Atherton, California

Atherton, California | |

|---|---|

| Town of Atherton | |

Holbrook-Palmer Park | |

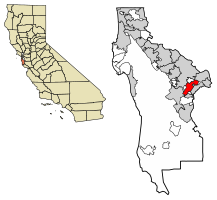

Location of Atherton in San Mateo County, California | |

| Coordinates: 37°27′31″N 122°12′0″W / 37.45861°N 122.20000°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Mateo |

| Incorporated | September 12, 1923[2] |

| Named for | Faxon Dean Atherton[2] |

| Government | |

| • City council[5] |

|

| • Assemblymember | Alex Lee (D) (24th)[3] |

| • State Senator | Josh Becker (D) (13th)[3] |

| • U.S. Rep. | Anna Eshoo (D) (16th)[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.05 sq mi (13.07 km2) |

| • Land | 5.02 sq mi (12.99 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) 0.63% |

| Elevation | 59 ft (18 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 7,188 |

| • Density | 1,433.01/sq mi (553.28/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code[7] | 94027 |

| Area code[8] | 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-03092 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1657960, 2411651 |

| Website | www |

Atherton (/ˈæθərtən/ ATH-ər-tən) is an incorporated town in San Mateo County, California, United States. Its population was 6,823 as of July 2023. The town's zoning regulations permit only one single-family home per acre, and prohibit sidewalks.[9]

Atherton is known for its wealth; in 1990 and 2019,[10] Atherton was ranked as having the highest per capita income among U.S. places that have a population between 2,500 and 9,999,[11] and the area covered by its ZIP Code is regularly ranked as having the highest cost of living in the United States.[12][13][14][15] In 2023, the Atherton ZIP Code had the highest median home prices in the United States, at $7,950,000.[16]

History

[edit]The entire area was originally part of the Rancho de las Pulgas.

During the 1860s, Atherton was known as Fair Oaks. In 1923, it was decided to rename the town in honor of Faxon Dean Atherton, a former 19th century landowner on the south peninsula.[17]

Lawsuit against the electrification of Caltrain

[edit]The town has been involved in lawsuits to block or delay the introduction of California High-Speed Rail.[18][19] Atherton was an early and vocal opponent of the electrification of the U.S. commuter railroad Caltrain, which serves cities in the San Francisco Peninsula and Silicon Valley. Residents opposed electrification and the proposed high-speed rail route because the overhead electrical lines would require tree removal and the town could potentially be divided by the closing of the two grade crossings at Fair Oaks Lane and Watkins Avenue.[20]

In February 2015, shortly after the project received environmental clearance from the state, Atherton sued Caltrain, alleging the agency's environmental impact review was inadequate and that its collaboration with the CHSRA should be further vetted.[21] In July 2015, the suit proceeded after Caltrain's request to the Surface Transportation Board to exempt it from California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) guidelines was denied. Atherton reiterated its opposition to electrification on the basis that overhead wires would require removing a significant number of heritage trees, and city representatives asserted that "newer, cleaner, more efficient diesel trains" should supplant plans for "century-old catenary electrical line technology". Atherton mayor Rick De Golia was quoted as saying "Caltrain is locked into an old technology and 20th century thinking".[22] After Caltrain issued infrastructure and rolling stock contracts in July 2016, Atherton representatives did not file a temporary restraining order to halt those contracts, preferring to let the suit proceed to a hearing.[23] In September 2016, Contra Costa County Superior Court Judge Barry Goode sided with Caltrain, ruling that the electrification project did not hinge on the high-speed rail project's success, and was thus independent from the latter.[24][25]

Atherton sued CHSRA again in December 2016, stating that using bond money intended for high-speed rail for CalMod was a material change in usage and therefore was unconstitutional because such a change would require voter approval first.[26] In response, the California Legislature allowed the funding to be redirected by passing Assembly Bill No. 1889, which had been championed by Assemblymember Kevin Mullin in 2015.[27] Mullin noted "this entire Caltrain corridor is the epicenter of the innovation economy and it's a job creation and economic engine. This electrification project, I would argue, is monumental with regard to dealing with [increased traffic and environmental impacts] effectively and efficiently."[26]

The Caltrain station closed in 2020.[28][29]

Land use and housing

[edit]Atherton is the wealthiest city in the United States.[30][11] According to the San Francisco Chronicle, "the town's ascendance stems largely from its single-family zoning, 1-acre-minimum lot sizes, flat land, streamlined permits and changing buyer demographics — which have translated into soaring house sizes and skyrocketing prices."[31] There is no commercial zoning in the town, thus there are no restaurants, shops or grocery stores.[32] There are no sidewalks in Atherton, only road lanes.[33]

Until 2022, the town's zoning regulations permitted only one single-family home per acre and prohibit sidewalks.[9] Partly as a result of these regulations, the average home price in the city in recent years was more than 7.5 million dollars.[34] Many of the inhabitants have strongly opposed proposals to permit more housing construction.[9] Among those include Golden State Warriors player Steph Curry.[35] However, with the passage of SB 9 in 2022, the zoning regulations that limit how many units can be built on a property were nullified.[36]

In 2022, the town blocked a proposal to build 131 multifamily housing units in the town in response to strong criticism of the proposal by the city's inhabitants.[37] Advocates for the construction of additional homes have criticized Atherton as being a NIMBY town.[32][37] In 2022, California Governor Gavin Newsom singled out Atherton in a speech for its restrictive housing policies.[38] The mayor said in 2022 that they were focusing on building affordable housing for staff and teachers at the city's eight schools.[39]

In February 2023, the Atherton City Council approved a housing plan with 348 mixed-income housing units. Under California law, the units must be built over the next eight years, and the city must reserve 148 units for occupancy by "very low income" or "low income" individuals, 56 units for “moderate income” individuals, and 144 units for “above moderate income” individuals.[40]

As of November 2022, Atherton's stated land-use goal is to “preserve the Town's character as a scenic, rural, thickly wooded residential area with abundant open space."[41]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 5.0 square miles (13 km2), of which 5.0 square miles (13 km2) is land and 0.03 square miles (0.078 km2), comprising 0.63%, is water.

Atherton lies two miles (3.2 km) southeast of Redwood City, and 18 miles (29 km) northwest of San Jose. The town is considered to be part of the San Francisco metropolitan area.

Demographics

[edit]About 73% of the city's inhabitants are ethnically non-Hispanic white;[42] this makes it among the safest cities in Silicon Valley.[39]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1,324 | — | |

| 1940 | 1,908 | 44.1% | |

| 1950 | 3,630 | 90.3% | |

| 1960 | 7,717 | 112.6% | |

| 1970 | 8,085 | 4.8% | |

| 1980 | 7,797 | −3.6% | |

| 1990 | 7,163 | −8.1% | |

| 2000 | 7,194 | 0.4% | |

| 2010 | 6,914 | −3.9% | |

| 2020 | 7,188 | 4.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] | |||

2010

[edit]At the 2010 census Atherton had a population of 6,914. The population density was 1,369.5 inhabitants per square mile (528.8/km2). The racial makeup of Atherton was 5,565 (80.5%) White, 75 (1.1%) African American, 7 (0.1%) Native American, 911 (13.2%) Asian, 45 (0.7%) Pacific Islander, 95 (1.4%) from other races, and 216 (3.1%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 268 people (3.9%).[44]

The census reported that 6,529 people (94.4% of the population) lived in households, 385 (5.6%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and no one was institutionalized.

There were 2,330 households, 787 (33.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 1,755 (75.3%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 109 (4.7%) had a female householder with no husband present, 48 (2.1%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 34 (1.5%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 15 (0.6%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 321 households (13.8%) were one person and 178 (7.6%) had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.80. There were 1,912 families (82.1% of households); the average family size was 3.03.

The age distribution was 1,543 people (22.3%) under the age of 18, 579 people (8.4%) aged 18 to 24, 966 people (14.0%) aged 25 to 44, 2,264 people (32.7%) aged 45 to 64, and 1,562 people (22.6%) who were 65 or older. The median age was 48.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.6 males. For every 100 women age 18 and over, there were 95.3 men.

The median household income was in excess of $250,000, the highest of any place in the United States.[45] The per capita income for the town was $128,816. About 2.9% of families and 5.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.6% of those under age 18 and 5.4% of those age 65 or over.

There were 2,530 housing units at an average density of 501.1 per square mile, of the occupied units 2,116 (90.8%) were owner-occupied and 214 (9.2%) were rented. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.9%. 5,921 people (85.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 608 people (8.8%) lived in rental housing units.

Forbes ranked Atherton as second on its list of America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes in 2010, listing median house price as over $2,000,000.[46]

2020

[edit]At the 2020 census, Atherton had a population of 7,193 and 2,252 households, and the homeowner vacancy rate was 0%. The population density was 1,424.3 inhabitants per square mile (549.9/km2).

There was an average 2.94 people per household, 89.2% of homes were owner occupied and 10.8% were renter occupied. The racial makeup of Atherton was 5,403 (75%) White, 1,655 (23%) Asian, 124 (1.7%) African American, 18 (0.3%) Native American, 107 (1.5%) Pacific Islander, 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 540 (7.5%) people.

The median age was 49. For every 100 females there were 100.1 men.

The age distribution was 1,472 people (20.5%) under the age of 18, 862 people (5.6%) aged 18 to 24, 932 people (12.9%) aged 25 to 44, 2,123 (29.5%) aged 45–64 and 1,813 people (25.2%) over the age of 65.

Median income for a household was over $250,000. Males had a median income $102,192 versus $53,882 for females. About 1.1% of families and 2.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 0.5% of those under the age of 18 and 1.1% of those 65 years or over.[47][48]

Property Shark ranked Atherton first for the fourth year in a row as the most expensive ZIP code in the United States in 2022, with the median home price at $7,900,000.[49][50]

Arts and culture

[edit]There are a number of active community organizations: the Atherton Heritage Association, the Atherton Arts Committee, the Atherton Tree Committee, the Friends of the Atherton Community Library, the Holbrook-Palmer Park Foundation, the Atherton Dames, the Police Task Force, and the Atherton Civic Interest League. There are also home owners' associations in various neighborhoods. The Menlo Circus Club is a private club with tennis, swimming, stables and a riding ring located within the town.

There are also several tracts of contemporary Eichler homes, most notably in the Lindenwood neighborhood in the northeast part of the town.[51]

The Holbrook-Palmer Estate, was once an active rural estate and gentleman's farm.[52] The Holbrook-Palmer Estate was donated to the city of Atherton in 1958 and now serves as a 22-acre public park (8.9 ha) and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for the architecture.[52]

The city is served by the Atherton Public Library of the San Mateo County Libraries, a member of the Peninsula Library System.

Government

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Atherton is in the 13th Senate District, represented by Democrat Josh Becker, and is split between the 21st Assembly District, represented by Democrat Diane Papan and the 23rd Assembly District, represented by Democrat Marc Berman.[53] In the United States House of Representatives, Atherton is in California's 16th congressional district, represented by Democrat Anna Eshoo.[54]

Political party registration

[edit]According to the California Secretary of State, as of March 11, 2022, Atherton has 5,063 registered voters. Of those, 2,192 (43.2%) are registered Democrats, 1,247 (24.6%) are registered Republicans and 1,317 (26%) have declined to state a political party.[55]

Education

[edit]Among Atherton's public schools, Encinal, Las Lomitas, and Laurel are elementary schools, while Selby Lane is both an elementary and a middle school. Menlo-Atherton is a high school. Atherton does not have its own public school system. Selby Lane is part of the Redwood City School District, Menlo-Atherton is part of the Sequoia Union High School District, Las Lomitas Elementary School is part of the Las Lomitas Elementary School District, and both Encinal and Laurel are part of the Menlo Park City School District.

Among the town's private schools, Sacred Heart is an elementary, middle and high school, and Menlo School is a middle and high school.

Menlo College is a private four-year college.

Notable people

[edit]- Paul Allen, Microsoft co-founder.[56]

- Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Netscape and general partner at Andreessen Horowitz.[57]

- Mohamed Atalla, Egyptian-American engineer, inventor of MOSFET transistor, founder of Atalla Corporation

- Gertrude Atherton, American author

- Faxon Atherton, namesake of Atherton, California

- CiCi Bellis, tennis player

- Lindsey Buckingham, of Fleetwood Mac[58]

- Nick Clegg, Meta Platforms executive and former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and his wife, Miriam González Durántez, a lawyer[59]

- Ty Cobb, Hall of Fame Major League Baseball player

- Stephen Curry and Ayesha Curry, NBA star and actress

- Timothy C. Draper, venture capitalist and founder of Draper Fisher Jurvetson[60]

- Clay Dreslough, game designer, raised in Atherton

- Douglas Engelbart, computer engineer and inventor of the computer mouse

- Drew Fuller, actor, known for role on Charmed and Army Wives

- Bill Gurley, venture capitalist; general partner at Benchmark.[61]

- Elizabeth Holmes, former biotechnology entrepreneur convicted of fraud.[62]

- Ben Horowitz, co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz.[63]

- Ron Johnson, former senior executive at Apple

- Guy Kawasaki, venture capitalist

- Bobbie Kelsey, Stanford University women's basketball assistant coach

- Andy Kessler, author of books on business, technology, and the health field

- Jan Koum, co-founder of WhatsApp

- Robby Krieger, musician, former guitarist of The Doors

- Charlie Kubal, music producer, created 2010's Mashup Album of the Year, the notorious xx, grew up in Atherton

- Douglas Leone (born 1957), billionaire venture capitalist[64]

- Andy W. Mattes, CEO of Diebold.[65]

- Willie Mays, Hall of Fame Major League Baseball player[66]

- Bill McDermott, CEO of ServiceNow[67]

- Rajeev Motwani, professor, computer science, Stanford University[68]

- Farzad Nazem, former chief technology officer of Yahoo! and one of its longest-serving executives, now an angel investor

- Chamath Palihapitiya, CEO of Social Capital, and board member of the Golden State Warriors.

- J. B. Pritzker, Governor of Illinois and co-founder of the Pritzker Group

- Tom Proulx, co-founder of Intuit.[69]

- Vivek Ranadive, chairman, CEO and founder of TIBCO Software[70]

- Jerry Rice, Hall of Fame football player[71]

- George R. Roberts, co-founder of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts.

- Ted Robinson, sports broadcaster and former San Francisco 49ers play-by-play announcer

- Maureen Kennedy Salaman, author and proponent of alternative medicine

- James R. Scapa, co-founder, chairman and CEO of Altair Engineering

- Eric Schmidt, former executive chairman and CEO of Google[72]

- Charles R. Schwab, founder and CEO of the Charles Schwab Corporation[73]

- Komal Shah, art collector, philanthropist, and businessperson

- Shirley Temple, child movie star and diplomat

- Y.A. Tittle, 49ers & Giants QB, NFL HOFer, resident until his death in 2017

- Bob Weir, of the Grateful Dead and Ratdog, raised in Atherton[74]

- Steve Westly, former State Controller of California, major Democratic Party fundraiser, and venture capitalist.[75]

- Meg Whitman, diplomat, former president and CEO of Hewlett-Packard, former CEO of eBay[76]

- Dennis Woodside, president of Impossible Foods, former COO of Dropbox

- Quadeca, YouTuber/Rapper grew up in Atherton

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Atherton". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ a b "Atherton History". Town of Atherton. April 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "California's 16th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ "City Council". Town of Atherton. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "USPS – ZIP Code Lookup – Search By City". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "NANP Administration System". North American Numbering Plan Administration. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c Griffith, Erin (August 12, 2022). "The Summer of NIMBY in Silicon Valley's Poshest Town". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "These Are the Wealthiest Towns in the U.S." Bloomberg. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Archive of "1990 CPH-L-126. Median Family Income for Places with a Population of 2,500 to 9,999, Ranked Within the United States: 1989", United States Census Bureau. 1990 CPH-L-126F.html Original page

- ^ Levy, Francesca (September 27, 2010). "America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes". Forbes.

- ^ Brennan, Morgan (October 16, 2013). "America's Most Expensive Zip Codes In 2013: The Complete List". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

- ^ Sharf, Samantha (December 8, 2016). "Full List: America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes 2016". Forbes. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ SFGATE, Sam Moore (November 22, 2022). "Bay Area town named most expensive ZIP code for 6th year". SFGATE.

- ^ Kolomatsky, Michael (November 9, 2023). "America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "History of Atherton, California".

- ^ "Atherton Wealthy Will Still Maybe Try To Block High-Speed Rail". SFist - San Francisco News. July 11, 2016. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (February 10, 2015). "Atherton, high-speed rail foes sue to block electrifying Caltrain". SFGATE. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (July 25, 2004). "End of an Era / Caltrain's electrification plans threaten Atherton's railroad charm". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (February 10, 2015). "Atherton, high-speed rail foes sue to block electrifying Caltrain". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Orr, John (July 8, 2015). "Atherton lawsuit against Caltrain over electrification project clears one hurdle". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Orr, John (July 11, 2016). "Atherton won't seek temporary injunction in fight with Caltrain". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Weigel, Samantha (September 27, 2016). "Judge gives Caltrain electrification green light: Atherton loses lawsuit, claims local project was too closely tied to high-speed rail". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Wood, Barbara (September 28, 2016). "Atherton loses lawsuit over Caltrain electrification project". The Almanac. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Weigel, Samantha (December 15, 2016). "Caltrain supporters unfazed by high-speed rail suit: Officials believe bond sale, electrification will stay on track despite new case". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ "An act to add Section 2704.78 to the Streets and Highways Code, relating to transportation". California Office of Legislative Counsel. September 28, 2016.

- ^ Swartz, Angela. "Atherton signs off on Caltrain proposal to permanently close its train station". www.almanacnews.com. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Proposed Closure of Atherton Caltrain Station". www.caltrain.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Locke, Taylor. "These are the top 10 richest places in America". CNBC. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Pender, Kathleen (July 27, 2019). "Here's how Atherton became the Bay Area's most expensive city for housing — by far". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Ho, Vivian (December 6, 2020). "'Flexing their power': how America's richest zip code stays exclusive". The Guardian. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Priscilla Yuki (February 12, 2019). "Why are there no sidewalks in Atherton/Menlo Park?". KALW. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Atherton CA Home Prices & Home Values". Zillow. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Swartz, Angela (January 27, 2023). "Steph and Ayesha Curry oppose upzoning of Atherton property near their home". www.almanacnews.com. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Swartz, Angela. "Atherton: SB 9 applications start to trickle in". www.almanacnews.com.

- ^ a b Demsas, Jerusalem (August 5, 2022). "The Billionaire's Dilemma". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Varian, Ethan (October 9, 2022). "Bay Area cities running out of time to convince the state they can build 441,000 new homes". The Mercury News. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Toledo, Aldo (August 19, 2022). "One in 10 Bay Area neighborhoods is 'highly segregated' enclave of White wealth, new report says". The Mercury News. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ "Multifamily housing near Steph Curry's Atherton home gets approval". KTVU FOX 2. February 2, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ "Town of Atherton General Plan" (PDF). Neal Martin & Associates. November 20, 2002. pp. LU–1. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Atherton town, California". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Atherton town". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Highest Income Per Household In The United States By City". Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ Levy, Francesca (September 27, 2010). "America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes". Forbes.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Atherton town, California". United States Census. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. United States Census. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Brenda. "The 10 Most Expensive Zip Codes For Buying A Home". Forbes. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Most Expensive U.S. Zip Codes: 2022 Shatters Last Year's Records with 14 Zip Codes Surpassing $4 Million Median". PropertyShark Real Estate Blog. November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ "Lindenwood Eichler". Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. September 26, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "California's 18th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "Report of Registration" (PDF). California Secretary of State. March 11, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Meisenzahl, Mary. "A Microsoft cofounder's $35 million mansion in the most expensive town in the US just sold — see inside". Business Insider. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Robinson, Melia. "We scouted the homes of the top tech executives, and they all live in this San Francisco suburb for the 1%". Business Insider. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Lindsay Buckingham with Special Guest Stevie Nicks". Soundstage. HD Ready, LLC and WTTW. 2005. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ Lumley, Sarah (January 26, 2019). "Nick Clegg swaps Putney townhouse for £7million California mansion ahead of new Facebook role". Telegraph. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Palmeri, Christopher; Linda Himelstein (November 6, 2000). "Tim Draper's Voucher Crusade". BusinessWeek. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Swartz, Angela (November 6, 2019). "Atherton: Uber drivers, other contract workers protest outside of Uber investor's home". Mountain View Voice. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ "Holmes and Balwani Created LLC to Buy $9 Million Silicon Valley House". WSJ. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Helft, Miguel (February 27, 2014). "Silicon Valley's stealth power". Fortune. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forbes profile: Douglas Leone". Forbes. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ Cho, Janet H. (June 7, 2013). "New Diebold CEO Andy W. Mattes plans to be direct and ask lots of questions as he steers the company back on track". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

He has also worked in China and Brazil, and now lives in Atherton, Calif.

- ^ Taylor, Phil (July 14, 2008). "Willie Mays". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Shah, Oliver (August 12, 2023). "Bill McDermott: Losing my sight felt like destiny — vision is not just about what you see". The Sunday Times.

- ^ AP Associated Press (June 8, 2009). "Stanford computer prof. Rajeev Motwani found dead". SFGate. Hearst Communications Inc. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Cortese, Amy (August 7, 1997). "My Jet Is Bigger Than Your Jet". BusinessWeek. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "The Buzz – the week that was". SFGate. Hearst Communications Inc. June 21, 2009. pp. K–1 of the San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ The Associated Press (June 6, 2001). "Jerry Rice becomes newest Oakland Raider". The Berkeley Daily Planet. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Dolan, Kerry A. (n.d.). "World's Billionaires List: The Richest in 2021". Forbes. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "#58 Charles R Schwab". The 400 Richest Americans. Forbes. 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ McNally, Dennis (2002). A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-1185-6.

- ^ "Google staffers quiz candidate Obama". USA Today. USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co. Inc. November 15, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ "The Ripon Profile — Meg Whitman of California, Former CEO of eBay Inc". The Ripon Forum. November–December 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2009.