will go even further: to some extent it is as though Batista was the incarnation of a number of sins on the part of the United States. Now we shall have to pay for those sins. In the matter of the Batista regime, I am in agreement with the first Cuban revolutionaries.

Relations with the Soviet Union

[edit]Following the American embargo, the Soviet Union became Cuba's main ally. The Soviet Union did not initially want anything to do with Cuba or Latin America until the United States had taken an interest in dismantling Castro's communist government. At first, many people in the Soviet Union did not know anything about Cuba, and those that did, saw Castro as a "troublemaker" and the Cuba Revolution as "one big heresy".[165] There were three big reasons why the Soviet Union changed their attitudes and finally took interest in the island country. First was the success of the Cuban Revolution, to which Moscow responded with great interest as they understood that if a communist revolution was successful for Cuba, it could be successful elsewhere in Latin America. So from then on the Soviets began looking into foreign affairs in Latin America. Second, after learning about the United States' aggressive plan to deploy another Guatemala scenario in Cuba, the Soviet opinion quickly changed feet.[165] Third, Soviet leaders saw the Cuban Revolution as first and foremost an anti–North American revolution which of course whet their appetite as this was during the height of the cold war and the Soviet, US battle for global dominance was at its apex.[166]

The Soviets' attitude of optimism changed to one of concern for the safety of Cuba after it was excluded from the inter-American system at the conference held at Punta del Este in January 1962 by the Organization of American States.[166] This coupled with the threat of a United States invasion of the island was really the turning point for Soviet Concern, the idea was that should Cuba be defeated by the United States it would mean defeat for the Soviet Union and for Marxism–Leninism. If Cuba were to fall, "other Latin American countries would reject us, claiming that for all our might the Soviet Union had not been able to do anything for Cuba except to make empty protests to the United Nations" wrote Khrushchev.[166] The Soviet attitude towards Cuba changed to concern for the safety of the island nation because of increased US tensions and threats of invasion making the Soviet–Cuban relationship superficial insofar as it only cared about denying the US power in the region and maintaining Soviet supremacy.[167] All of these events led to the two countries quickly developing close military and intelligence ties, which culminated in the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba in 1962, an act which triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

The aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis saw international embarrassment for the Soviet Union,[168] and many countries including Communist countries were quick to criticize Moscow's handling of the situation. In a letter that Khrushchev writes to Castro in January of the following year (1963), after the end of conflict, he talks about wanting to discuss the issues in the two countries' relations. He writes attacking voices from other countries, including socialist ones, blaming the USSR of being opportunistic and self-serving. He explained the decision to withdraw missiles from Cuba, stressing the possibility of advancing Communism through peaceful means. Khrushchev underlined the importance of guaranteeing against an American attack on Cuba and urged Havana to focus on economic, cultural, and technological development to become a shining beacon of socialism in Latin America. In closing he invites Fidel Castro to visit Moscow and discuss the preparations for such a trip.[169]

The 1970s and 1980s were somewhat of an enigma in the sense that the two decades were filled with the most prosperity in Cuba's history, and it adopted and enacted several brutal features of socialist regimes from the Eastern Bloc.[citation needed] This period is marked as the Sovietization of the 1970s and 1980s. On 11 July 1972, Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), officially joining their trade with the Soviet Union's socialist trade bloc.[170] That along with increased Soviet subsidies, better trade terms, and better, more practical domestic policy led to several years of prosperous growth. Moreover, Cuba was able to strengthen its foreign policy with both communistic, anti-US imperial and non-communistic countries (albeit not including those in North America and Latin America).[171]

It has, however, come into question as to whether this alliance benefitted both Cuba and the Soviet Union equally. For one, there is the belief that the latter utilized the Cuban government and citizens to gain an advantage in foreign military operations, while Cuba received more consequence than reward in return.[172][l] In addition, was perceived as having "betrayed the revolution" by the United States, this negative perception of the country eventually leading to trade embargos and active isolation of its government.[171] Whilst Cuba had undoubtedly economically benefitted from its connection with the Soviet Union, the short- and long-term impact has been the subject of discussion amongst scholars.

Cuba maintained close links to the Soviets until the Soviet Union's collapse and disbandment of COMECON in 1991. The end of Soviet economic aid and the loss of its trade partners in the Eastern Bloc led to an economic crisis and period of shortages known as the Special Period in the Time of Peace in Cuba.[173]

Current day relations with Russia, formerly the Soviet Union, ended in 2002 after the Russian Federation closed an intelligence base in Cuba over budgetary concerns. However, in the last decade, relations have increased in recent years after Russia faced international backlash from the West over the situation in Ukraine in 2014. In retaliation for NATO expansion towards the east, Russia has sought to create these same agreements in Latin America. Russia has specifically sought greater ties with Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Brazil, and Mexico. Currently, these countries maintain close economic ties with the United States. In 2012, Putin decided that Russia focus its military power in Cuba like it had in the past. Putin is quoted saying, "Our goal is to expand Russia's presence on the global arms and military equipment market. This means expanding the number of countries we sell to and expanding the range of goods and services we offer."[174]

Global influence

[edit]The greatest threat presented by Castro's Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation ... his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia.

— Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, 27 April 1964[175]

Castro's victory and post-revolutionary foreign policy had global repercussions as influenced by the expansion of the Soviet Union into Eastern Europe after the 1917 October Revolution. In line with his call for revolution in Latin America and beyond against imperial powers, laid out in his Declarations of Havana, Castro immediately sought to "export" his revolution to other countries in the Caribbean and beyond, sending weapons and troops[176] to Algerian rebels as early as 1960.[177] In the following decades, Cuba became heavily involved in supporting Communist insurgencies and independence movements in many developing countries, sending military aid to insurgents in Ghana, Nicaragua,[178] North Yemen,[179] and Angola,[180] among others. Castro's intervention in the Angolan Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s was particularly significant, involving as many as 60,000 Cuban soldiers.[181]

Historiography

[edit]Ideology

[edit]

At the time of the revolution various sectors of society supported the revolutionary movement from communists to business leaders and the Catholic Church.[182]

The beliefs of Fidel Castro during the revolution have been the subject of much historical debate. Fidel Castro was openly ambiguous about his beliefs at the time. Some orthodox historians argue Castro was a communist from the beginning with a long-term plan; however, others have argued he had no strong ideological loyalties. Leslie Dewart has stated that there is no evidence to suggest Castro was ever a communist agent. Levine and Papasotiriou believe Castro believed in little outside of a distaste for American imperialism. As evidence for his lack of communist leanings they note his friendly relations with the United States shortly after the revolution and him not joining the Cuban Communist Party during the beginning of his land reforms.[182]

At the time of the revolution the 26th of July Movement involved people of various political persuasions, but most were in agreement and desired the reinstatement of the 1940 Constitution of Cuba and supported the ideals of Jose Marti. Che Guevara commented to Jorge Masetti in an interview during the revolution that "Fidel isn't a communist" also stating "politically you can define Fidel and his movement as 'revolutionary nationalist'. Of course he is anti-American, in the sense that Americans are anti-revolutionaries".[183]

Women's roles

[edit]

The importance of women's contributions to the Cuban Revolution is reflected in the very accomplishments that allowed the revolution to be successful, from the participation in the Moncada Barracks, to the Mariana Grajales all-women's platoon that served as Fidel Castro's personal security detail. Tete Puebla, second in command of the Mariana Grajales Women's Platoon, has said:

Women in Cuba have always been on the front line of the struggle. At Moncada we had Yeye (Haydée Santamaría) and Melba (Hernández). With the Granma (yacht) and 30 November we had Celia, Vilma, and many other compañeras. There were many women comrades who were tortured and murdered. From the beginning there were women in the Revolutionary Armed Forces. First they were simple soldiers, later sergeants. Those of us in the Mariana Grajales Platoon were the first officers. The ones who ended the war with officers' ranks stayed in the armed forces.[184][page needed]

Before the Mariana Grajales Platoon was established, the revolutionary women of the Sierra Maestra were not organized for combat and primarily helped with cooking, mending clothes, and tending to the sick, frequently acting as couriers, as well as teaching guerrillas to read and write.[184][page needed]

Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández were the only women who participated in the attack on the Moncada Barracks, afterward acting alongside Natalia Revuelta, and Lidia Castro (Fidel Castro's sister) to form alliances with anti-Batista organizations, as well as the assembly and distribution of "History Will Absolve Me".[185] Celia Sánchez and Vilma Espin were leading strategists and highly skilled combatants who held essential roles throughout the revolution. Tete Puebla, founding member and second in command of the Mariana Grajales Platoon, said of Celia Sánchez, "When you speak of Celia, you've got to speak of Fidel, and vice versa. Celia's ideas touched almost everything in the Sierra."[184][page needed]

Related archival collections

[edit]There were many foreign presences in Cuba during this time. Esther Brinch was a Danish translator for the Danish government in 1960's Cuba. Brinch's work covered the Cuban Revolution and Cuban Missile Crisis.[186] A collection of Brinch's archival materials is housed at the George Mason University Special Collections Research Center.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "After a general amnesty in favor of those who took part in the August revolution, Magoon certainly behaved very often as if he were the court of appeal, mitigating the severity of the Spanish legislation and the incorruptibility of the judiciary." (English translation)

- ^ "Before coming to power, Menocal was respected as a capable man, but he was distrusted for being too closely identified with the United States. As president he became known as a man more committed to bribery and corruption than Gómez. It was said that when he took office as president, he had one million dollars, and when he left in 1921 he had forty." (English translation)

- ^ "The university was a good example of corruption, and was full of 'professors' who were paid without teaching, and were mere political extras or relatives of the president." (English translation)

- ^ "Fidel Castro argued: 'If, in the face of these flagrant crimes and confessions of treachery and sedition, he is not tried and punished, how will this court later try any citizen for sedition or rebelliousness against this unlawful crime, the result of unpunished treason? That would be absurd, inadmissible, monstrous in the light of the most elementary principles of justice'." [52]

- ^ The number of rebels recruited for the Moncada Barracks attack is not certain. It is noted by Quirk that the approximate range is between 126 and 167, per published figures.

- ^ "The return to inaction brought new student riots in Santiago and Havana. [...] Many students were arrested; many were wounded; some were beaten and others tortured; on December 10, Raúl Cervantes, president of the Juventud Ortodoxa, was shot dead by the police in Ciego de Ávila. [...] In addition, the student protests were immediately followed by the protests of the sugar workers, for economic reasons." (English translation)[64]

- ^ The number ranges from 30 to 100, based on publishing sources.

- ^ "Castro, Raúl Chibás and Pazos, in the Sierra manifesto, had condemned any idea that a sector of the Armed Forces themselves could help overthrow Batista. Of course, if such a coup were to take place, it would damage Castro's chances of coming to power. But in September, a sector of the Navy made a serious attempt in Cienfuegos to overthrow the regime through the naval officers stationed there, in collaboration with the 26th of July Movement, the auténticos and others." (English translation) [98]

- ^ Sierra Maestra, Dic. 1, 58 2 y 45 p.m. Coronel García Casares: I am writing these lines to inquire about a man of ours [Lieutenant Orlando Pupo] who was almost certainly taken prisoner by your forces. The event happened like this: after the Army units withdrew, I sent a vanguard to explore in the direction of the Furnace. Further back I set off on the same road where our vanguard was going. By chance said vanguard had taken another road and came to the road behind us. As I expected, I sent a man to catch up with her to tell her to stop before reaching the Furnace. The messenger left with the belief that it was going ahead and therefore would be completely unnoticed of the danger; He was also traveling on horseback, with the consequent noise of his footsteps. Once the error was discovered, everything possible was done to warn him of the situation, but he had already reached the danger zone. They waited several hours for him and he did not return. Today it has not appeared. A gunshot was also heard at night. I am sure that he was taken prisoner; I confess that even the fear that he would have been later killed. I'm worried about the shot that was heard. And I know that when it is a post that fires it is never limited to a single shot in these cases. I have been explicit in the narration of the incident so that you can have sufficient evidence. I hope I can count on your chivalry, to prevent that young man from being assassinated uselessly, if he was not killed last night. We all feel special affection for that partner and we are concerned about his fate. I propose that you return him to our lines, as I have done with hundreds of military personnel, including numerous officers. Military honor will win with that elemental gesture of reciprocity. "Politeness does not remove the brave." Many painful events have occurred in this war because of some unscrupulous or honorable military personnel, and believe me that the Army needs men and gestures to compensate for those blemishes. It is because I have a high opinion of you that I decide to talk to you about this case, in the assurance that you will do what is within your power. If some formal inconvenience arises, it can be done in the form of an exchange, for one or more of the soldiers we took prisoner during the action of Guisa. Sincerely, Fidel Castro R.

- ^ The following is an excerpt from a speech given on 1 December 1958 by Fidel Castro, broadcast on the Rebel Army's radio station, which reported on the victory of the revolutionary forces in the battle of Guisa in the Sierra Maestra mountains, one of the turning points in the revolutionary war that spelled the doom of the Batista dictatorship. A month later the dictatorship collapsed and Rebel Army forces entered Havana:

Yesterday at 9 p.m., after ten days of intense combat, our forces entered Guisa; the battle took place within sight of Bayamo, where the dictatorship has its command center and the bulk of its forces:

The action at Guisa began at exactly 8:30 a.m. on 20 November when our forces intercepted an enemy patrol that made the trip from Guisa to Bayamo on a daily basis. The patrol was turned back, and that same day the first enemy reinforcements arrived. At 4:00 p.m. a T-17 thirty-ton tank was destroyed by a powerful land mine: the impact of the explosion was such that the tank was thrown several meters through the air, falling forward with its wheels up and its cab smashed in on the pavement of the road. Hours before that, a truck full of soldiers had been blown up by another mine. At 6:00 p.m. the reinforcements withdrew.

On the following day, the enemy advanced, supported by Sherman tanks, and was able to reach Guisa, leaving a reinforcement in the local garrison.

On the 22nd, our troops, exhausted from two days of fighting, took up positions on the road from Bayamo to Guisa.

On the 23rd, an enemy troop tried to advance along the road from Corojo and was repulsed. On the 25th, an infantry battalion, led by two T-17 tanks, advanced along the Bayamo-Guisa road, guarding a convoy of fourteen trucks.

At two kilometers from this point, the rebel troops fired on the convoy, cutting off its retreat, while a mine paralyzed the lead tank.

Then began one of the most violent combats that has taken place in the Sierra Maestra. Inside the Guisa garrison, the complete battalion that came in reinforcement, along with two T-17 tanks, was now within the rebel lines. At 6:00 p.m., the enemy had to abandon all its trucks, using them as a barricade tightly encircling the two tanks. At 10:00 p.m., while a battery of mortars attacked them, rebel recruits, armed with picks and shovels, opened a ditch in the road next to the tank that had been destroyed on the 20th, so that between the tank and the ditch, the other two T-17 tanks within the lines were prevented from escaping.

They remained isolated, without food or water, until the morning of the 27th when, in another attempt to break the line, two battalions of reinforcements brought from Bayamo advanced with Sherman tanks to the site of the action. Throughout the day of the 27th the reinforcements were fought. At 6:00 p.m., the enemy artillery began a retreat under cover of the Sherman tanks, which succeeded in freeing one of the T-17 tanks that were inside the lines; on the field, full of dead soldiers, an enormous quantity of arms was left behind, including 35,000 bullets, 14 trucks, 200 knapsacks, and a T-17 tank in perfect condition, along with abundant 37-millimeter cannon shot. The action wasn't over – a rebel column intercepted the enemy in retreat along the Central Highway and caused it new casualties, obtaining more ammunition and arms.

On the 28th, two rebel squads, led by the captured tank, advanced toward Guisa. At 2:30 a.m. on the 29th, the rebels took up positions, and the tank managed to place itself facing the Guisa army quarters. The enemy, entrenched in numerous buildings, gave intense fire. The tank's cannon had already fired fifty shots when two bazooka shots from the enemy killed its engine, but the tank's cannon continued firing until its ammunition was exhausted and the men inside lowered the cannon tube. Then occurred an act of unparalleled heroism: rebel Lieutenant Leopoldo Cintras Frías, who was operating the tank's machine gun, removed it from the tank, and despite being wounded, crawled under intense crossfire and managed to carry away the heavy weapon.

Meanwhile, that same day, four enemy battalions advanced from separate points: along the road from Bayamo to Guisa, along the road from Bayamo to Corojo, and along the one from Santa Rita to Guisa.

All of the enemy forces from Bayamo, Manzanillo, Yara, Estrada Palma, and Baire were mobilized to smash us. The column that advanced along the road from Corojo was repulsed after two hours of combat. The advance of the battalions that came along the road from Bayamo to Guisa was halted, and they encamped two kilometers from Guisa; those that advanced along the road from Corralillo were also turned back.

The battalions that encamped two kilometers from Guisa tried to advance during the entire day of the 30th; at 4:00 p.m., while our forces were fighting them, the Guisa garrison abandoned the town in hasty flight, leaving behind abundant arms and armaments. At 9:00 p.m., our vanguard entered the town of Guisa. Enemy supplies seized included a T-17 tank—captured, lost, and recaptured; 94 weapons (guns and machine guns, Springfield and Garand); 12 60-millimeter mortars; one 91-millimeter mortar; a bazooka; seven 30-caliber tripod machine guns; 50,000 bullets; 130 Garand grenades; 70 howitzers of 60- and 81-millimeter mortar; 20 bazooka rockets; 200 knapsacks, 160 uniforms, 14 transport trucks; food; and medicine.

The army took two hundred losses counting casualties and wounded. We took eight compañeros who died heroically in action, and seven wounded.

A squadron of women, the "Mariana Grajales", fought valiantly during the ten days of action, resisting the aerial bombardment and the attack by the enemy artillery.

Guisa, twelve kilometers from the military port of Bayamo, is now free Cuban territory.

- ^ Angered from the American government's willingness to assist Batista by giving arms, Castro wrote the following letter dated 5 June 1958: "The Americans are going to pay dearly for what they’re doing. When this war is over, I’ll start a much longer and bigger war of my own: the war I’m going to fight against them. That will be my true destiny." [156]

- ^ An instance of fatal consequence became evident in the aftermath of Cuban involvement in Angola and Ethiopia in the late 1970s into the early 1980s is an example, with the 1981 dengue fever outbreak being attributed to returning Cuban soldiers who may have been exposed. This, however, does not take away from the fact that Cuba had their own goals with this strengthened connection with Africa through the Soviet Union. It is noted that Cuba long supported the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, and there had been significant focus in asserting the ethnic and cultural similarities between Cubans and Africans—furthered by Fidel describing Cubans as "Latin-African people".[172]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dixon & Sarkees 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Jowett 2019, p. 309.

- ^ Bercovitch & Jackson 1997.

- ^ Singer & Small 1974.

- ^ Sivard 1987.

- ^ Delgado Legon, Elio (26 January 2017). "Massacres during Batista's Dictatorship". Havana Times. Managua, Nicaragua. Archived from the original on 9 November 2024. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Kapcia 2021, p. 15–19.

- ^ "Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'". All Things Considered. NPR. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2024. Retrieved 9 November 2024.